In 2023, ‘sustainable’ is more than just a buzzword. With the post-Covid resumption of travel, many travellers are choosing a different, gentler path. They’re giving extra consideration to how their travels affect the environment, other cultures, and the socioeconomic bottom-line of their destinations.

Not just another passing fad, sustainable and conscious travel is now mainstream.

But what does it actually mean?

What is sustainable travel?

Internationally, the lead organisation for conscious travel is the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), a not-for-profit organisation that sets criteria that act as global standards for sustainability in tourism.

While the concept of sustainable tourism may immediately bring to mind environmental aspects, according to the GSTC, the term encompasses four pillars. These are sustainable management, socioeconomic impacts, cultural impacts and environmental impacts.

Sustainable travel overlaps with many other terms. Conscious travel means actively thinking about where, when and the way we travel, and eschewing mass tourism. Cultural travel refers to travelling to learn about, and benefit those from another background. Slow travel is seeking immersive experiences rather than quick box-ticking, and regenerative travel means leaving a place better than you found it. All of these approaches to travel have the goal of travelling ‘for good,’ and increasingly, data show this is how people want to travel.

What travellers want

In 2022, Tourism Australia conducted a research project across prospective travellers in 20 key international markets. The results showed that over 75 percent of respondents were committed to sustainability in some way.

A broad range of sustainable practises were important to the respondents when travelling, including ethical treatment of wildlife, respecting and preserving the cultural heritage of a destination, supporting local businesses, off-setting carbon emissions and protecting natural environments.

Significantly, when presented with a range of experiences, around 80 per cent of respondents chose the more sustainable option.

Phillipa Harrison, managing director of Tourism Australia explains that while Australia has always attracted visitors for its fauna and environment, sustainability is now a factor in decision-making.

“Sustainable practises by tourism operators are no longer a nice-to-do, they are good business hygiene, and sustainability is no longer pigeon-holed as just environmental. It encompasses understanding of impact on culture and community too.”

These sustainable tourism operations do impact positively on the communities in which they operate. For example, Luxury Lodges of Australia, a portfolio of high-and lodges and camps operating in regions across Australia has measured their reach.

Penny Rafferty, executive chair of Luxury Lodges of Australia, explains the lodges deliver over 250 experiences.

“In order to do that, they partner with over 4000 other local businesses, from wildlife and specialist guides, Traditional Owners, transport and experience operators, artists, distillers, winemakers, food producers and craftspeople,” she says. “That is an enormous halo effect.”

The rise of cultural travel

According to Phillipa Harrison, another encouraging result of Tourism Australia’s recent survey was the increased attention given to Indigenous tourism.

“In terms of Australia’s tourism offering there is a very strong connection between sustainability and cultural travel, with our First Nations people arguably the pioneers of sustainability, with more than 60,000 years as custodians of country,” she says.

Phillipa explains there is increased awareness that Indigenous experiences can be found all over Australia, encompassing traditional and also contemporary experiences.

“Whether it’s exploring the coastline at Port Stephens on a quad bike with Sand Dune Adventures, to doing the Burrawa Bridge Climb experience, scaling the heights of the Sydney Harbour Bridge with an Indigenous guide, there is so much to do and experience.”

Further encouraging the growth of cultural tourism, various Indigenous tourism bodies are promoting businesses around the country.

Rob Taylor is the chief executive officer of the West Australian Indigenous Tourism Operators’ Council (WAITOC), and says in 2016, there were 65 Aboriginal tourism businesses in WA, mostly in the Kimberley. In 2023, the state is home to over 180 Aboriginal tourism businesses, an Aboriginal tourism academy and a dedicated business hub.

“You think about remote communities where there’s not much chance to make money,” Rob says. “Tourism allows them to keep culture alive by sharing language, sharing their knowledge while staying on country and earning money to live by, so I think it is an important industry.”

According to Rob, Covid-19 accelerated growth for Indigenous tourism in WA.

“The majority of Australians have never been on an Aboriginal tour, and wouldn’t have a clue what’s in their backyard,” Rob says. “But when the borders were closed, some of the areas like up in the Kimberley were even busier than when the borders were open because Western Australians couldn’t go anywhere else. So people were going to those areas and basically doing Aboriginal tours because it’s one of the things they probably haven’t done before.”

Beyond merely a fun holiday experience, Indigenous tourism can play a vital role in wider cultural understanding and reconciliation.

“Most Australians don’t know the real Aboriginal culture,” Rob says. “They only know what they see in the news, which is usually bad things. Just as many bad things happen with non-Indigenous people, but it seems to be highlighting all the bad things rather than all the good things. I think if they’re going along and learning about Aboriginal culture, they’ll better understand.”

Greenwashing versus sustainable

With sustainable travel now front of mind for so many travellers, it has become a lucrative sector. Many would like to cash in on the trend, and this can sometimes lead to false or embellished sustainability claims.

