Imagine Australia without dung beetles. Put simply, we’d be drowning in poo. Australia has more than 500 native dung-beetle species, but they feast on marsupial poo, which is dry and compact. They don’t clear away large, moist cow pats – a huge problem, considering there are nearly 30 million head of cattle in Australia. The average cow or bull unloads up to 12 dung pads a day, and the accumulation can pollute waterways, foul pastures and encourage flies and parasitic worms by providing an ideal breeding ground. One large pad can produce 3000 bush flies in a fortnight.

Enter CSIRO’s Dung Beetle Program. Since the 1960s, scientists in Australia have been importing dung beetles to restore the ecological imbalance caused by European agriculture. It’s one of the great success stories of biological control, with 44 exotic dung-beetle species introduced into Australian ecosystems and 23 becoming established. By rolling and burying cattle dung, the beetles remove the breeding grounds of flies, aerate soil, and recycle its nutrients. The program claims to have reduced bush-fly populations by 90 per cent.

But introducing a foreign species into Australian ecosystems has hurdles. In a CSIRO laboratory at Canberra’s Black Mountain, entomologist Dr Valerie Caron is investigating dung beetles infected with a pathogenic fungus. The beetles are of the species Onthophagus vacca,which is native toMorocco and has no evolutionary defences against the pathogen that probably came from Australian soil. Known as the “icing sugar fungus”, its germinated spores form thick, white clumps that pierce the beetle’s exoskeleton. Enzymes and toxins produced by the fungus digest the beetle outwards from its internal tissues.

It’s been a long journey for these O. vacca beetles, which were collected in Morocco, studied at a CSIRO laboratory in France and finally sent Down Under. After a stint in quarantine, harvested eggs were surface-sterilised and sent to mass rearing facilities across Australia. Now a robust population of the beetles is kept in outdoor cages at Black Mountain. The insects were about to be released into the field, when the fungus outbreak occurred. It’s the first time the fungus has been observed in dung beetles and the outbreak might seem insignificant to those outside entomology circles, but its implications are far-reaching.

Three species have been imported in the last five years for the Dung Beetle Ecosystem Engineers (DBEE) project and O. vacca is one of them. All come from Morocco and were chosen for their “activity peak” – the time of year when they’re most active. Different species have different activity peaks, but it’s typically during their breeding season.

“There’s never one dung beetle that is active throughout the year, so we select species depending on what gap we’re trying to fill,” Valerie says. “We want to make sure there’s enough dung beetles for any time of the year, for any geographic region, so we don’t have dung accumulating.” O. vacca is most active from spring to early summer. It’s medium-sized and creates tunnels, burrowing underneath dung to create a nest.

It’s not the first time entomologists in Australia have imported O. vacca. The species was introduced in the 1980s but failed to establish. The pathogenic fungus might explain why. “Establishment is always tricky,” Valerie says. “We’ve studied them as much as we can, but it’s hard to predict if they’ll thrive.” Slight variations in soil moisture, the wrong dung type and new predators such as ibises might affect a species’ success.

The odds look stacked against them, but these beetles pack big potential and Valerie is optimistic. “We put them in the field as healthy as possible [and] make sure there’s genetic variation in the populations, so some should be able to survive those challenges,” she says. “We are hoping it can, as a species, evolve enough immunity to survive in local conditions.”

The DBEE project, supported by Meat and Livestock Australia, was preceded by similar strategies in 2014, 2011 and the 1990s – the latest in a chain spanning six decades, beginning with CSIRO’s 1965–85 Dung Beetle Program. The man behind the inaugural project was the late Dr György (George) Bornemissza, a Hungarian entomologist who arrived in Australia in 1950. Mention his name and Valerie becomes animated, describing him as “dung beetle royalty”.

“I joined CSIRO five years ago to work on dung beetles, and one of the things I like most about this project is the legacy,” she says. “It started in the ’60s with George, and now there’s me and our team here that keep it going. It’s a privilege as a scientist to be working in such a long program. We always feel like we have big shoes to fill.”

