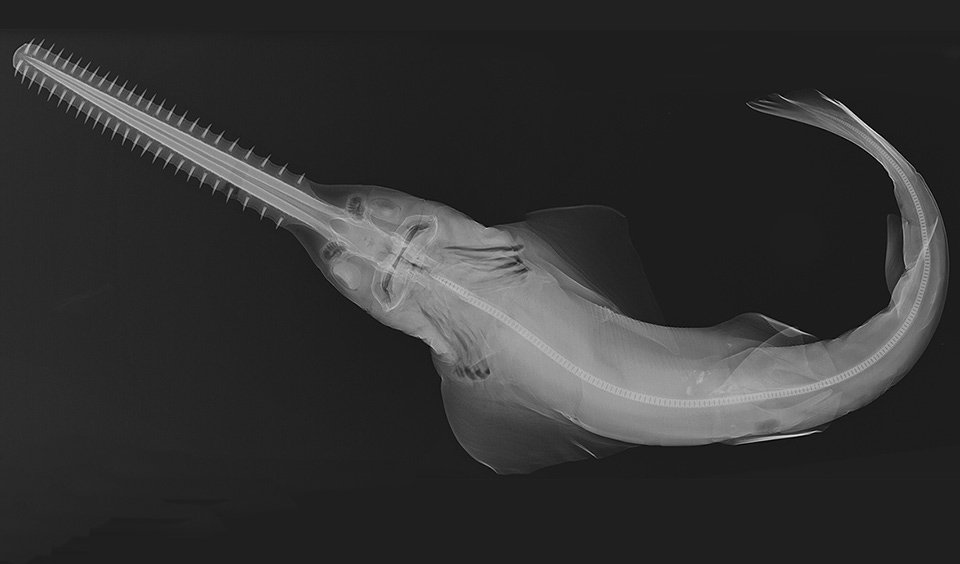

With shark-like bodies and elongated beak-like head projections bejewelled with razor sharp teeth, sawfish are unique.

