Species loss almost twice as slow as thought

THE PACE AT WHICH humans are driving animal and plant species toward extinction through habitat destruction is at least twice as slow as previously thought, according to a study released on Wednesday.

Earth’s biodiversity continues to dwindle due to deforestation, climate change, over-exploitation and chemical runoff into rivers and oceans, said the study, published in the presitgious journal Nature.

“The evidence is in – humans really are causing extreme extinction rates,” said co-author Stephen Hubbell, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California at Los Angeles.

But key measures of species loss in the 2005 UN Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report are based on “fundamentally flawed” methods that exaggerate the threat of extinction, the researchers said.

Changes in the extinction rates of endangered species

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of endangered species – likewise a benchmark for policy makers – is now also subject to review, they said.

“Based on a mathematical proof and empirical data, we show that previous estimates should be divided roughly by 2.5,” Hubbell told journalists by phone. “This is welcome news in that we have bought a little time for saving species. But it is unwelcome news because we have to redo a whole lot of research that was done incorrectly.”

Up until now, scientists have asserted that species are currently dying out at 100 to 1000 times the so-called ‘background rate’, the average pace of extinctions over the history of life on Earth. UN reports have predicted these rates will accelerate tenfold in the coming centuries.

The new study challenges these estimates. “The method has got to be revised,” said Hubbell. “It is not right.”

Such apparent inaccuracies in the figures have arisen because it is difficult to directly measure extinction rates. Preivoulsy, scientists used an indirect approach called a ‘species-area relationship’. This method starts with the number of species found in a given area and then estimates how that number grows as the area expands.

To figure out how many species will remain when the amount of land decreases due to habitat loss, researchers simply reversed the calculations.

But the study, co-authored by Fangliang He of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, shows that the area required to remove and entire population is always larger – usually much larger – than the area needed by a species when it first enters a habitat.

“You can’t just turn it around to calculate how many species should be left when the area is reduced,” said Hubbell. That, however, is precisely what scientists have done for nearly three decades, giving rise to a glaring discrepancy between what models predicted and what was observed on the ground or in the sea.

Extincion forecasts dispelled

Dire forecasts in the early 1980s predicted that as many as half of species on Earth would disappear by 2000. “Obviously that didn’t happen,” Hubbell said. But rather than question the methods, scientists developed a concept called ‘extinction debt’ to explain the gap.

Species in decline, according to this logic, are doomed to disappear even if it takes decades or longer for the last individuals to die out. But extinction debt, it turns out, almost certainly does not exist.

“It is kind of shocking” that no-one spotted the error earlier, said Hubbell. “What this shows is that many scientists can be led away from the right answer by thinking about the problem in the wrong way.”

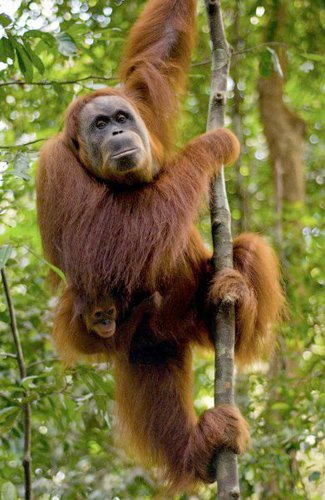

Human encroachment is the main driver of species extinction. Only 20 per cent of forests are still in a wild state, and nearly 40 per cent of the planet’s ice-free land is now given over to agriculture. Some three-quarters of all species are thought to live in rain forests, which are disappearing at the rate of about half-a-per cent per year.

RELATED STORIES