Mike Hamill is at home in the mountains. He pretty much wrote the book on mountaineering. Literally! (I’m not kidding! Search Climbing the Seven Summits on Amazon). Across his mountaineering career, Mike has summited Everest six times, and guided more than twenty 8000m expeditions. He’s accomplished those famed ‘seven summits’ six times, cycled unsupported across the United States, ski toured to the South Pole, and the list goes on. In short, he’s no underachiever.

Personally, I should probably have a man-crush on this chiselled Yank mountain guide, but I have issues with Hamill, in fact I have a HUGE problem with the bloke… Because it’s mid-July in the Aussie Alps and he’s standing over me laughing. And what’s worse is I deserve it.

You see, when Mike first moved to Australia, I joyously discovered that for a guru of 8000m Himalayan peaks, he wasn’t so confident at 80m above sea level, on Sydney’s rutted, off-camber, sandstone mountain bike trails. His lack of confidence likely stemmed from having smashed his femur to bits riding a mountain bike only a few years previous, but that didn’t stop me dropping a few heckles. “C’mon mate, it ain’t Everest,” I jeered with a grin. In return he grinned back, and quietly suggested he’d get his own back one day. I thought to myself, “not likely mate. You won’t find me hangin’ in the death zone,” and so the heckling continued unabated.

Payback time

Now, on the semi frozen banks of the Snowy River in Kosciuszko National Park, Mike is getting his own back. He’s at home amongst the snow and ice, even if it is my own Aussie backyard rather than his usual playground of high-altitude Antarctica or the Himalayas.

We’re at the suspension bridge at Illawong, in the backcountry. The bridge hangs over the swift moving waters of the Snowy River and is a gateway to Australia’s ancient and weathered alpine peaks. This portal to adventure lies a rather short slog (that incorporates a painful snow gum-strewn sidehill traverse), from the trailhead, two and a half kilometres back at Guthega. It is also a transition point for Mike’s Australian Alpine Training Academy where our team of future mountaineers launches into the nuances of hauling a heavy sled of gear across frozen white stuff. The banks of the Snowy also happens to be where my 10-year-old snowshoes explode into a million tiny pieces…

It occurred to me, too late, that a decade of UV and freeze/thaw cycles on plastic bindings might to lead to what some term ‘a critical failure of structural integrity’. Me… I call it, “up a creek without a paddle.” Maybe I should have ticked the checkbox beside ‘hire equipment required’. My “she’ll be right” attitude was now biting me firmly in my frozen backside. And to top it off, underneath Mike’s look of concern, I know he’s quietly laughing at me. In fact, he’s not even being quiet about it, and as promised he is getting his own back by suggesting I should be savvy enough to find a solution and catch up to the team later that day. I’m less confident in my own abilities.

Fatefully, I do have a backup. A set of lightweight ski-touring boots and a split-board (snowboard that splits into touring skis) sit in my car back at Guthega. It’s worth a try. I inform Mike I’ll hightail it back for my gear and send a message if I think I’ll be able to re-join the team.

With plan in place the alpine academy crew traipses into the vastness of the Kosciuszko main range while I stash my pack under a rock and begin a jog (as much as you can jog in mountaineering boots on a thawing crust) back to Guthega.

Footprints to nowhere

A few startled snowshoers out for a backcountry stroll look quizzically at me as I shuffle past in high-tech mountain gear. I imagine them pondering, “who is this hardcore athlete training for a speed ascent?” Little do they know the truth.

Keeping to shadows to avoid a rapidly thawing snowpack, I manage to sweat it back to the suspension bridge with replacement gear in just over two hours. Donning a now overladen pack bulging with extra boots, PLB, shovel and a bivvy bag, I start off into the vastness of the main range following a snowshoe track south and practising the smug look I will offer Mike on my catching the team aboard my split board and new go-fast climbing-skins*.

Thirty minutes into my solo journey and my smugness wanes as cracks begin to appear in my plan. My first, rather disconcerting realisation, is the snowshoe trail I’m following splits into two. Suddenly I’m in a ‘choose your own adventure’ novel with the results of a wrong decision steering me to a cold solo night in a bivouac, and most likely ending in a backtrack to Guthega with head hung in shame. I look south where footprints traverse the Snowy, then west, where a second track climbs toward the summit of Mt Twynham, Australia’s third tallest peak.