Born in Hungary in 1924, György Ferenc Bornemissza spent his youth collecting beetles in the forests of his home town of Baja and volunteering at natural history museums. He studied science at the University of Budapest and in 1950 received a PhD in zoology at Austria’s University of Innsbruck. Hungary’s communist regime emerged while George was studying abroad, so he migrated to Australia. He arrived in Fremantle in Western Australia on 31 December 1950, aged 26, and a few months later secured a position as a graduate assistant at the University of Western Australia’s Zoology Department.

George quickly recognised that Australia needed dung beetles. The accumulated dung fouled pastures and cost farmers millions of dollars to control the resulting flies, which were linked to livestock diseases such as bovine ephemeral fever. To George, these two issues had one simple solution: bovine dung beetles.

In 1955 he joined CSIRO’s Division of Entomology as a research scientist. It would take several years for his idea – to introduce exotic dung-beetle species into Australia – to gain traction within the agency. Funding for his Dung Beetle Program was approved in 1965, by which time George had authored scientific papers and was emerging as an authority in his field.

In a pilot project in 1966, George travelled to Hawaii to collect the eggs of seven dung-beetle species. Several generations were bred and quarantined before their descendants were released onto some cattle properties in Queensland in 1967. The project was a success and gained momentum. By the mid-1970s, research stations had been built in Pretoria in South Africa and Montpellier in France. In 1973 George received the prestigious Britannica Australia Award gold medal for his “application of ecology for human benefit”, the first of many honours and accolades he received, including a Medal of the Order of Australia in 2001 and the 2008 Conservationist of the Year Award from Australian Geographic. At the project’s conclusion in 1985, more than 1.7 million dung beetles had been released in Australia. George had identified nearly 150 dung-beetle species from 32 countries and imported

55 of them.

