Ngaro dreaming

IT WAS ANOTHER cloudless day as I peer through the encrusted saltwater drops dotting my sunglasses. As I take another paddle stroke my blade connects with the ocean’s confused golden surface and droplets sparkle and dance in the sunlight. Between my position and the silhouette of a lush tropical Queensland coast, waves roll through the deep channels.

Behind a sporadic tree line consisting tall hoop pines, a glimpse of calm water reveals Nara Inlet, our destination for the day, and we just make out a brahminy kite circling over spectacular and mesmerising rock formations formed over thousands of years of wind and waves.

The calm waters are still a way off as our team of four kayaks makes headway in the lee of Hook Island, one of more than one hundred islands and islets that form the Cumberland Group – the largest group of offshore islands in Australia.

The ocean’s rhythm is hypnotic and I ponder whether the surrounding vista has changed much in the past 6000 years, when the rising waters at the end of the last ice age flooded the lowlands to create these islands. I contemplate whether the view was the same on 3 June, 1770 when a young Lieutenant James Cook sailed the Endeavour through this same passage on the festival day of Whit Sunday. Cook also noted the tall hoop pines (good for ship repair) and the plethora of sheltered anchorages, and he proceeded to name the location Whitsunday Passage.

While Cook continued north, our small team of kayakers instead slows pace, for this is the final day of our journey tracing the Ngaro Sea Trail. It is the first day, however in which we have encountered any sizeable waves, and smiles abound as we surf the small wind swells that roll beneath us.

The sun beats down, warming our torsos as we laugh and heckle each other’s attempts at running the swells. I notice a familiar sight out of the corner of my eye; a great green rock appears to rise from the ocean but the small, inquisitive head that rises from the glittering surface quickly reveals the true nature of the apparent floating boulder. A majestic green sea turtle turns my way for a moment, and it’s seemingly wise and knowledgeable eyes rest on me.

Maybe it is wary, knowing its ancestors were hunted by the seafaring Ngaro. Or maybe it is a juvenile, tripping from a natural high as a result of ingesting jellyfish toxin. (Yes, it is true!)

Apparently we are not interesting enough to retain the turtle’s attention, and it banks away like a big old Lancaster bomber, diving toward the depths of the ocean where it may remain for up to five hours without surfacing. We press on to Nara Inlet.

Canyons to Kayaks

It was less than a week prior that I had turned up bleary eyed, straight from a canyoneering project in Utah, USA, to the headquarters of Salty Dog Sea Kayaking at Shute Harbour. Here I met fellow kayakers Stu, Kim, Marney and our guide Alex Bortoli.

Scattered on the carpark bitumen lay multicoloured dry bags, PFDs, tents, food bags, satellite phones and UHF radios amongst a smattering of the everyday essentials needed for a multiday kayaking expedition. Quick introductions revealed that whilst Alex admitted to years kayaking the Queensland Coast, he originally hailed from Bermuda and grew up in the Bermuda Triangle. Of course, the ribbing about whether we would ever return began immediately.

I was still suffering jetlag when it dawned on me that going MIA might not be all that far-fetched; our first overnight camp was to be Dugong Beach in Cid Harbour on the western side of Whitsunday Island; a mere 20km as the crow flies, but most of it over open water running a reasonable wind swell.

“These guys are nuts,” I began thinking to myself. “I’ll die before we get a quarter of the way.”

Fortunately Salty Dog owner Neil rounded the corner at that precise moment and pointed to an approaching boat Scamper. “There’s your ride to camp one,” he grinned, as he saw the relief wash over my face.

With kayaks loaded and gear piled high in Scamper we departed Australia’s mainland in pursuit of our very own taste of the Ngaro Sea Trail.

A mere 10,000 years ago there would have been no need for aquatic craft and we simply could have walked to Whitsunday Island, however a melting icecap around 8000 years ago put an end to that. Like us (well, maybe not quite the same) the Ngaro people of the time had to adapt and it didn’t take long for them to become expert maritime hunters and paddlers.