Fortunately, I guess right (it was left) and head southward on more well-trodden tracks to eventually find my team’s sled stash point. This leads to the second crack in my plan…I have no sled.

I’ve stripped to my base layers pushing hard to the stash point, but unaware whether I’d follow the same path, the crew took all the sleds – and they are now a long way off, somewhere in the vast white between myself and Mount Kosciuszko. All I can do is suck it up, and skin my way south with nothing but myself and my thoughts for company.

Late in the afternoon an old groin injury begins to cramp, I suddenly feel old, and my team is still nowhere in sight. I don a headtorch as the light begins to fade and tracks become harder to discern. The brilliant blue sky turns gold and then to pink. As the first stars begin to appear, underlying concerns grow exponentially into full blown anxiousness. I am yet to find my team and it’s starting to get late. Fortunately, I’ve got food, a sleeping bag and bivvy, so I can always bail out to Charlotte Pass, but I’m not sure I’d ever live it down. A flash of a headtorch in the distance is my saving grace.

By the time I limp into camp, my well-rehearsed smug look is long gone and has been replaced with a look of relief and exhaustion. Mike grins at me and congratulates me on not dying. It’s day one and he’s already got his own back.

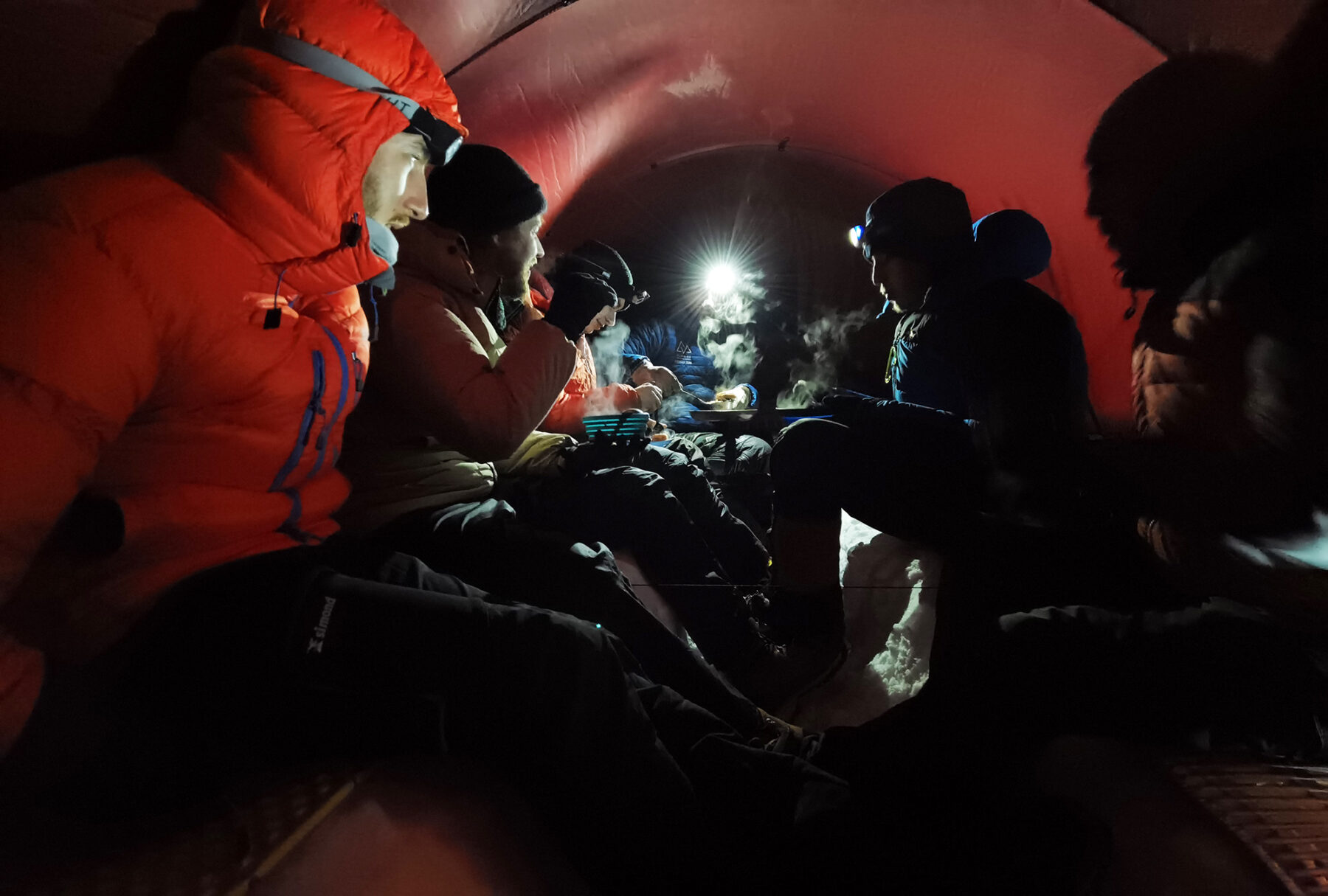

Rather excitingly the crew have already dug out tent platforms and erected nearly all the tents. Not long later I am eating hot salami and toasty fajitas washed down with a splash of spiced rum in a warm mess tent. As I thaw, I begin to realise my training in “how not to die in the mountains” has already begun with lesson one: triple-check the integrity of your gear, and lesson two: always carry enough survival gear for an unexpected night out. Tomorrow, we launch into crampon technique, roped glacier travel, self-arrest, and knots. It’s going to be a full-on few days.

Learning the mountaineering ropes

What I quickly learn of Mike Hamill is, he likes food. There’s no freeze-dried on this trip and the sleds from yesterday’s long haul to base camp were most likely included less for training and more for the haulage of cheese, salami, pasta, pancakes, maple syrup, kalamata olives, smoked salmon, and anything else you might need for gourmet meals in the mountains.