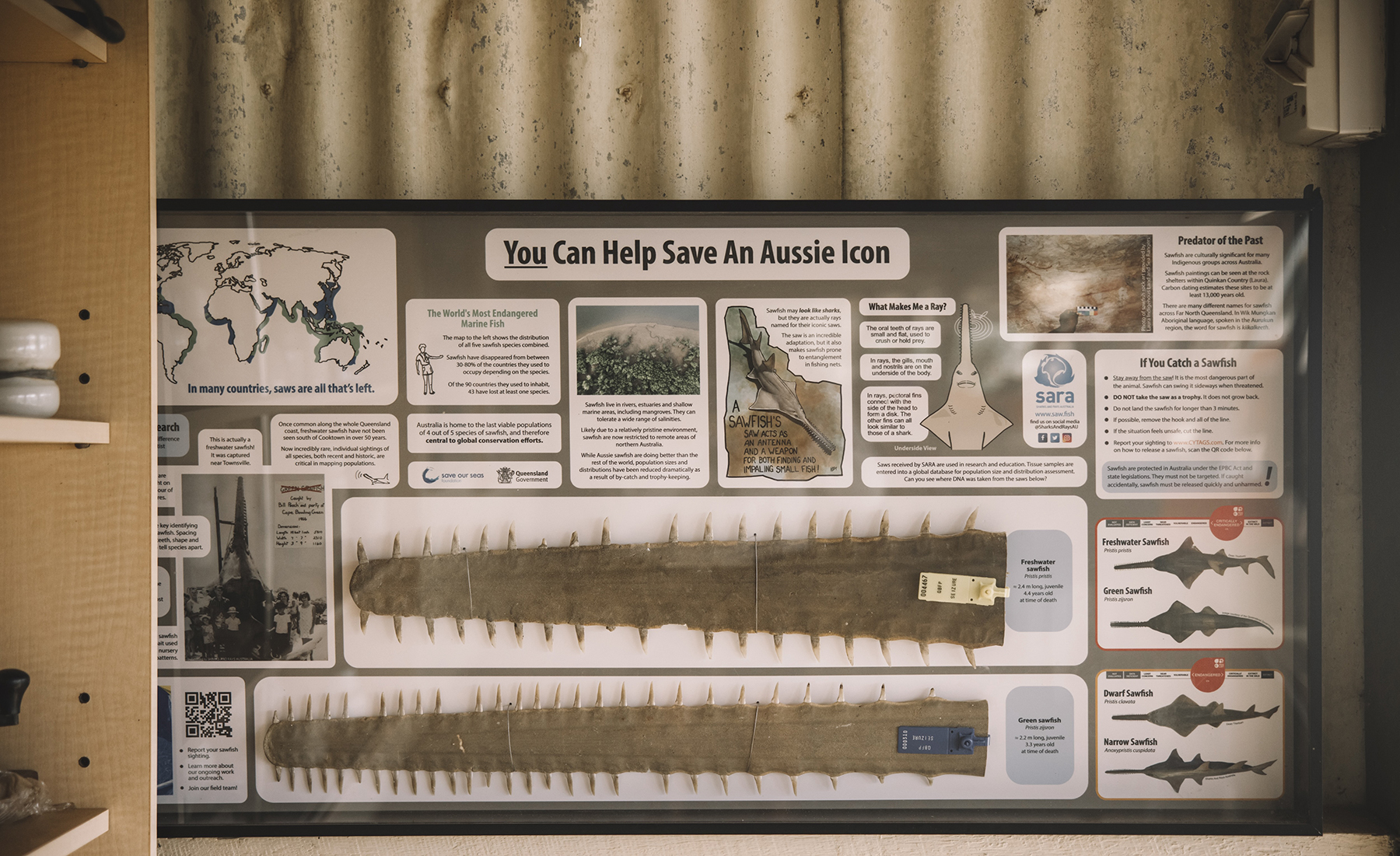

Fisheries exploitation, habitat loss, and trophy hunting (where the saws are hacked off for bragging rights and to be used as barroom curios) have seen all five of the world’s sawfish species – the green (Pristis zijsron), dwarf (Pristis clavata), freshwater (Pristis pristis), narrow (Anoxypristis cuspidata) and smalltooth (Pristis pectinata) – added to the IUCN’s global critically endangered list.

The warm coastal and estuarine waters of Australia’s sub-tropics and tropics are a stronghold for four of the five species – the green, dwarf, freshwater, and narrow sawfish.

But despite increased protection, these close relatives of sharks and rays keep turning up dead and their populations continue to decline.

In early 2023, four green sawfish were found near Karratha in Western Australia with their head projections known as rostra – the saws – hacked off. Later that year, in November, 17 freshwater sawfish were found dead, although not mutilated, on a WA pastoral station.

Queensland has also seen its share of dead and disfigured fish washed up on beaches, as well as saws being posted for sale online.

Now through a combination of citizen science and clever chemical analysis, researchers are using sawfish “trophies” to their advantage, in the fight to save these curious creatures.

Removing saws all but a death sentence

Zoologist Barbara Wueringer, a shark and ray expert originally from Austria who is an Honorary Research Fellow at Macquarie University, encountered her first sawfish in an aquarium. And it was an overheard conversation in another aquarium that sparked the idea for her PhD.

“I came across the fact that nobody had ever looked at why sawfish had a saw,” Dr Wueringer says.

“I was in, I think it was Sydney Aquarium, and there was a little girl there and she was like, ‘Mum, why do they have saws?’ Her Mum didn’t know.

“How can we have any knowledge about this animal if we don’t understand that adaptation?”

Through her PhD work she helped identify that saws have a dual purpose. Sensory organs known as Ampullae of Lorenzini and lateral lines located along the rostra can detect the movement of prey. The saw itself is also used as a weapon to subdue prey – usually fish in schools.

Removing the saw and releasing the animal alive is inevitably a death sentence.

