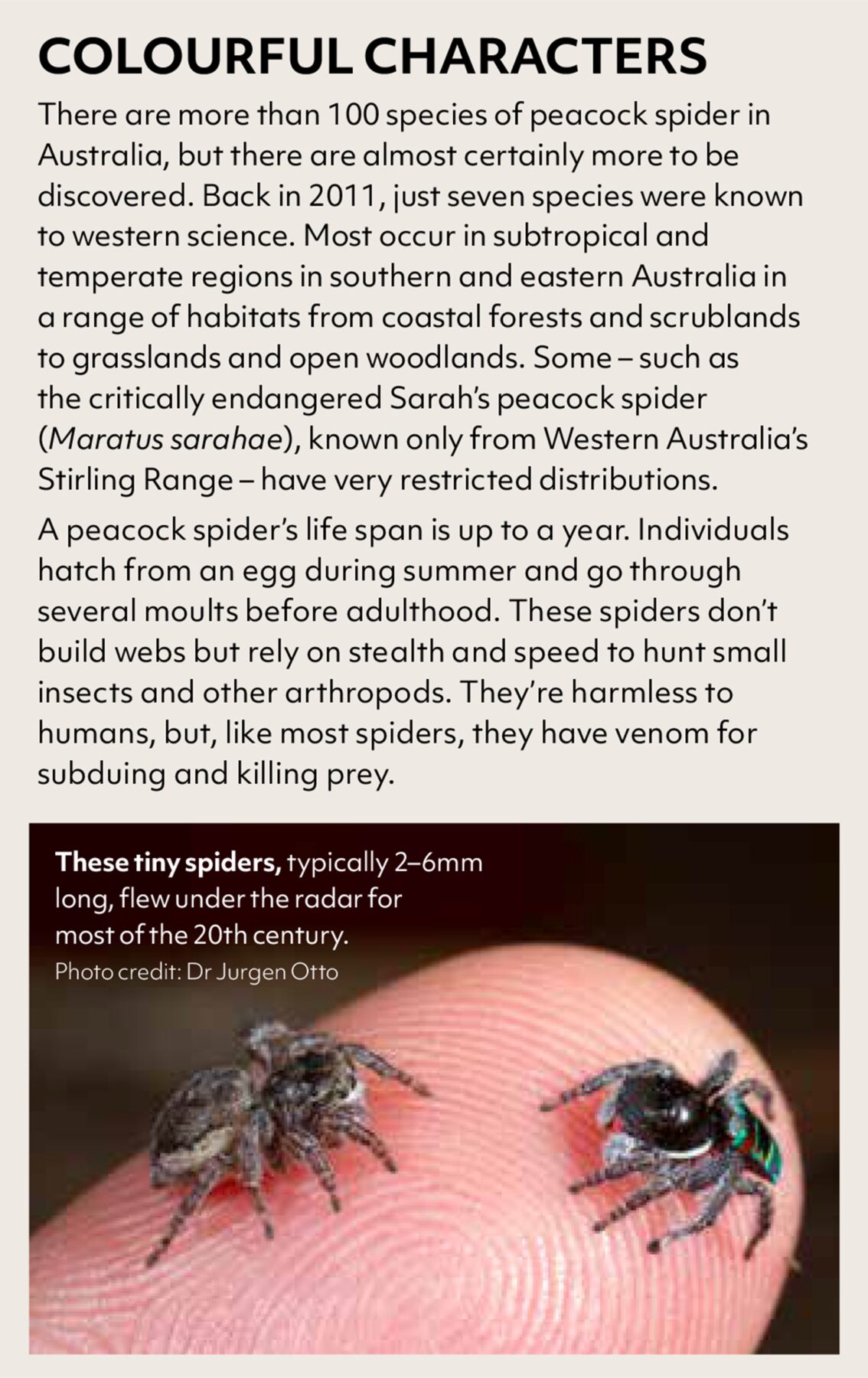

When Sydney-based biologist Dr Jurgen Otto became the first person to photograph a Maratus volans peacock spider’s courtship display in 2008, he couldn’t have known these tiny arachnids would one day become the darlings of the internet.

Jurgen first became fascinated with these remarkable spiders in 2005 after a chance encounter with one in bushland near Sydney. At the time, not much was known about these elusive jumping spiders; no one had observed the males’ courtship displays, and females were still unknown to science. But Jurgen’s once-amateur interest quickly snowballed into his life’s passion.