High atop the ridge of South Molle Island en route to camp one is evidence of such adaptation; a scar in the landscape reveals one of the largest pre-European stone quarries in Australia. It was here the Ngaro people fashioned stone tools they traded as far north as Townsville and as far South as Mackay. Such widespread distribution of the Ngaro wares suggests they rapidly surpassed their mainland relations in terms of maritime expertise, and as expert navigators they paddled huge distances between islands.

Interestingly, whether the Ngaro used outrigger canoes or the more traditional three-piece sewn bark canoes has been and ongoing debate amongst academics and historians for many years. Research now suggests the Ngaro probably used both, with evidence from Cook’s log noting, “On a sandy beach upon one of the islands we saw two people and a canoe with an outrigger that appeared both larger and differently built to any we had seen upon the coast.”

Garden of Eden

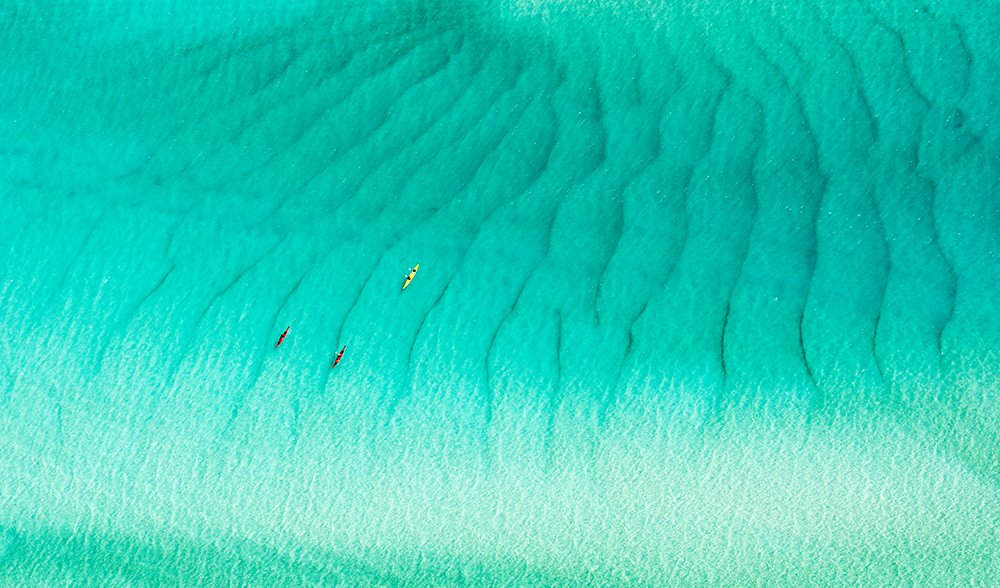

Arriving at Dugong Beach Campsite, we offload the kayaks and stores before rapidly setting up camp. From the campsite, only metres up the beach, small schools of baitfish are visible sheltering close to the shore, while beyond the shallows the fine silica particles in the water scatter and reflect light to offer a visual bombardment of brilliant and vivid tones of aquamarine.

With not a cloud in the sky, the water beckons us, and so rather than a short walk to Sawmill Beach, we load into the kayaks. Kim and Marney team up in the double kayak, whilst Alex, Stu and myself settle into the singles, and soon we are gliding across the calm waters of Cid Harbour, the occasional turtle head bobbing and breaking the surface, but alas, no dugongs.

As we paddle, Alex explains it was not only Captain Cook and the Aboriginal people who embraced the deep sheltered natural harbours of the Whitsundays. In fact, in 1942 the entire Pacific Fleet used Cid Harbour as a staging area prior to the Battle of the Coral Sea. From outriggers to tall ships to warships, the maritime history of the Whitsundays is astounding.

From the beach, a steep trail heads up to the 435m Whitsunday Peak, and peering along the dark trail leading onto the thick vine forest, thousands of blue tiger butterflies can be seen fluttering in the dappled light.

