Centipede venom as strong as its pincers

IN THE WORLD OF venomous animals the general rule is: the weaker your physical attributes, the more you need to compensate with the potency of your venom. But new research into centipede venom may upend this theory.

Centipedes belonging to the group scolopendromorpha have large sickle-shaped pincers, called ‘forcipules’, with a blade-like inner edge they use to inject the venom. Following the general rule, it would be expected they’d have simpler, less potent venom, but this is not the case, as Australian researchers have found.

These centipedes have the best of both worlds, producing a venom potent enough to kill large prey such as mice and lizards. Likewise, scutigeromorpha centipedes, which have slender and delicate forcipules, have relatively weak venom.

The difference in centipedes comes down to the complexity of their venom glands, says lead researcher Dr Eivind Undheim from the University of Queensland.

“Scolopendrids are unique amongst centipedes for having complex venom glands with many venom-producing structures,” he says.

The powerful claws, or ‘forcipules’, of Scolopendra moristans combined with their potent venom make them formidable predators. (Credit: Eivind Undheim)

Venom production based on complex venom glands

Typically, the more unique compounds an animal can make, the more complex the mixture and the more powerful their venom will be. Some of the most powerful venoms can contain several thousand unique compounds.

When examining the microscopic structure of the venom glands the researchers found the physically stronger scolopendromorphs can have up to 100 times as many venom-secreting cells as the weaker scutigeromorphs. Using mass spectrometry techniques, they also found that different areas of the venom gland appear to produce different types of chemical compounds at different concentrations.

“One possible explanation is that they have a much wider spectrum of prey items and need a greater variety of toxins to handle this,” says Eivind.

The less formidable scutigeromorphs may capture their prey using a different ‘venom strategy’, says Eivind. They may require less complex toxins if they eat a smaller variety of prey or only need to use venom for prey capture and not for defence.

Edited by Carolyn Barry

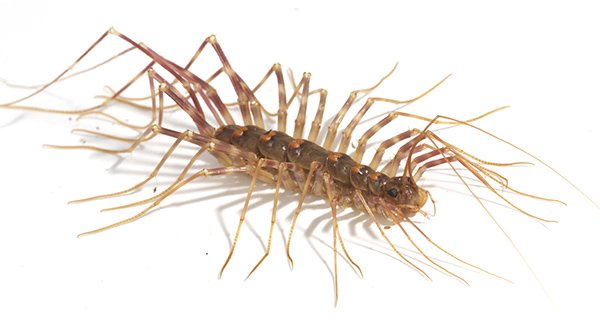

Species such as Thereuopoda longicornis have more delicate forcipules and less potent venom. Despite this they are still successful predators. (Credit: Eivind Undheim)