He has since published scientific papers, described new species, and even introduced them to world-renowned naturalist Sir David Attenborough. Today, his photographs and videos of male peacock spiders have taken social media by storm, racking up millions of views for their dazzling, iridescent colours and bewitching ‘dance’ moves.

His most-viewed YouTube video has more than 9 million hits. In the video, a male coastal peacock spider (Maratus speciosus) performs an elaborate courtship display, his emoji-faced abdomen held aloft as he waves his third legs in time to techno music. Watch this stunning spider dance, and you can’t help but smile:

At Macquarie University’s School of Natural Sciences, master’s student Anna Seibel and her research supervisor, Associate Professor Ajay Narendra, are smiling too. Their high-speed camera reveals that, as well as having good looks and sharp moves, peacock spiders also hold their own in nature’s Olympics.

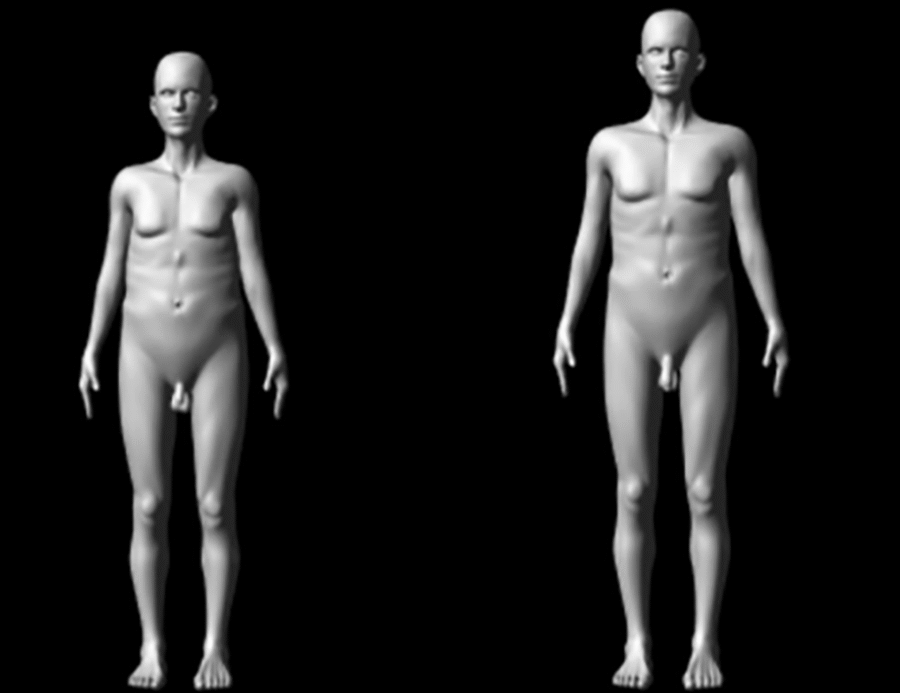

Humans – with the notable exception of Marvel’s Spider-Man – cannot compete with peacock spiders. Anna and Ajay have clocked the jumping acceleration of splendid peacock spiders (Maratus splendens) at a breathtaking 127m per second squared. In comparison, Usain Bolt’s burst out of the blocks in his world record-breaking 100m sprint was a mere 9.5m/s².

As members of the Salticidae family (the jumping spiders), peacock spiders have it over us in the long jump too. Jumping spiders leap prodigious distances – often 10–15 times their body length. The 8.95m long jump world record, set in 1991 by US athlete Mike Powell, was an impressive leap of more than four times his own height. But if your average 1.75m Aussie bloke could leap like a jumping spider, he could travel across his street and into his neighbour’s yard in a single bound. And if you can manage that, we’ll see you in Brisbane in 2032!

Spider athletics

It’s one thing to clock human athletic records, but how do you measure motion in a tiny peacock spider? And how do you even get them to jump? Anna and Ajay have that sussed.

“We 3D-printed take-off and landing platforms that were 4cm apart,” Anna explains. “Then we gently placed the spiders on the take-off platform and waited anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes for them to leap over the gap. Sometimes they needed a little nudge to move.”

Once a spider launched, fancy camera gear came into play. “Because the spiders jump so incredibly fast, we film them with [a] high-speed camera,” Anna says. “It’s like watching a slow-motion video.”

The researchers attached a high-performance macro lens to their Phantom T1340 to catch the action at 5000 frames per second – about 160 times faster than the human eye can register. “The spider moves very fast during the jump, so we really need to freeze every little bit of movement,” Ajay says.