Following the rocky bed of a stream, we soon come across standing fresh water, evidence of the water source that drew the Ngaro to live here.

Such an environment was a veritable Garden of Eden for the Ngaro, who used the resin from the giant hoop pines to seal canoes and fix spearheads. They also made spears from hardened grass tree shafts, wove baskets from the leaves, made sweet nectar drinks from the flowers and ate the soft crowns as a vegetarian delicacy.

Following the trail through this Eden is a bit of a sweat-fest, but the view from the top makes it all worthwhile, as does cooling off amongst the coral reef surrounding Orchid Rock and the mesmerising paddle home on a sea of molten gold.

Pulling our kayaks ashore at camp we are welcomed by a white-bellied sea eagle high above, and enormous lace monitors wandering camp. Tuna and mackerel leap from the water as we eat our fill and peer into the darkness, where a Proserpine rock wallaby tentatively peers back at us.

Our first day in Paradise has been a good-un.

Sounds in the Night

As day two of our inter-island adventure dawns, the rustling of the night gives way to the singing of birds and whooshing of waves. Peering from my tent I notice a movement in the undergrowth; a small mouse hops out of a hollow log, scurrying around looking for food, and vanishes in an instant when it sees me. I step barefoot onto the sand wondering whether the early hours leaf-litter party that woke me had been this little guy and his mates, but then I notice a discrepancy; where Alex’s brilliant yellow tent once stood now stands an orange and red polka-dot dome.

As Alex emerges and looks at his roof, he groans in apparent understanding. He had inadvertently set up camp under a damson fruit tree, which is a favourite with the local fruit bats. While the Ngaro used to use the bark of this tree to poison fish, the previous night the fruit bats had gorged on it, in turn dripping the juices and berries all over Alex’s tent.

A hot cup of tea soon melts Alex’s ‘tap, tap, tap’ nightmares away and breakfast in paradise charges our team for our intended day of paddling Whitehaven Beach and Hill Inlet.

In our bid to cover as much water as possible we hitch another ride with Scamper and dump our gear at our overnight camp. Ideally this leg would be a nice paddle but unfortunately we all have commitments back home, and still have much to see, with an exploration of Whitehaven on the must-do list.

With its brilliant white beaches and cerulean waters, Whitehaven is a picture of nirvana, as enticing to the hardened adventurer as it is to the sarong-clad tourists who flock here from nearby island resorts – but it was not always such. Each squeaking footfall on the powder-like sand leaves a small imprint in the remnants of a once violent volcanic past.

A mere 100 million years ago (or thereabouts) when New Zealand chose to tear itself away from Australia, the split caused massive upheaval and volcanoes spewed out millions of cubic metres of silica rich magma. That same magma eroded over many millennium and was eventually washed by sea currents and sculpted by wind to become the largest silicic large igneous province in the world… or in layman’s terms, a brilliant beach of 99 per cent white silica sand.

I find myself a little shutter-happy and spend most of the day photographing (including hitching a ride in a helicopter) while the rest of the crew get stuck into 15 gruelling kilometres of paddling to the northern end of the beach and Tongue Point, before returning, close to broken.

I rejoin them midway back to camp and I can see the long day has taken its toll. As we silently contour the small breakers, the dark shadows of common stingrays glide beneath our kayaks, and the water surrounding us turns to glass as we quietly steer towards home.

Alex and I detour to a rumoured coral garden off Hazelwood Island 1.5km from camp, and the extra paddle has our muscles threatening to cramp, but a quick underwater exploration proves the rumours true, and the brilliant blue, green and purple soft and hard corals make the trip well worth the effort.

As we eventually glide back to camp we are once again inundated by wildlife. An inquisitive green sea turtle cruises into our cove where we bathe, and on reaching our camp we find the usual lace monitors hanging around and looking on casually

It is dinnertime when the real show begins with wallabies peering in from the tree line before ‘mission impossumble’ makes a dramatic entrance.

