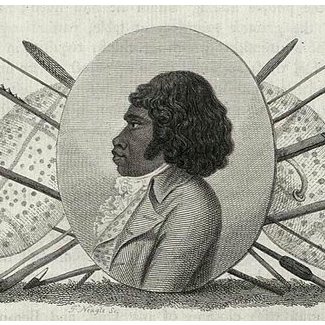

On this day: Bennelong was kidnapped

ON 25 NOVEMBER 1789, Woollarawarre Bennelong was captured by British settlers from the newly established colony of Sydney in the hopes that he would help the Europeans better understand Indigenous culture.

It was a moment that changed Bennelong’s life forever and history has told that from that moment, he was caught between two cultures, moving back and forth from the Aboriginal community and the British settlement throughout his life.

Bennelong’s capture and imprisonment

Bennelong came from the Wangal people and was captured on the order of then NSW governor Arthur Phillip. Phillip was under instruction from King George III of England to establish friendlier relations with the Indigenous population.

“You are to endeavour by every possible means to open an intercourse with the natives and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all Our Subjects to live in amity and kindness with them,” relayed King George in a letter dated 25 April 1787.

On 25 November 1789, Phillip’s men kidnapped Bennelong and kept him shackled in the settlement for the first few months of his captivity. In May 1790, once the restrictions on his liberty had eased somewhat, he escaped.

Life after the British colony

In September 1790 Bennelong was feasting on a whale in Manly Cove, along with a large group of Indigenous people, and invited Phillip to join him. One of the people then speared Phillip in the shoulder, perhaps as retribution for taking Bennelong.

Despite this, Bennelong maintained a friendly relationship with Phillip, learning English and even travelling to England with the governor and another Aboriginal man, Yemmerrawanie, between 1792 and 1795.

Dr Kate Fullagar, a historian from Macquarie University in Sydney, believes that Bennelong led a less tragic life than often assumed.

“Most historians, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, believe that he never settled back into his own culture after his trip to Britain,” says Kate.

“[Bennelong] left the [British] colony in the late 1790s because it became a horrible place.” Following this departure, says Kate, Bennelong seems to have resumed his place as a respected leader of the Wangal people.

Long legacy for Indigenous icon

The modern-day site of the Opera House, where Phillip had a hut built for Bennelong, is named Bennelong Point, in memory of the man who helped create the first cross-cultural communication between Indigenous Australians and British settlers.

Bennelong was also the first Indigenous Australian to have a federal electoral district named after him. This Sydney seat was, for a long period of time, held by former prime minister John Howard.

“Bennelong is important to remember because his initial friendship with the British brought other Aboriginal people into the cove and precipitated a short period of relative peace between both peoples,” Kate says. “He is also an example of someone who did survive the clash of cultures, and still commanded respect among his people in later life.”

RELATED ARTICLES