Then Anna and Ajay track the spider’s body parts to chart its jump. “They have four pairs of legs, and we have to track every single leg joint, and [also track] the spider’s centre of gravity,” Ajay says. Frame by painstaking frame, a spider’s jump, which happens in an instant, takes the researchers a few hours to work through.

But it’s worth the effort. “We use that to characterise what they’re doing throughout the jump; for example, the way in which the legs are extended can tell us about which legs are the propulsive pair,” Anna says.

The way spiders move their legs to jump isn’t the same way we do it. Mike Powell, Olympic hopefuls, kids using skipping-ropes in the school playground – we all use our muscles to power our leaps. Spiders aren’t equipped for that. “They do have flexor muscles, so they can bend their legs,” Ajay says. “But they don’t have muscles to extend their legs. To do that, they use fluid.”

Like most arthropods, spiders are filled with a blood-like fluid called haemolymph. When a spider wants to jump, it pumps this fluid down into the legs. “That straightens the legs out, which launches the spider into the air,” Ajay explains. “Because they use hydraulic pressure, their jumps tend to be much faster than muscle-driven jumps.”

“It’s amazing,” Anna says, “to think how these tiny animals, just 2–6mm in body length and weighing about 2mg, generate enough force, and enough acceleration, to actually jump like this.”

Why do peacock spiders jump? And why so speedily? Anna says there are several reasons. “One of the main reasons is to catch prey. They catch fast-moving prey like flies, ants and planthoppers, so being able to jump quickly is important,” she says. “It also gives them an efficient way to move through the environment. For example, when crossing a gap, it’s a lot faster and more efficient to jump across than to take a long detour by walking. They also, of course, jump to escape predators.”

That predator could be a mate. “Male peacock spiders have to make a hasty retreat as soon as they finish courting, because the females are cannibalistic. They’ll eat the male once they finish mating,” Ajay says.

Like almost all the jumping spiders that have been studied so far, splendid peacock spiders use their third pair of legs to power their jumps. With such high stakes, the splendid peacock spider’s mating display is therefore surprising. Because, as the millions of YouTube viewers know, jumping isn’t all that peacock spiders use their legs for. Males also wave their legs during courtship.

“They get the common name ‘peacock spider’ because, just like peacocks, the males display and dance to females during courtship,” Ajay says. “What we see in splendid peacock spiders is that, as well as for jumping, they also use their third pair of legs in courtship display. This may be the norm in all the peacock spiders, but at this stage, we don’t know.”

This multitasking must be challenging for a male splendid peacock spider. “He needs to display to attract the female, but if he needs to make a rapid escape, he has to rely on the same legs, which means he’s going to lose time,” Ajay says. “He has to stop waving, put his legs down, and then jump fast – because the female can jump and catch him.”

Splendid peacock spider females are much larger than males of the species. They weigh a hefty 10mg on average, while the tiny males can weigh as little as 5mg. But those extra reserves that are needed for egg production mean females aren’t quite as quick on the take-off as their suitors. Speed is on the male’s side.

Nevertheless, as Spanish racewalker Laura Garcia-Caro learned at the 2024 European Athletics Championships, trying to move fast and wave at the same time can see you overtaken. “They’ve put all their eggs in one basket in terms of these two rather critical things they have to do,” Ajay says of the splendid peacock spider’s third pair of legs.

But more research is needed to understand the evolutionary trade-offs. “It could be that they’ve invested heavily into one pair that [is] longer, thicker and heavier, and can generate more power that allows for better jumps,” Ajay says. “With tufts of hair, their third pair of legs also [has] a much larger surface area to use as a reliable signal when courting the female.”

There’s still much to learn about the jumping power of peacock spiders and their relatives. “All we’ve done at this stage is look at locomotion,” Ajay says of the controlled jumps the researchers have observed in the lab. In the wild, however, jumping spiders live in all sorts of cluttered habitats where they leap for all sorts of reasons. Escape jumps, or jumps that spiders make when they’re startled, are likely to be much less directed – and probably even faster, as Anna, Ajay and their colleagues proposed recently in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

And then there’s endurance. In the lab, Anna and Ajay studied single jumps, but jumping spiders often jump multiple times in a row. Whether leaping their way through the arachnid equivalent of a marathon alters the mechanics of individual jumps is unknown, and how peacock spiders would fare in the triple jump event is yet to be determined. But they’d probably make the 400m hurdles on an Olympic track look like a Sunday stroll.

Watch this space. Besides the quivering courtship dances for which peacock spiders are renowned, these sporty arachnids are living their lives with a level of athleticism our Olympic heroes can only dream of. Too bad they can’t go for gold in Brisbane.