Love sandalwood? It’s facing extinction. Here’s why.

The iconic outback tree is still being harvested in the wild in Western Australia where it’s considered a “forest product”, all to satisfy incense-burners and perfumeries.

Our research, published today, reveals the WA government has known for more than a century that sandalwood is over-harvested and is declining in numbers, with no new trees regenerating. We estimate 175 years of commercial harvesting may have decreased the population of wild sandalwood by as much as 90%.

Today, walking into most sandalwood communities is like walking into a palliative care hospice. There are only old folk there, most of them in terminal decline. There are no youngsters and there are certainly no babies.

It’s time to list sandalwood as a threatened species nationally, and start harvesting only from plantations to give these wild, centuries-old trees a fighting chance at survival.

The tree behind the fragrance

Australian sandalwood, one of about 15 different species of sandalwood that grows across Oceania, is a highly valued economic resource as one of the main types of sandalwood traded internationally. But it’s also immensely important ecologically and culturally.

Aboriginal people have revered it for thousands of years, using it, for example, in smoking ceremonies and bush medicine. These uses take only small portions of the tree and do not endanger the plant, compared to commercial harvesting which kills the tree.

Ecologically, it’s a keystone resource in the arid outback, often flowering and fruiting when other plants are not. It attaches its roots to host plants such as acacias, enabling it to derive some of its nutrients and water from nearby trees and shrubs.

Sandalwood trees can live an estimated 250–300 years, and are capable of withstanding extremely harsh conditions. And yet, the species is extremely fragile in the first few years after germination.

Sandalwood populations have been slowly collapsing for decades from commercial harvesting, land clearing, fire, and grazing (by introduced herbivores such as goats, sheep, cows, rabbits, and camels, and some native species such as kangaroos).

The biggest problems are its lack of regeneration and the rapidly changing climate. Studies suggest there have been virtually no new trees emerging in most sandalwood populations for 60–100 years.

There are two main reasons for this. First, sandalwood has lost its seed dispersers, such as burrowing bettongs (small marsupials), which went extinct across most of their range about the same time sandalwood stopped recruiting.

Second, climate change. Sandalwood seeds will only germinate, establish, and survive as seedlings if they get three consecutive good years of rainfall. Under Australia’s increasingly variable rainfall conditions, that’s rarely happening.

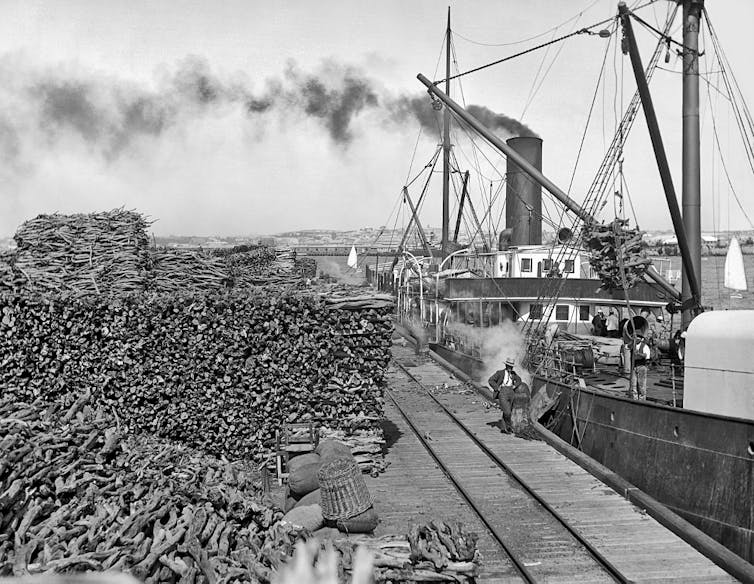

Wooden gold

Sandalwood is one of the most expensive timbers traded in Australia, making it “wooden gold” for the WA government’s forestry department, the Forest Products Commission.

The oil from this native plant is used in perfumes, soap, and moisturisers, and the heartwood “goes up in smoke” as incense in temples and homes, particularly throughout Asia.

The WA government currently harvests old-growth sandalwood trees almost exclusively from the wild, where the oldest trees have the best oil quality. Plantations do exist, but they are not yet being fully utilised to replace wild-sourced timber.

Our research delved into more than 100 scientific papers, unpublished theses, parliamentary reports and historical documents, and found scientists have repeatedly warned the WA government of the tree’s dire situation.

For example, a century ago (in 1921), in a report to the head of the WA Forests Department, Charles Lane-Poole, Forests Department official Geoffrey Drake-Brockman expressed fears sandalwood harvesting was sending the species extinct in the wild. He recommended the industry start harvesting from plantations instead, writing:

The State Government’s profit (from better managed harvesting) would enable the Forests Department to establish large plantations of sandalwood so that when the natural supplies cut out, the plantations would supply the market requirements.

Years later, in 1958, another report for the WA Forests Department warned:

The sandalwood tree is approaching extinction. The story of the geographical movement of the (sandalwood) industry across WA is the story of the rise and decline of the industry. All too commonly extinction followed exploitation.

Early in the industry’s history, fears were expressed as to the possibility of the future exhaustion of supplies of sandalwood […] Today, the sandalwood tree is approaching extinction […] Little hope of conservation and regeneration remains.

These are just two of scores of examples of warnings documented in our research, all of which have been ignored by successive WA governments. Scientists and others are still putting these same recommendations to the WA government.

It’s not too late to save it

Fortunately, sandalwood will not completely disappear as there are thousands of hectares of sandalwood in plantations in WA’s agricultural zone. The industry should urgently transition to only harvest from plantations, taking over-harvesting pressure off wild populations.

We urge the WA government to make that transition. The government must list sandalwood as an endangered species now (as it is in South Australia), before it declines to extinction in the wild, and protect and restore surviving populations in innovative programs with Aboriginal rangers and Traditional Owners.

And we urge you, the consumer, to find out more about any sandalwood you purchase.

Plantation-grown products are readily available and just as sweet smelling. Your support will help the industry transition away from wild-harvested plants that need all the help they can get.

Richard McLellan, PhD candidate, Charles Sturt University; David M Watson, Professor in Ecology, Charles Sturt University, and Kingsley Dixon, John Curtin Distinguished Professor, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.