Northern lights dinosaur was savage predator

John Pickrell

John Pickrell

DR PHIL BELL, who works with Australian Geographic on our annual Lightning Ridge fossil dig, has discovered a new species of predatory dinosaur related to Velociraptor.

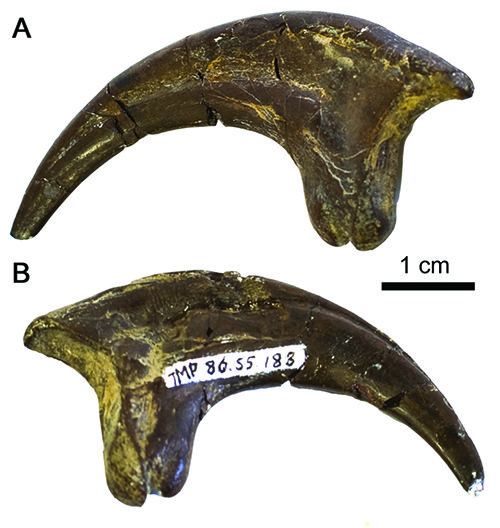

Despite being no bigger than a large dog, the newly discovered animal would have been a swift runner and a nasty piece of work, says Bell. “It had rows of small, serrated teeth, like mini steak knives; three large talons on each hand; and a foot equipped with a trademark sickle-like claw, that it could use like a grappling hook to latch onto prey.”

Bell – who is based at the University of New England in Armidale, NSW – spends part of each year working on fossil digs overseas in places such as Mongolia and Canada, and this latest discovery was made in Alberta in 2012. The find is detailed in a Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology paper he co-authored with seasoned Canadian dinosaur hunter Phil Currie.

Dinosaurs under the northern lights

Boreonykus certekorum, as they have called it, lived in the Grande Prairie region of Alberta 73 million years ago, during the Late Cretaceous. The name Boreonykus comes from the Greek ‘borealis’, meaning northern, and ‘nykos’, meaning claw.

The fossils were found in the boreal forests that encircle the world at high-northern latitudes from Canada to Europe and Siberia. “You can also see the spectacular aurora borealis northern lights at those latitudes,” Bell says. “The sickle claw from the foot was also one of the first bones found, so all those elements came together to lend the species its name.”

The initial discovery of fossil bones was made in 1986, but experts assumed they belonged to an animal already known, and so they lay unstudied in the collection of the Royal Tyrrell Museum for a quarter of a century before he found them in 2010. Bell was then part of the expedition that discovered more Boreonykus bones in 2012.

The sickle claw from the foot of Boreonykus (Credit: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)

The enigma of Boreonykus

“I became fascinated with this animal, as small carnivorous dinosaurs from these latitudes are extremely rare,” he says. “After a bit of poking around, we realised that these were not the bones of Saurornitholestes, Dromaeosaurus or some other known species, but something new and unique to this region.”

Seventy-three million years ago this part of northern Canada was even further north than today. Though global temperatures were then high, there would have been long periods of complete winter darkness, when plants wouldn’t have been able to get energy from the Sun and ecosystems virtually shut down.

“Herbivorous dinosaurs would have migrated or hibernated, leaving hungry carnivorous theropods in their wake,” Bell says. Experts have long wondered what carnivores at high latitudes ate in winter, especially as fossil finds in recent decades have shown a wide diversity of predatory species.

“Boreonykus is one more enigma. We don’t really know what they did during the winter months. Small land animals such as this don’t migrate well. It’s too exhausting. Similarly, modern carnivores tend to stay in their home areas over winter even when the bigger, herbivorous game leaves.”

Feasting on rotting ceratopsian dinosaurs

Some of the Boreonykus fossils were found broken and scattered among the bones of Pachyrhinosaurus, four-tonne herbivorous dinosaurs related to Triceratops. Shed Boreonykus teeth were also found at the same site. The scientists speculate that these small predators were probably dining on the rotting, bloated carcasses of the pachyrhinosaurs during winter.

Bell says that the discoveries in Canada go hand in hand with the fossil work in Lightning Ridge in Australia, which was also at high latitude, near the Antarctic Circle, during the Late Cretaceous.

“Having an understanding of how these two relatively high-latitude ecosystems (one in the north, one in the south) work, is really complementary,” he says. “The animals may be wildly different, but the questions are the same: ‘what species do we find?’, ‘what are the similarities?’, ‘how did they survive in these challenging environments?’.”

John Pickrell is the author of Flying Dinosaurs: How fearsome reptiles became birds, published by NewSouth Books. Follow him on Twitter @john_pickrell.

Dr Phil Bell (at left) and Dr Federico Fanti sort opal mine tailings on the 2015 Australian Geographic Lightning Ridge Scientific Expedition (Image: John Pickrell)

Dr Phil Bell (at left) and Dr Federico Fanti sort opal mine tailings on the 2015 Australian Geographic Lightning Ridge Scientific Expedition (Image: John Pickrell)

Want to join us on an Australian Geographic fossil dig? Learn more about our expeditons to Lighting Ridge and Mongolia’s Gobi Desert.