| Common name | Greater stick-nest rat |

| Scientific name | Leporillus conditor |

| Type | Mammal |

| Diet | Herbivore, eating leaves and fruit |

| Average lifespan | 8 years in captivity and 5 years in the wild |

| Size | Between 17-26cm long, weighing between 180-450 grams |

The greater stick-nest rat is all about community. As its name suggests, this native rodent builds a large communal home out of sticks and stones, with cooperation and teamwork with other rats the key to its success.

Once driven to extinction on mainland Australia, the greater stick-nest rat has a small population on the Franklin Islands in South Australia and conservationists are working hard to re-introduce the species back to other parts of the mainland in the hope of saving this fluffy creature from extinction.

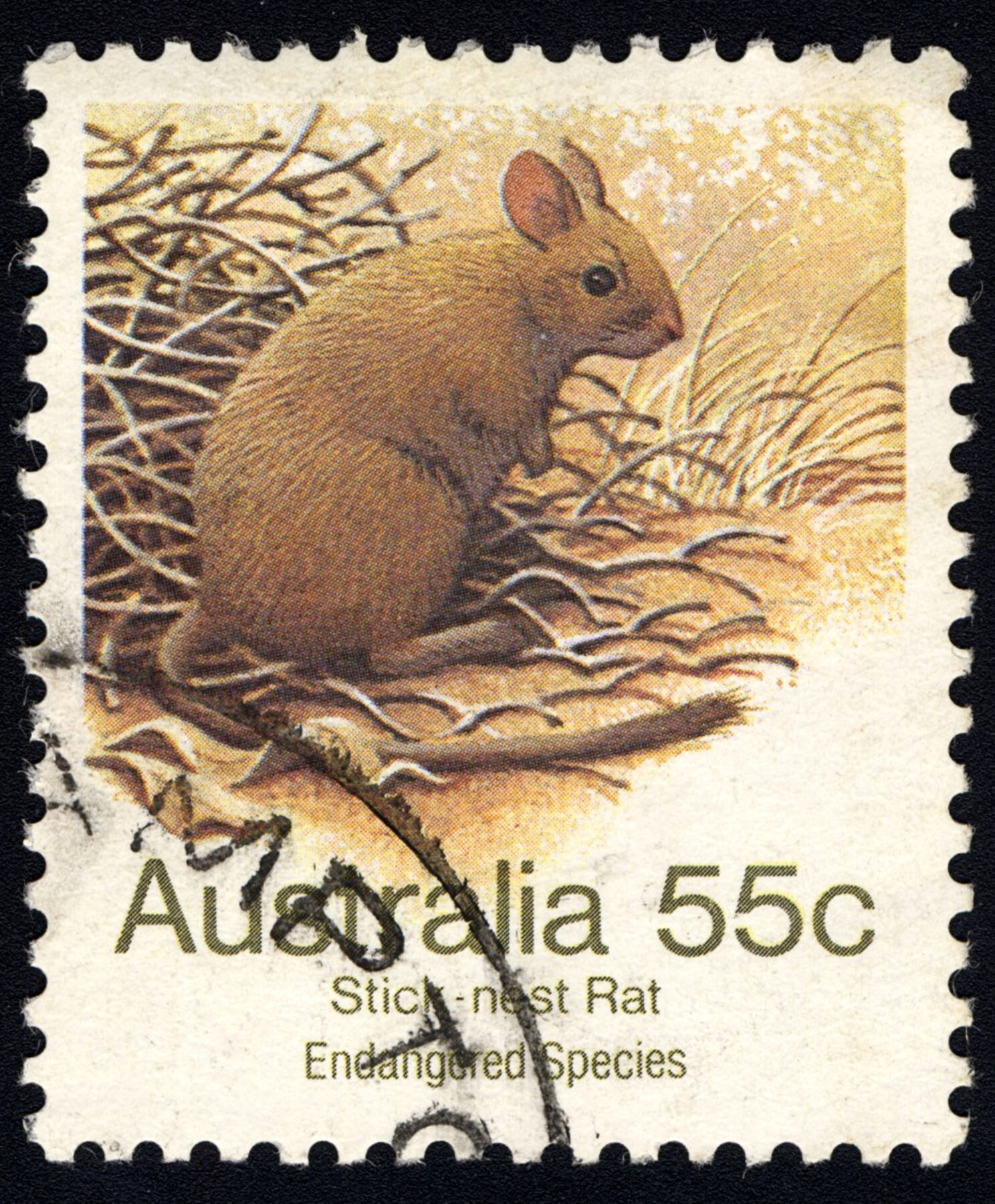

Also known as wopilkara, this native rodent is yellowy brown to grey with a creamy underbelly, a large head with large eyes, a blunt snout, and rounded ears. With a long, dark brown tail that is light brown on its underside, the greater stick-nest rat has special white markings on its upper feet and rests in a hunched position that’s similar to the stance of a rabbit.

Before European colonisation, the greater stick-nest rat could be found in arcs along the south-eastern, southern and south-western boundaries of Australia’s arid zone, from western Victoria to Northwest Cape. By the 1850s, the species was incredibly rare and could only be found in areas that hadn’t been turned into grazing land and by the 1930s, the greater stick-nest rat had become extinct on mainland Australia.

With its only natural population living on South Australia’s Franklin Islands, a captive breeding program began in 1985 using a selection of these animals in the hope of boosting animal numbers and one day reintroducing this guinea pig sized rodent back to the country’s mainland states as well as other Australian Islands. Current population numbers of stick-nest rats indicate reintroduction success at several specific sites, which spells good news for the future of the species.

A ground-dwelling animal, the greater stick-nest rat prefers semi-arid to arid perennial shrubland, especially consisting of succulent and semi succulent plant species. Rodents can survive with little to no access to fresh water and they feed on the leaves and fruits of succulent plants and grasses.

The greater stick-nest rat are master builders, constructing extraordinary nests out of sticks, branches, and stones which they build on top of soft grass. Teams of between 10 and 20 rats work together to collect, pile and weave materials to create an elaborate nest with a central living area and numerous tunnels extending to the outside. Running repairs are constantly made to the structure by the community of rats, with nests sometimes reaching as tall as 1 metre high and 1.5metres wide and lasting for generations. Rats may also find shelter in rock crevices, birds nesting burrows and dense shrubland.

Strong bonds are established between breeding pairs as the animals look to reproduce during autumn and winter when food and water is plentiful. Female stick-nest rats give birth to between one and three young after a gestation time of 44 days. Young rats attach themselves to the mother’s teat and are dragged around on the animal’s daily duties until they wean at around one month of age.