The incredible shrinking dinosaur

John Pickrell

John Pickrell

I KEEP PLANNING to write about something other dinosaurs on this blog, but it seems that week after week an exciting new discovery is announced. This time it’s the turn of an international team led by South Australian Museum scientist Associate Professor Michael Lee.

Birds are descended from dinosaurs, in fact they are a small, specialised, flying form of theropod dinosaur – of this there is no longer any doubt. What has been puzzling for experts is how creatures as massive as one of the larger dinosaurs could have evolved into something as dainty and diminutive as a songbird.

What may be the largest dinosaur, Argentinosaurus, weighed around 100 tonnes and was more than 30m long. The smallest member of the dinosaur family is the bee hummingbird, found on Cuba today. Its body is scarcely bigger than an insect’s, measuring just 5cm from beak tip to tail tip, and it weighs less than 2g. A single Argentinosaurus weighed as much as 50 million bee hummingbirds.

Amazing flexibility of the dinosaur body plan

This staggering figure illustrates the amazing flexibility of the dinosaur body plan, which has adopted more shapes, styles and sizes than just about any other group of animals, but it also suggests that miniaturisation was an essential prerequisite for flight. All animals that have achieved flight started out small, and dinosaurs were no exception.

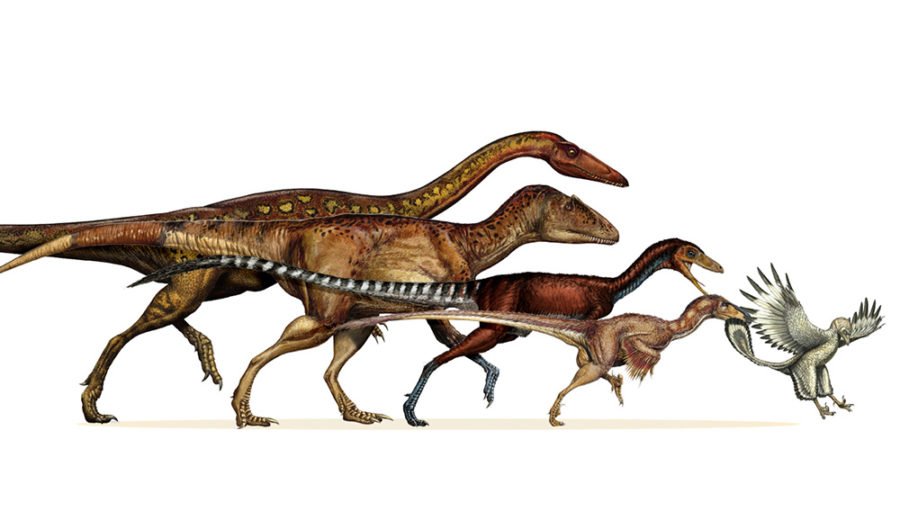

What Michael Lee and his team have now shown is that a sustained process of miniaturisation over 50 million years in the lineage that led to birds caused a 12-fold reduction in size. Large carnivorous dinosaurs, akin to Ceratosaurus and Megalosaurus, shrank in size from an average 163kg to just 800g by the time of the ‘first bird’, Archaeopteryx, 150 million years ago.

The rate of evolutionary change in this lineage was 150 times normal background rates, say the researchers today in the journal Science.

To make the discovery they looked 1549 small features of the skeletons of carnivorous dinosaurs and early birds, and used them to create a new family tree. They then mapped rates of evolution over time on this tree.

“Birds evolved through a unique phase of sustained miniaturisation in dinosaurs,” Michael told reporters. “Being smaller and lighter in the land of giants, with rapidly evolving anatomical adaptations, provided these bird ancestors with new ecological opportunities, such as the ability to climb trees, glide and fly.

This video below, from authors Michel Lee, Darren Naish, Andreau Cau and Gareth Dyke, illustrates how birds arose from a very special lineage of evolving dinosaurs.

How birds survived extinction that killed the dinosaurs

Intriguingly it may be this adaptability and rapid rate of evolutionary change that allowed birds to survive the mass extinction event that killed off all of the other dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

“It turns out that the longest lived lineage of dinosaurs was the most evolvable and adaptable,” Michael added when I spoke to him this week. “This flexibility helped birds survive the meteorite impact.”

And birds had already developed a suite of features that pre-ordained them to make it through the cataclysm at this time: they could regulate their body temperature and stay warm in the post-impact winter (something like a nuclear winter in its effects), they could also fly to escape from wildfires and search for food; finally their small size meant they could survive on much less food than a 100t sauropod. No animal heavier than 25kg in size is thought to have made it through the extinction event alive.

But what was the driver of miniaturisation? It can’t have been flight, as that came later, and evolution is a random process that doesn’t have that kind of foresight.

Writing in the same issue of Science, palaeontologist Michael Benton thinks he has the answer. It may not be to do with flight, but another key trait of many birds: living in the trees.

Birds are dinosaurs that moved to the trees

“The crucial driver may have been a move to the trees, perhaps to escape from predation or to exploit new food resources,” writes Michael, who is based at the University of Bristol in the UK.

“Tree living requires small bodies, and reduced body size enables other characteristics that enhance success in the trees, such as enlarged eyes for three-dimensional vision (so avoiding collisions when leaping from branch to branch); enlarged brains to cope with diverse arboreal habitats; insulating feathers to enable nocturnal activity (many insects are nocturnal to evade cold-blooded predators); and elongated forelimbs…with expanded flight surfaces to enable ever more daring leaps from tree to tree.”

Indeed he says these it may have been tree living that led to enlarged eyes, enlarged brains and elongated arms in the primate ancestors of our own species.

See the Sep/Oct print edition of Australia Geographic to learn more about an expedition that will attempt to find feathered dinosaurs in Australia in 2017. There’s also a fantastic poster of Australian dinosaurs, which is free for subscribers.

John Pickrell is the author of Flying Dinosaurs: How fearsome reptiles became birds, published by NewSouth Books in June 2014. Follow him on Twitter @john_pickrell.