Any athlete at the Brisbane Olympics in 2032 who sleeps through their alarm and realises with growing panic they’ve only minutes to navigate the city’s rush hour to get to their event may not be in quite as much strife as they fear.

Just a few moments away from the Olympic Village there could well be a helipad-like area where a small electric aircraft will be waiting to rush the athletes to the track in time for the starter’s gun. And it won’t have a pilot.

Four-seater driverless air taxis will take off and land vertically and are the brainchild of the powerful South East Queensland Council of Mayors, which is already negotiating the purchase of the taxis from a US manufacturer.

By then, the Northern Territory Air Services will be ferrying tourists between Darwin and Uluru using 20 battery-powered, nine-seater charter planes and Sydney Seaplanes passengers will be silently whisked over the shimmering harbour by the nation’s first fully electric fleet.

“We believe there will be a revolution in aviation, and we want to be at the forefront,” Sydney Seaplanes CEO Aaron Shaw declares on the company’s website.

Some 15 years after the first Tesla reached these shores, airlines are finally waking up to the need to usher in a new era of environmentally friendly travel, with biofuels, energy-efficient planes, huge carbon-offsetting projects, electrification and even the tantalising prospect of hydrogen engines.

All the major carriers are spruiking their existing green credentials and making ever more ambitious commitments to strive for eventual carbon neutrality.

But just how much actual progress has been made so far? And can air travel ever become a truly sustainable way to travel, even with all the shiny new innovations?

A billion tonnes of carbon

It’s fair to say airlines haven’t exactly been model corporate citizens when it comes to the fight against climate change, and governments have done precious little to force them to change their behaviour.

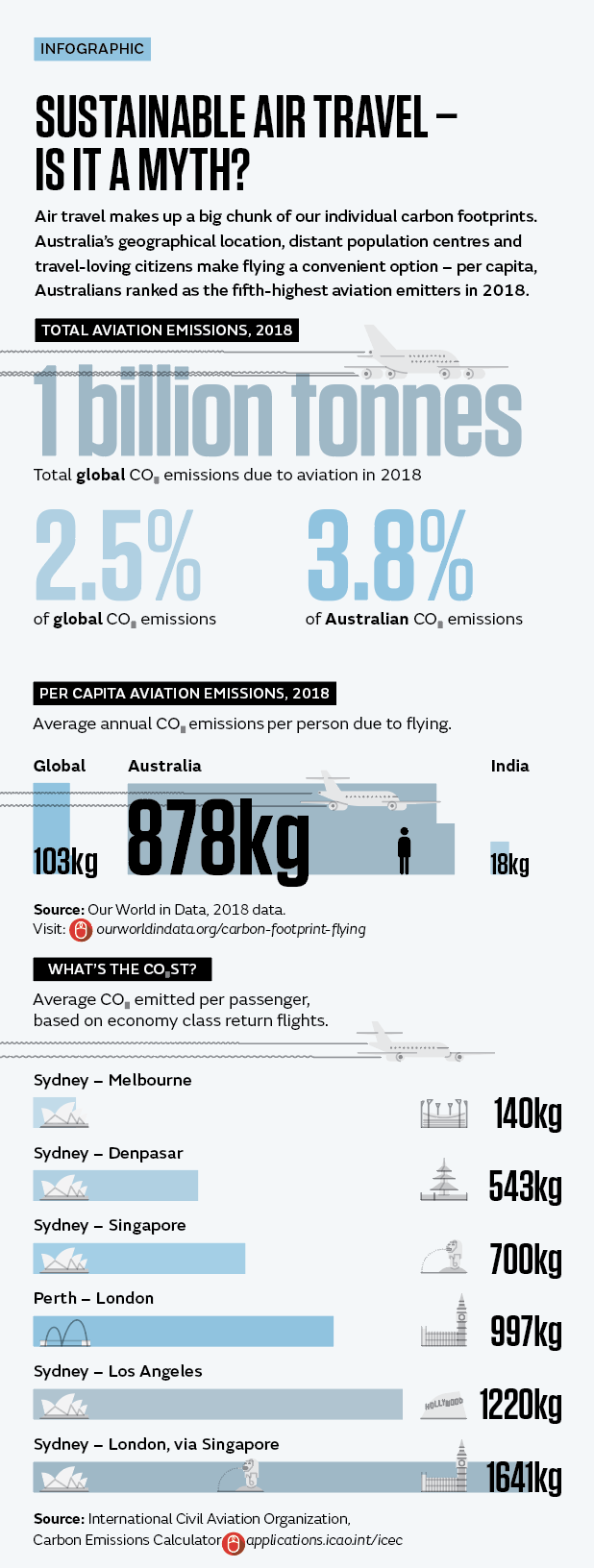

Aviation accounts for 2.5 per cent of global CO2 emissions (3.8 per cent in Australia) and causes 5 per cent of global warming. The amount of carbon the industry belches out shot up by 75 per cent between 1990 and 2012, and continues to grow. It reached a billion tonnes in 2018.

Even a return flight between Melbourne and Sydney generates 165kg of carbon per passenger – that’s more than the average person in some countries produces in a year. Between Perth and London, the figure is an extraordinary 5 tonnes, exceeding what an average individual emits in more than half the world’s countries. Or, to put it another way, a return flight for two people between Brisbane and Perth cancels out the benefits to the planet of a household recycling its waste for an entire year.

