Astronomers study the sound of stars

A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY of the vibrations – or ‘starquakes’ – of thousands of distant stars is giving astronomers new insight into how stars work.

A team of scientists from Australia, Europe and the US, this week presents the results of a study using NASA’s space-based Kepler telescope which looks in detail at the way stars vibrate.

The Kepler mission has “revolutionised” the study of star interiors, according to lead author on one of the studies, graduate student Daniel Huber from the University of Sydney. “It’s like playing in a giant sandbox – there is so much more data than we had even four to five years ago,” he told Australian Geographic.

Starquakes

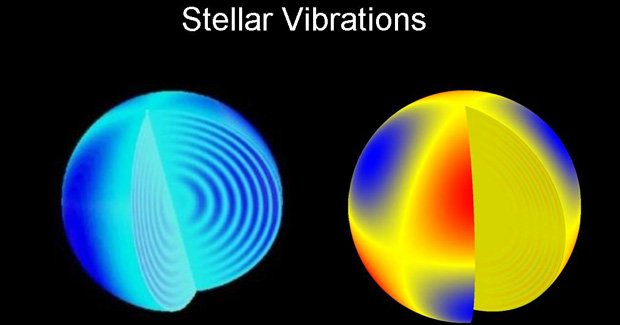

Stars are giant balls of gas with hot, turbulent interiors. This turbulent motion makes a star oscillate or vibrate and also causes it to grow and shrink in size, temperature and brightness. Studying the way the oscillations travel through them provides clues to the stars’ sizes, ages and structures, much like earthquakes travelling through the Earth can reveal the layered structure of the planet’s interior.

“Because we have stars of so many different types, we can compare them to theories of how stars form in our galaxy,” says Daniel. “It shows us our theoretical picture of the Milky Way is accurate.”

The vibrations also create a low-pitched sound, which Daniel has sped up one million times, creating a spooky soundfile and bringing the oscillations within the range of human hearing. Listen to it here.

Unlike a musical instrument, stars resonate with several frequencies at once. The audio file was created by taking the frequencies of one star’s oscillations (in light) as observed by Kepler over a short period. These frequencies were synthesised on a computer and sped up by one million times. The audio file is actually one star being joined by a second, a third, and a fourth with a new star coming in every 15 seconds.

Vital signs of stars

The Kepler mission was launched in March 2009, to search for planets around roughly 150,000 stars. “We’re essentially taking the vital signs of these stars, measuring their size, structure, and age, using methods that will also be useful for planet-hosting stars,” says astronomer Jorgen Christensen-Dalsgaard, from Aarhus University, Denmark, who leads the research into the stars’ structure.

Australian co-author and astrophysicist Tim Bedding, also from the University of Sydney, is taking part in the study of a Sun-like star, KIC 11026764, nicknamed ‘Gemma’, which is one billion years older than our own Sun. Being larger, Gemma resonates with a deeper sound, much like a cello sounds deeper than a violin.

He and Daniel also looked at thousands of giant stars that represent the eventual fate of our own Sun. The study confirmed our Sun’s fate is sealed in about six billion years when it will gradually swell to become a giant star, ultimately stretching out close to Earth’s current orbit.

“It doesn’t matter to us, though, we’ll be dead,” says Tim. “It’s a matter of knowing how stars work – we understand the sun pretty well, but the more we observe other stars the better we can understand our own Sun.”

MORE INFO

Read more AG stories about Australian astronomy

NASA’s Kepler mission