World first: Muddied mummy reveals new details of ancient practice

A world-first discovery at Macquarie University published today challenges what we know about ancient Egyptian mummification and raises questions about mummified bodies held in collections worldwide.

A team led by Dr Karin Sowada, a research fellow at Macquarie’s Department of History and Archaeology, examined the layers encasing a mummified adult woman kept at the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney, using advanced CT scans (computed tomography).

3D visualisation and cross-sectional scans revealed a carapace, or shell, encasing the body made from mud and straw sandwiched between layers of linen. Typically, this shell is made from resin, an imported material at the time.

“Mummified bodies in collections all over the world have been sitting right under our noses for generations. The application of new technology can reveal totally new information which challenges what we previously knew,” Sowada says.

The family likely organised a mud carapace as a form of ancient conservation to assist her transition to the hereafter.

Mummification is the process used to preserve the dead by drying and embalming, practiced widely in many ancient cultures. Archaeologists had not recorded the use of mud carapaces within layers of textile wrappings as a technique in Egyptian mummification before now.

Sowada was involved in conducting initial scans on the mummified body in 1999 during which the carapace was first discovered. Nearly two decades later, working with radiologist Professor John Magnussen, bio-archaeologist Professor Ronika Power and the museum’s senior curator Dr James Fraser who initiated the project, she analysed new CT scans.

“The technology has improved enormously for medical purposes. And so the new visualisations of the wrapped body are incredibly good, many times better, than in the late ‘90s,” she says. “We can see so much more detail.”

In a CT scan, radiologists use computerised X-ray imaging creating a narrow beam of X-rays around the body or object to produce cross-sectional images. Improved computing enhances analysis of scans, enabling better visualisation of what lies beneath the wrappings.

Conservation or imitation?

Dr Timothy Murphy, a geochemist at Macquarie, helped determine that the carapace consisted of a thin base layer of mud, coated with a white calcite-based pigment and a red-painted surface of mixed composition.

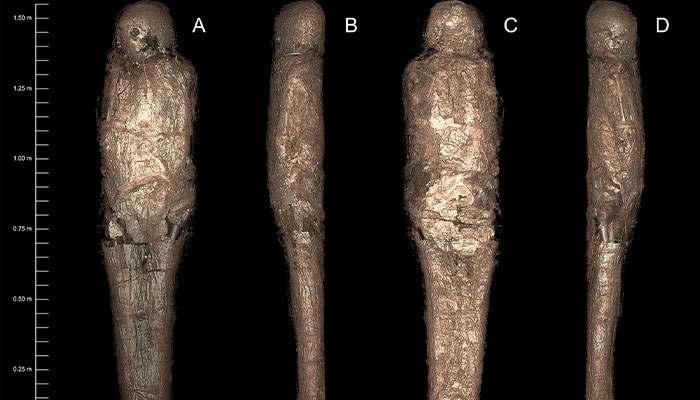

In the detail: 3D-rendered CT images of the mummified adult woman. 21st-century medical technology allows ‘incredibly good’ visualisations. Photo credit: Chau Chak Wing Museum and Macquarie Medical Imaging.

Previously, researchers had discovered resinous paste and linen shells within mummy wrappings through autopsies and radiological imaging. Yet such shells are little studied and usually assumed to be made of resin, based on comparison with bodies of the Egyptian elite.

Ancient Egyptians believed that mummification helped transition the deceased from death to the afterlife and rebirth, Sowada says. “Some of the bones had separated from each other, damage probably caused by ancient tomb-robbers. The family likely organised a mud carapace as a form of ancient conservation to assist her transition to the hereafter.”

Another hypothesis is that the mud carapace is an example of ‘elite emulation’. The deceased’s family may not have been able to afford the expensive resin which was used by Egyptian elite classes and imported from the Mediterranean coast, so they used cheaper, readily available mud – probably from the nearby Nile.

“Even today, when the rich and famous decide to do something it often sparks a fashion trend that percolates down to the rest of society who try to copy it,” Sowada says.

The mystery mummy

The research team also partnered with Dr Geraldine Jacobsen and her team at ANSTO (Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation) to radiocarbon date the linen wrappings. The ANSTO team discovered the wrappings date to the 12th century BC, around 3200 years ago. This led to another puzzling discovery.

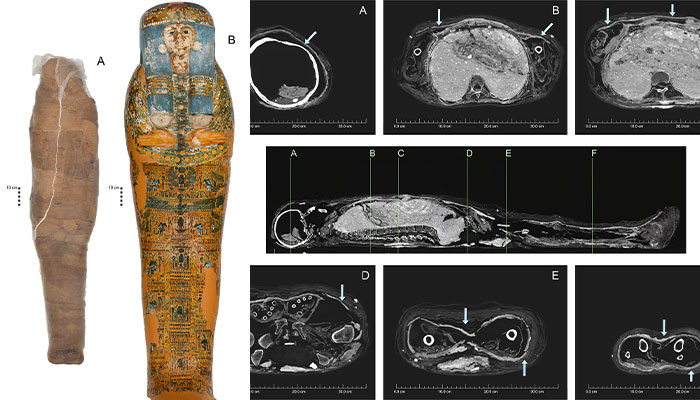

New views: The mummified woman, encased in a modern sleeve for conservation, and its coffin (left) and CT images showing transverse views of the carapace at different locations. Photo credit: Chau Chak Wing Museum and Macquarie Medical Imaging

“Carbon dating revealed a discrepancy of 150-200 years between the date of the mummified person and its coffin,” Sowada says. “Based on the decorative style, the coffin dates to about 1000 BC. The results indicate that the body is older than the coffin and does not belong to it.

The inscription on the wooden coffin names the original occupant as the lady Meruah, ‘Mistress of the House’, ‘Chantress of Amun’ and ‘Adorant of Mut in Isheru’. Mut was the consort of the god Amun and Isheru is the ancient name given to part of her temple at the Karnak complex in ancient Thebes.

Sowada says these titles suggest the original person in the coffin was a married woman of relatively high status.

The coffin and the associated body were part of a collection by philanthropist and politician, Sir Charles Nicholson, who donated it to the University of Sydney in 1860 after he bought it during a trip to Egypt a few years earlier.

“Perhaps, the dealer who sold it to Nicholson just rustled up a mummified body from another source to fill the empty coffin. The dealer probably thought a tourist wasn’t going to know the difference,” Sowada says.

Dr Karin Sowada (pictured with Candace Richards, Acting Curator of the Nicholson Collection) is a specialist in the archaeology of Egypt and the Middle East, and Research Fellow in the Department of History and Achaeology.

For more exciting archaeological discoveries, see Issue 161 of Australian Geographic, on sale 25 February 2021.