Emerging from my tent to a still pink sky on morning one, I note steam rising from the door of the mess tent. I beeline to the radiating warmth of a dual burner gas stove in time for Hamill to explain.

“Just because we’re in the mountains doesn’t mean that we must suffer. Happy and well-fed climbers are successful climbers, and that goes both for Australia and the summit of Everest. We eat well across all our programs, and while it might mean a heavier load to carry in, I guarantee it pays dividends.”

He doesn’t disappoint, with hot porridge, thick pancakes, and copious amounts of freshly brewed coffee for breakfast. By the time the sun is melting the hoar frost on our tents we are warm, fed, and ready for a full day of hands-on learning.

Now I’ll gently blow my own trumpet and let you in on a secret. I have in fact played on a few frozen expeditions previously, in Oz, NZ, Alaska and even the Canadian Arctic.

What I discovered on all previous expeditions can be summed up in two key rules:

1. Respect the mountains (we are insignificant when compared to the power of mother nature)

2. There’s always more to learn (I haven’t scratched the surface, even with a few projects under my belt)

And thus, our mixed bunch, with varying experience on-snow, listen intently as we launch into basic crampon technique followed by self-arrest for when shit goes wrong.

“Self-arrest is one of the most important skills you will learn.” Mike explains.

“If you fall on a steep face then whether you are textbook or not, your sole goal is to arrest your fall. Use your ice axe, a rope, an anchor, a rock, your pole, or crampons, or if all else fails, use your fingernails. Whatever it takes. Failure to stop is not an option.”

We spend hours sliding down a slope. Upside down, right way up, feet first, headfirst, bum first it doesn’t matter. In the end we all soon get it; axe in, rotate body appropriately, slow descent, kick boots in, STOP! I will admit, there are plenty of laughs had, but all with a hint of reservedness: we all know in a real-life scenario a misplaced step can be disastrous.

As the sun climbs high, we cover off climbing efficiency, glacier travel and rope techniques and finally, as the shade from Carruthers Peak creeps over us, we head back to the warmth of a mess tent where hot smoked salmon and pasta fuels the body whilst we continue to cover off rope-work and knots into the night.