The term ‘greenwashing’ describes these dubious claims, and for many travellers, deciphering the greenwashing from genuinely ethical travel experiences can be a minefield.

One method of choosing a sustainable operator is to ask questions. Look for tourism operators who have committed to measurable achievements, rather than overarching statements, and are willing to engage in conversations on the topic.

Another way to travel more consciously is to seek tourism providers with a meaningful sustainability accreditation.

Internationally, many accreditations exist, of varying quality. In Australia, two companies offer programmes recognised by the GSTC, namely EarthCheck and the not-for-profit Ecotourism Australia. Both companies administer rigorous certification standards around conscious travel, and choosing a tourism provider displaying one of these certifications helps to guarantee the activity is sustainable.

Ecotourism Australia has been working in the conscious travel sector for more than 30 years. Initially, the focus was the Eco Certification programme, which certifies nature-based tours, accommodations and attractions.

Elissa Keenan, chief executive officer of Ecotourism Australia, explains that with the rise of conscious travel, the concept itself has evolved to more fully encompass GSTC’s four pillars of sustainability; social, environmental, cultural and economic factors.

“It’s not just about environment, although it’s incredibly important in terms of minimising impact,” Elissa says. “For example, people now have a far higher expectation that their travel positively impacts the local community.”

In recent years, Ecotourism Australia has expanded to recognise sustainability efforts across non-nature-based tourism businesses. Companies like breweries, city hotels and non-nature tours can now apply for the Sustainable Tourism accreditation.

Acknowledging that many business owners may not know where to begin their accreditation journey, Ecotourism Australia, in partnership with Tourism Australia has launched a new programme called Strive 4 Sustainability.

“Tourism operators are hearing this buzzword sustainability, but they’re not quite sure what to do with it,” Elissa says. “We’re hoping that this programme starts to demystify what that means. It’s really designed to answer the question for operators which we hear all the time – where do I start?”

The programme provides operators with a scorecard across the four pillars of sustainability, and advice on how to improve.

For some travellers, finding a sustainable tourism operator is not enough, and they prefer to visit a region where sustainability is embedded in the community. Ecotourism Australia now certifies Eco Destinations, and in 2019 the Port Douglas Daintree area, QLD, became the first destination accredited. The other certified Eco Destinations are Margaret River WA, Coffs Coast NSW, Central Coast NSW and Bundaberg, QLD, with many more applications in the pipeline.

Achieving Eco Destination status is a rigorous process, usually taking several years.

“Generally, the application is led by the local council,” Elissa explains. “The reason for that is because it includes so much about their infrastructure in terms of waste, water, and energy. But it also requires an absolute commitment from the regional tourism authority and from local businesses, really working together.”

According to Elissa, the benefit for the consumer is clear.

“What it says for a traveller is this is a destination that’s really committed to their sustainability journey,” she says. “They’re not necessarily just about visitor numbers and how to maximise them.”

Similarly, EarthCheck offers various science-backed certifications for nature-based and non-nature-based tourism operators and destinations. EarthCheck also has a sustainability academy, with micro-courses to help people and businesses embed sustainability into their organisations, including a design certification to assist developers to construct sustainable buildings.

The flying issue

Globally, aviation accounts for around 2.5 percent of all CO2 emissions. With Australia’s vast and isolated geography, aviation is the elephant in the room. While many airlines offer passengers the chance to offset their carbon emissions by contributing towards tree planting, it can be sometimes difficult to ascertain their effectiveness.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) represents airlines globally and has facilitated an industry movement to reduce aviation emissions to net zero by 2050.

Daniel Bloch, assistant manager of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) for IATA says biofuel-based SAFs will be the major contributor to reducing sector emissions until at least 2035. The SAF biofuels are made from feedstock, the first generation of which were typically food-grade crops and oils, which could potentially distort the agricultural economy.

Second generation feedstocks use various forms of waste fats, such as inedible animals fats, used cooking oil and trap grease, which would otherwise need disposal.

However even these waste fats are in limited supply, and third generation feedstocks are emerging; naturally or regularly occurring wastes from agriculture, woody residues, municipal solid waste and landfill. It can contain animal, food or human waste and even plastic.

“That really is an important distinction with biofuels,” Daniel says, “The feedstock is the determining factor in just how sustainable the biofuel will be. In essence, we want to be repurposing inputs that would have otherwise not have been utilised and sent to landfill or incineration, which in turn corresponds with a carbon emitting output.”

Along with a developing market for small electric aircraft, planes may soon be powered by green hydrogen, with Airbus already releasing prototypes. But for now, Qantas and Airbus, are planning to establish an Australian SAF industry and the Australian government has announced funding for a SAF Council, aimingto drive a domestic SAF industry.

