Saving the endangered heath mouse, one burn at a time

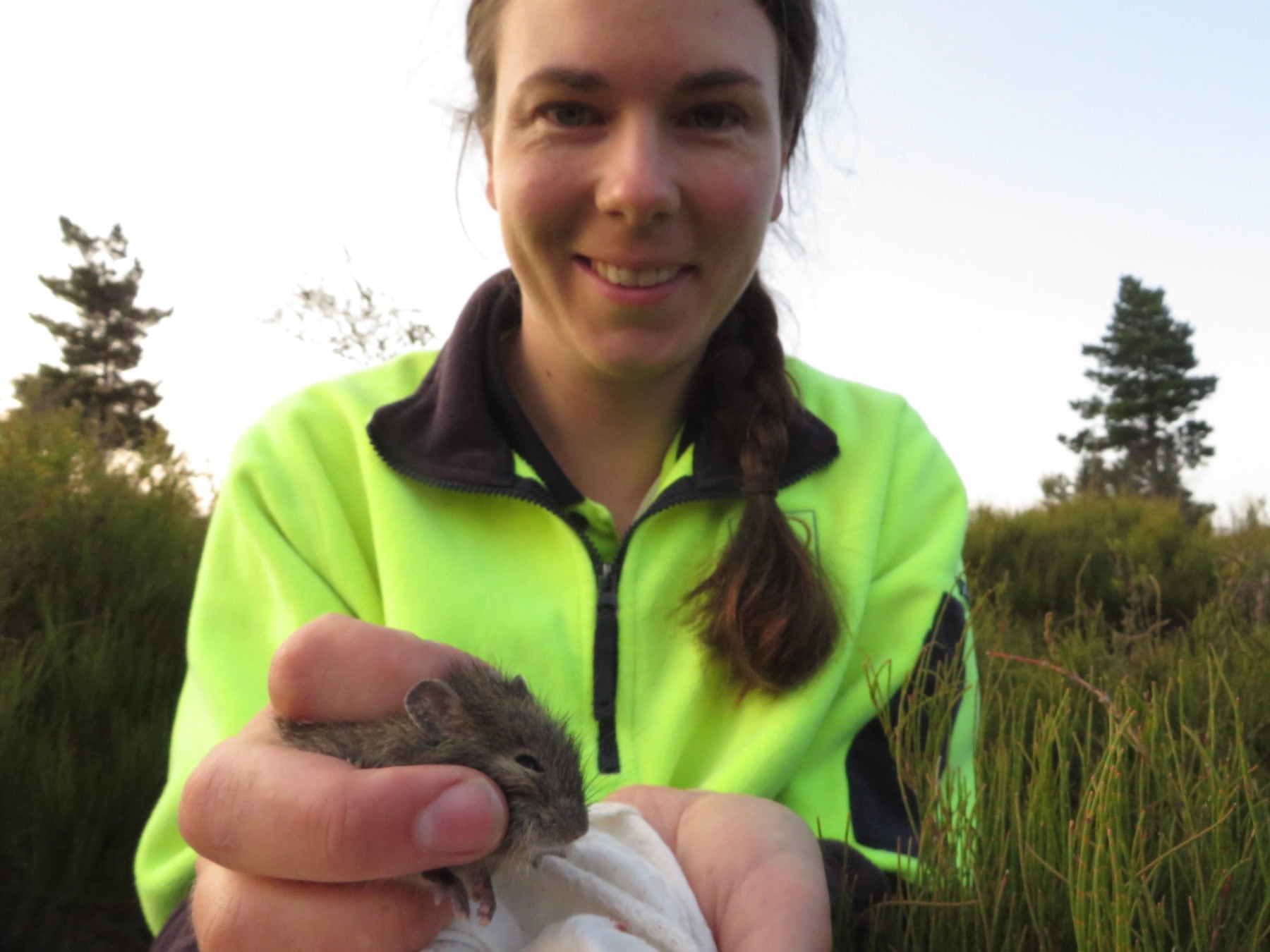

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, meet the dayang (Pseudomys shortridgei) – heath dweller, flower feaster and day napper. At a petite 9.5-12cm, this long-whiskered lovely is a member of the Old World rat family, which will no doubt send shivers down the spine of musophobes! But fear not rat haters, this bobble-eyed, endangered heath mouse is at the cutting edge of scientific research into the link between fire and native species’ survival.

As we all know, bushfires in Australia not only threaten human life and property, but cause significant changes to ecosystems. Increasingly, prescribed fire regimes are used to reduce dry fuel load as well as lower the intensity and spread of fires.

Along with affecting wildlife populations directly, bushfires can also affect animals indirectly by changing the surrounding vegetation. This influences where habitat is available and how animals will respond to fire-induced changes depending on their habitat requirements.

The heath mouse lives in patches of treeless heath surrounded by woodland. Occurring in two geographically remote areas in south-western Western Australia and around the southern border of South Australia and Victoria, it’s sensitive to the effects of fire regimes on the small amount of available habitat left.

Scientists at the Fire Ecology and Biodiversity Lab at the University of Melbourne are mapping the DNA of heath mouse populations to discover how fire regimes affect their movement.

“We hope to find out whether fire helps or hinders movement among these islands of treeless heath by catching the animals and taking DNA samples,” says Dr Holly Sitters, coordinator of the Fire and Fragmentation Project.

“The ability of animals to disperse and breed is critical to the survival of populations under changing environmental conditions. By relating genetic information to fire history and other aspects of landscape structure, we’ll be able to help fire managers decide where and when to apply fire to promote population persistence in the long term.”

Like any animal, heath mice require a minimum habitat area to meet their needs for food, shelter and breeding.

Current ecological approaches to fire management involve the use of fire mosaics, however this presents several problems when it comes to preserving biodiversity; the effect of fire on how they move through their habitat and the significance of fire on their ability to find other mice to have sex with, a vital part of population survival.

Their ability to connect affects genetic diversity, which is the basis of population health.

“Currently, fire simulation is normally applied in the context of hazard reduction rather than biodiversity conservation, but there’s huge potential to use fire simulation in wildlife management,” says Holly.

There is a capacity to use fire to influence wildlife movement patterns for the benefit of genetic diversity and the species survival such as the heath mouse, as well as the surrounding ecosystems. Holly says a shift in the focus of ecological fire management to consider functional connectivity (the connectivity between brain regions that share functional properties) could result in better conservation outcomes for all species facing a changing climate.

“Genes are at the foundation of ecological function, and genetic diversity in populations is linked to ecosystem resilience, the capacity to adjust to environmental disturbances such as fire or drought,” she says.

Holly and her colleagues are leading a small army of students and volunteers to collect data on a variety of small lizard and bat species, as well as southern brown bandicoots and even a marsupial mouse, the yellow-footed antechinus.

They’re hoping to use the genetic data they collect to map functional connectivity and assist fire managers to refine methods for promotion of long-term species persistence.

“The combined use of fire simulation and empirical data could help us decide where and when to use prescribed fire for the benefit of wildlife populations at the scale of both fire events and fire regimes.”

Lucy Smith holds a Master of Environmental Science, specialising in forest community ecology. Her interests span a range of ecological areas, including natural asset management in agriculture and the interaction between humans and wildlife.