Flying business class doubles the damage caused. So, given that about 167,000 Australians take a domestic flight every day, on 1400 aeroplanes, it’s easy to see why reducing the industry’s weighty and dirty footprint has become so urgent.

Journeys by air pump out more CO2 per kilometre than any other form of transport, except perhaps Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin rocket.

The trouble with offsetting

Passengers wanting to fly in the most environmentally responsible way possible have to navigate their way through a bewildering barrage of misleading claims, questionable practices and some pretty blatant greenwashing.

By far the biggest culprit in this area is carbon offsetting, used by two-thirds of corporations claiming to be targeting net zero.

The way they work is that a company can pledge to cancel out the volume of CO2 it generates by investing in renewable energy projects or, more commonly, planting trees that will capture and store the noxious pollutants and pump out lots of lovely oxygen.

But numerous studies have found that most of the schemes used by airlines are unreliable and ineffective, with few checks and balances in place. And promising to plant millions of trees means you don’t actually have to cut emissions at all to reach sustainability targets.

In fact, it’s estimated that the total amount of land globally that would be suitable for tree planting is only 500 million hectares – much less than all the various tree-planting offset schemes are promising to reforest. Shell’s pledges alone amount to 50 million hectares!

Meanwhile, all Qantas passengers are offered offsetting from as little as $2 for a Sydney to Melbourne flight, but in 2018 only 1.1 per cent of emissions were offset.

Planting ever more trees and hoping for the best cannot be a long-term solution, according to best-selling author of Will Sustainability Fly?, Walt Palmer, himself a former pilot. “Offsetting instead of emitting less isn’t the way to sustainability,” he says. “Aviation has to get there in real terms, on its own, and there will be a lot of elements to that transition.Aeroplanes built in the short- to medium-term will all burn kerosene for decades, so the most significant breakthrough in the next few years will be policy that makes sustainable fuels financially feasible. Change has to happen fast, but if policy at both the national and international level doesn’t assist, it won’t happen.”

Which flights are most sustainable?

It may be decades before we can jet off for a guilt-free break that doesn’t hurt the planet, but there are still ways for air passengers to make a difference today.

Fly direct: Take-off and landing are both fuel-guzzling stages of any flight, so limit stopovers.

Choose your offsets wisely: Investigate a carbon-offset scheme before you hand over your cash. Those investing in renewable energies are more effective than the ones that just plant trees. There’s more information atgoldstandard.org

Find a low-emissions airline: German climate-protection group Atmosfair publishes indexes of the most fuel-efficient airlines for short- and long-haul flights. In their most recent survey, the best performing carriers included LATAM Airlines, Air France and TUI Airways. Out of the 60 airlines studied, Virgin Australia ranked 18th and Qantas 49th.

atmosfair.de/de

Go economy: Business class may be more comfortable, but you’ll feel decidedly uncomfortable when you realise your emissions have doubled.

Avoid night flights: When it’s dark, the contrails that aircraft leave behind them contribute twice as much to global warming. Winter trips are bigger polluters than summer ones.

Infographic by Mike Rossi

Towards net zero

The Swedish government has pledged all domestic flights will be fossil fuel–free by 2030 and international routes by 2045. The UK aims to do the same by 2050. The plans rely on hydrogen, electrification and a range of biofuels made from vegetable oils, algae and household waste that produce 80 per cent less emissions. Hydrogen is certainly a cleaner fuel, but technical hurdles mean it’s unlikely to be powering commercial jets for several decades.

Qantas has committed to net zero emissions by 2050 through a combination of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) and more efficient aircraft. It has also capped future emissions to 2019 levels, a move few other airlines have followed. By the end of the decade, 10 per cent of its fuel will come from sustainable sources and its carbon footprint will have reduced by a quarter.

As things stand, flights powered by electricity have to be less than 1500km due to the weight of batteries. Sadly, four out of every five flights are longer than that.

Many scientists doubt that hydrogen will ever be viable for long journeys, not least because a large passenger jet would need four times the volume of fuel that planes use today. But aircraft manufacturers are ploughing billions into pioneering research to unlock solutions.

Airbus aims to use hydrogen propulsion to develop the world’s first zero-emission commercial jet by 2035. Boeing has spent more than a decade exploring fuel efficiencies, hybrid commercial airliners and liquid gas technologies. In January 2023, NASA announced it was handing the company $590 million to investigate lighter planes that use a third less fuel.

Rolls-Royce has used battery technology to create an all-electric aircraft, albeit a single seater. It’s now partnering with British low-cost airline EasyJet, and in 2022 claimed to have run the world’s first aircraft hydrogen engine.

Australia’s lack of vision

Sustainable air travel is still a long way off, according to Emma Whittlesea, program manager of the Climate Ready Initiative at Griffiths University in Brisbane.

“Aviation is one of the most challenging sectors to decarbonise,” she says. “And governments have failed to provide strong leadership to reduce emissions. Current efforts in Australia are insufficient; we lack a clear vision, targets and strategic framework. A net zero target is only as good as the policies underpinning it.

“We need a complete transition away from fossil- and carbon-based fuel, which will require a transformation in how the industry operates,” she says. “There’s no single silver bullet solution, but with an injection of urgency, it could happen within the timeframes we need.”

She says biofuels can only be a stop-gap measure because even they burn carbon, and supply is still limited.