Sneaking up behind Alex and Marney towards our dinner, an acrobatic possum then makes a daring climb up Marney’s leg before launching onto our table and burgling some dinner. Marney ends up in Alex’s lap and the wry possum seems to wink at us before making a dash for the trees. We cannot help but laugh at the bold intruder as we double secure our food for the night.

Hamper Scamper

Three days in and we are becoming quite acquainted with good ole Scamper as we once again hitch a ride to the most remote island campsite of Whitsunday Cairn. Yet again, with time on your side, this would be a nice paddle with a halfway stop at Peta Bay, but once again we have our wishlist and time constraints to abide by.

We arrive at Whitsunday Cairn in time to tackle a slightly overgrown and ridiculously steep bush track for the 1.5km hike to the top. At the summit is a 360 degree view of the surrounding islands and we marvel at the spectacular vista laid out before us.

On soaking up the view, we rush down past scrub ebony trees, whose fruits turn from green to red when seeds covered with a brown pulpy sweet flesh ripen enough to eat. There are no ripe berries on hand but fortunately Hayley from Salty Dog has sent a bundle of treats aboard Scamper for our last afternoon out and we scoff on olives, dips and flatbread with cheese and salami before spending the afternoon exploring the coral gardens and enjoying a last night in this opulent wilderness.

Full Circle

We leave camp early in the morning to avoid the weather but it is slowly catching up with us. Our crossing of Hook Passage is uneventful bar the sighting of some feral goats wandering the shore at Fossil Beach, but the wind has continued to strengthen and for the first time in the trip we need to affix our spray decks.

After 10km of paddling, we near the end of our journey and while the sky remains clear, the wind continues to strengthen and we are relieved to enter the sheltered waters of Nara Inlet. It is here that the largest population of the Ngaro once lived due to its sheltered position and permanent freshwater source.

As we skim along the abstract rock formations lining the shore, we spy shell middens and ochre paintings on the caves and rocks overlooking the water.

According to University of Southern Queensland archaeologist Professor Bryce Barker (an expert on Ngaro culture), some of the caves show occupation stretching back almost 9000 years! This is “the oldest (aboriginal) site discovered in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and one of the oldest sites so far discovered on the East coast of Australia”.

Professor Barker says the Ngaro were not only expert navigators and maritime hunters but they also developed new technologies like the detachable, barbed harpoon point, which meant they could hunt larger animals like dugong, giant turtles (weighing 150kg-plus) and even small whales.

In Nara Inlet we finally come to the end-point of our trip and walk up to the cave paintings where a solar-powered speaker box eerily projects the voices of descendants of the Ngaro, telling the story of their people.

Through these days of following the sea trail I have learnt just how resilient and resourceful the Ngaro were in an ever-changing world, but I feel somewhat disheartened knowing that the history of the Ngaro is rather a sad story. For all their skills and seamanship, resourcefulness and knowledge, the Ngaro eventually fell victim to an ever-growing colonial settlement. Their peaceful and amicable relationship with passing boats failed when white pioneers began arriving with intent to stay. Fierce resistance led to the deaths of a dozen settlers and a number of ships were set alight, and the peaceful times were over.

By the early 1920s enough European disease and slave trading for the pearling industry resulted in the decimation of the Ngaro population.

This is a part of our history we must never forget and whilst I am saddened to learn of it, I am also thankful that I have experienced a small part of the Ngaro world and have had the opportunity to appreciate the majesty of their environment.

Over the past four days I am gladdened to have paddled alongside the turtles and jumping mackerel, to have slept alongside lace monitors and Proserpine rock wallabies, and to have ever so briefly touched on a world today that’s much as it would have been thousands of years ago.

READ MORE:

- Beginners’ guide to sea kayaking

- Destination: Whitsunday Islands

- Tropical oasis of Magnetic Island

- Explore the South Cumberland Islands, QLD

- Top 12 paddling spots in Australasia