Summit, sastrugi and self-rescue

Day two dawns to another crisp morning and we’re up early to fuel up. The key objective for the day is to traverse Mt Clarke, cut under Mueller’s Pass and summit Australia’s highest peak Mt Kosciuszko, all in time for an easy return to basecamp before the predicted weather rolls in.

My exploding snowshoe disaster now bodes well for me. My split board and climbing skins make for far easier travel compared to mountain boots and snowshoes. I am revelling in the ‘kick and slide’ of my split board as the day wears on and I am rewarded further with the discovery of wind-blown powder on the eastern flanks of Kosciuszko. My froth meter begins to soar with the realisation I will score an epic descent when returning to camp later.

Selfishly, I imagine long arcing high-speed turns enroute to camp before settling into a sleeping bag for hot chocolate whilst the others slog it out on snowshoes. My reverie however is interrupted when we run out of ‘uphill’ and the summit cairn of 2228m Kosciuszko stands before us.

To the north lie the weathered peaks of the Main Range’s highest points of Twynham, Townsend, and Carruthers, To the east, the high plains of the main range and headwaters of the Snowy River. Southward lies the majestic Cootapatamba Cirque and the Rams Head Range and to the west, the layered peaks of the Victorian Alps. Kozi might not be the mightiest of the seven summits, but it certainly does not lack appeal.

As we refuel, sheltering behind summit rocks, the light begins to flatten and soon the Victorian Alps are nowhere in sight. I realise too late that Mother Nature has stepped in to check my ego and remind me nobody is rewarded for busted gear stupidity; the cloud rolls in and snow begins to fall. We begin the long slog home.

My intended sweet turns become a ridgeline sastrugi-riddled obstacle course followed by a slow, careful descent to the southern flanks of Mt Clarke. Rather than hot chocolate and a sleeping bag my journey to basecamp becomes a trudge. At one stage, I change over to snowboard again and scoot down Clarke Cirque only to break through a snow bridge into the trickle of a semi-frozen stream. I’d like to say I used my new-found crevasse rescue skills to escape, but a spread-eagle-worm-like wriggle succeeded before any textbook self-rescue techniques were required. It was a reminder however, not to get blasé about backcountry travel.

By the time we get back to camp, large snowflakes fall gently. We settle into our last night with another feast of hot food, and the sound of snow sliding from tent fly sheets.

Mountaineering equals character building

Now I won’t pretend our final-day slog back to Guthega was fun. It was, instead, ‘character building.’

The falling snow eventually became rain and soon enough, we were sloshing through a fast-disappearing snowpack. By the time we traversed the maze of snow gums between Illawong and Guthega, the snowpack had diminished just enough for the sleds to tangle on the now protruding undergrowth. I won’t lie, the going was tough.

By mid-afternoon we were finally out. We were sodden, exhausted, and the long, wet slog home had tested team spirit. But we’d continued to work together. Loads had been redistributed, upturned sleds righted by those slogging behind, and even gear shared to better help somebody else. As haggard a lot as we might have appeared, we were all grinning under our hoods.

Our Climbing the Seven Summits Winter Alpine Academy was certainly no walk in the park. The entire team had been tested at times, but star-filled nights and windless bluebird days were our reward. We had absorbed about as much backcountry knowledge as is possible and threw in a winter ascent of Kozi to boot. I realised underneath Mike’s cunning grin lies a natural born guide; his ability to teach and problem-solve on the move, in between catering to the needs of a mixed group, is an art.

Yep, there were hard times, frozen digits, blisters, and a long slog out. But life in the backcountry, learning mountaineering skills, is not meant to be easy, it is supposed to rewarding.

The mountains don’t care who you are, what your gender is or whether you have an ego. They welcome you if you respect them and they school you if you don’t. Most importantly, they laugh at you if your snowshoes explode.

If I only take away one lesson from this experience it will be to triple-check my kit. Oh, and never heckle a Yank mountaineering legend, for he will always get his own back – and most likely, on day one.

See Climbing the Seven Summits for more info on alpine climbing courses.