Ways to travel consciously

Aside from aviation, there are already ways conscious travellers can choose more sustainable options. Many travellers seek to minimise their carbon footprint by reducing fossil fuel usage, and a people-powered mode of transport is an excellent choice.

Travellers may take a self-guided cycling tour of the Clare Valley wineries in South Australia, explore Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef by kayak, or discover Tasmania’s best multi-day hikes. There are many bonuses to these forms of travel, including the meditative connection to nature that comes from a quiet, slow journey compared with rushing through multiple destinations.

In pre-pandemic days, cruising was an estimated five billion-dollar industry for Australia, and Australians are the biggest cruising nation per capita. While the cruise industry itself is not famous for its sustainable practices, expedition cruising in particular (the more adventurous cruises to wild places) is finding new ways to be greener.

Several companies have incorporated hybrid diesel-battery technology, which is said to reduce carbon emissions by 20 percent. Engine heat is recycled to the cabins and water heaters. Kitchen waste and sewage are fed to the ship’s bio-digesters where enzymes reduce waste to a benign sludge.

Growing environmental awareness sees education and scientific research taking centre stage. Passengers join science lectures and participate in citizen science projects, such as seabird surveys and water quality checks.

Citizen science is on the rise in other tourism contexts, too, and the Great Barrier Reef offers prime examples. The programme called Eye on the Reef offered by many tour operators, asks visitors to upload photos from their snorkelling or dive experience to an App, which records where certain rare species, or pest species like the crown-of-thorns starfish, have been sighted. The information gathered helps to inform reef management.

The Great Barrier Reef is also home to regenerative tourism opportunities. Guests can be a ‘marine biologist for a day’ joining reef surveys, and divers can get hands-on with coral restoration projects, attaching pieces of naturally broken corals to a frame to help restore areas damaged by climate change or natural processes.

Other purposeful travel on the Great Barrier Reef includes visiting the Turtle Rehabilitation Centres at Fitzroy Island or at the Cairns Aquarium, where injured or sick turtles are cared for and hopefully released. Entry fees fund the necessary resources to rehabilitate the threatened turtles.

Regenerative travel is happening on the land too, including the restoration of wildlife habitat. In Victoria, visitors can join the not-for-profit Koala Clancy Foundation to plant koala habitat trees.

For those who don’t want to get their hands dirty, there are ways to support others regenerating the land.

Many food and wine producers are opting to heal their degraded properties by farming in ways that are gentler on the land, using integrated pest management (like employing ducks to eat the snails), permaculture (where all organic waste is recycled into usable nutrients) and reducing chemical usage. Travellers can connect with these producers at farm-to-table restaurants or by visiting organic cellar doors.

Even some huge cattle and sheep stations are trying to heal the damage of decades of overgrazing. In Western Australia, the owners of Wooleen Station are supplementing their income with tourism while they vastly reduce stock and grazing pressure on their land, offering hosted stays in their historic homestead and regenerative agriculture tours.

Indigenous tourism is often intrinsically linked to regenerative activities. Near Cairns, the Mandingalbay Hands On Country Eco Tour combines a boat ride from the city with a Traditional Owner-guided walk through the bush tucker-filled rainforest and visitation funds important Indigenous ranger projects.

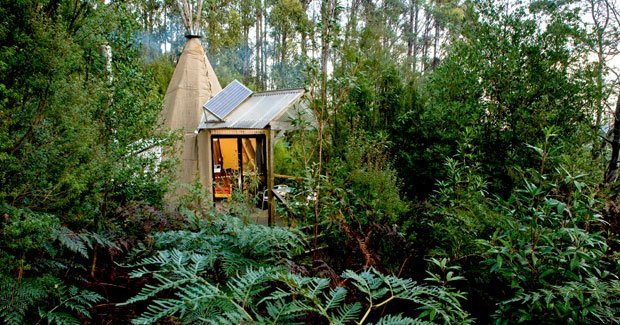

Even large city hotels are now expanding sustainable initiatives beyond merely offering to not wash your towels to ‘save the environment.’ Travellers can book a hotel that has reduced single-use plastics, through initiatives like swapping disposable amenities bottles for larger, refillable bottles and replacing plastic bottled water with filtered tap water. Some accommodation providers are supplementing fossil-fuel usage with solar, and some are utilising smart technology to save power, with sensors that power-down air conditioners when you step out of the room.

While there are many ways in which travellers and operators can tread more lightly on the planet and care for cultures, sustainability is a journey.

According to Penny Rafferty, any progress deserves encouragement, and positive or constructive feedback is always useful.

“Don’t let perfection be the enemy of good,” she says.

With the continued evolution of how we travel, maybe one day the term ‘sustainable travel’ won’t need to exist. Instead we’ll just have ‘travel,’ and its conscious nature will be implied.