Citizen science project ‘exploded’

During a field trip in Queensland’s gulf country in 2015, a chance encounter with an excited fisherman who’d just caught a saw-less sawfish led Dr Wueringer to the realisation that community outreach was needed, and that the saws were the key.

“That’s when I realised, we need to collect sightings from people,” she says.

Through her newly established research organisation Sharks And Rays Australia (SARA), Dr Wueringer launched a citizen science campaign, calling on the public to report sawfish sightings, incidental captures and even old family photos and saws in attics or on pub walls.

SARA began hosting events where the public could bring photos for ID, or even saws to be DNA tested and added to a database. Some people donated their saws to the researchers, and Queensland Fisheries [DAF] also donated confiscated rostra.

By 2019 SARA researchers had about 80 saws, which they DNA sampled and wanted to put to good use.

They came up with the idea to put them in display cases, with information about the species, how to report sightings, alongside their local Indigenous names.

As a SARA intern Veronika Biskis, with the help of a Save Our Seas Foundation grant, designed and built the displays, then coordinated their distribution to regions where they might have the most impact.

Today, almost every pub and tourist centre on Cape York has a sawfish display, Dr Wueringer explains.

From there, she says, the citizen science campaign took off: “That’s where it really just exploded. It went Australia-wide.”

Unlocking secrets in the teeth

Fast-forward to 2023 and Dr Wueringer publishes a research paper based on information gathered from more than 700 rostra from across Queensland, taken from fish between 1920 and 2020. More than 90 per cent had been captured in commercial gillnets.

Dr Wueringer and her colleagues found that within their samples, there were no freshwater or dwarf sawfish taken on the east coast after 2000. Just as concerning, the southern distribution of green sawfish, which can grow to more than 6m in length, had severely contracted.

The researchers also found that the overall size of the sawfish “trophies” being caught was shrinking.

The data was often based on the self-reported catch location of animals provided by fishers, meaning it could often only pin down the location to a general area.

But location data is extremely important for sawfish conservation. A paper by Murdoch University researchers, published this year in Aquatic Conservation, found that green sawfish return to their birth sites to reproduce, and males also don’t disperse far over the long term.

The next step is to narrow down exactly where sawfish travel to and reproduce. To do this, researchers are using sawfish teeth.

Sawfish teeth grow in size throughout the lives of these animals, adding new layers and entraining environmental fingerprints along with them.

Former SARA intern Veronika Biskis, now a PhD student at the University of the Sunshine Coast, is aiming to read those signatures to reveal the location of animals when each layer was put down.

In doing so, she hopes to reveal a much more precise map of where sawfish historically occurred, and where they are found now. This in turn, Ms Biskis says, can support focussed conservation efforts.

“Studies have shown the females return to the same river mouths to breed,” she explains. “If you remove them from that estuary, it’s likely you’re not going to see them again.”

That has already happened around large stretches of Australian coastline.

Ms Biskis’s data is yet to be published, but she says one thing it shows is that the green sawfish range, which once extended down the east coast to Sydney, has retracted to Mackay in central Queensland.

Glimpses of hope as laws and attitudes shift

The news hasn’t all been grim for sawfish researchers.

In June, Laura and Rinyirru Land and Sea Rangers captured a 140cm freshwater sawfish – a species thought to be extinct on the east coast – in Rinyirru (Lakefield) National Park, in Queensland’s Cape York.

They tagged the fish so its movements can be tracked.

Ms Biskis believes that, in part thanks to community outreach, attitudes towards sawfish conservation are changing.

With gillnetting being phased out in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area by 2027, she thinks we should see some recovery again in Queensland waters.

“I think we’ll see it sooner for [the narrow sawfish] because they reproduce at an earlier age,” she says.

“Green sawfish are still present in some areas down the east coast but there are a lot of gaps in that distribution that I’d love to see fill in.

“And then freshwater sawfish, they’ve got that one spot up there on the east coast… hopefully years down the line we can see them a little further south.

SARA has a portal on its page for the public to report sawfish sightings, accidental captures, saws, or photos. It’s promoting a national sawfish week in October for the public to contribute to the citizen science effort.