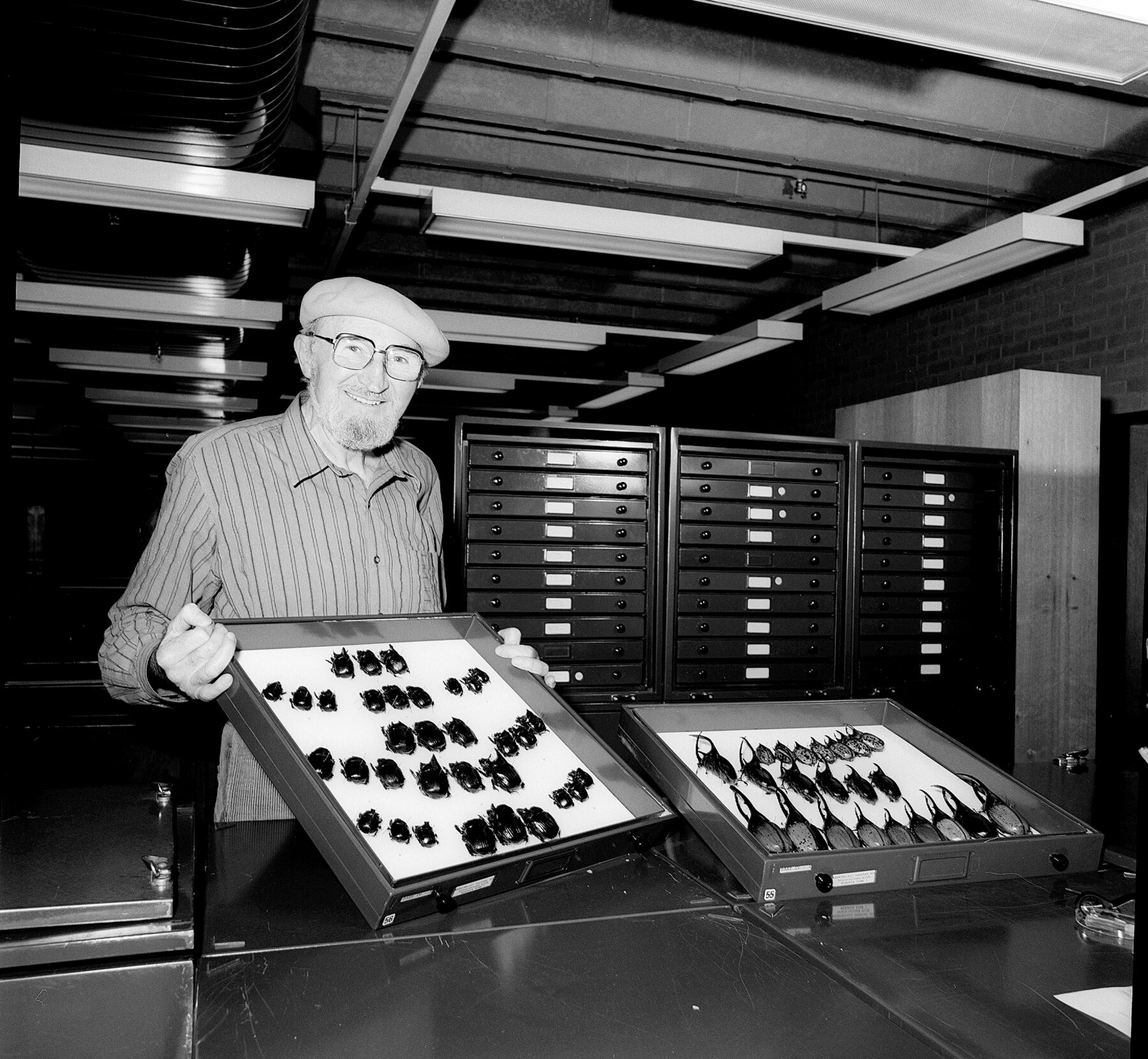

George retired in 1983 with worldwide connections, a suite of awards and an enormous insect collection. He settled in Tasmania and began producing display boxes of pinned beetles, which he donated to the Australian National Insect Collection in Canberra and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. It was his mission to educate people about the beautiful diversity of beetles across the world and their ecological importance, and raise awareness about the impact of habitat destruction. Arguably his most ambitious project was his Forest Beauties of the Beetle World collection, which featured specimens from the world’s six zoogeographic regions. Originally conceived as a 30-box display, it soon surpassed 100. One box took roughly 50 hours to complete, because the specimens needed to be relaxed, dried, posed and pinned.

“He worked on this 8–10 hours a day,” says amateur collector and close friend Mike Bouffard. “It’s the only thing he did, he had a real passion for it.”

Mike Bouffard met George in 1994, when he received an unexpected phone call from the decorated entomologist. George asked if Mike knew who he was – Mike did – and why hadn’t he reached out to him yet? “I was surprised someone of his stature would take an interest in my collection,” Mike says. When they met a few days later, George was impressed; Mike’s collection had two specimens of a species he’d never seen before. It was the start of a 20-year friendship. They began collecting together, combing Tassie’s Geeveston forests in search of Mt Mangana stag beetles, which George used as collateral to trade with German and Japanese collectors for his Forest Beauties collection. “There’s not a lot of insect collectors here in Tasmania, so we had the field to ourselves for quite a while,” Mike says.

George was absorbed by his work and completed the Asian, South American and African display boxes of his collection. He continued working after his dementia diagnosis, enlisting Mike’s help as a pinning specialist. Although a retired high school science teacher, Mike had taken entomology courses

at the University of Vermont in the USA, under the late

Ross T. Bell. George quashed the US influence and instructed him in the “European style” of pinning.

By 2012 George’s condition was deteriorating. He entered a nursing home and abandoned the project. Despite his steadfast commitment to his work, the Austral-Pacific and Palearctic boxes were unfinished. He died, aged 90, on 10 April 2014.

“When George died, there were so many insects left in the house,” says his widow, Jocelyn Bornemissza. “I said to Mike, ‘Do you think we should try and finish these beetles off?’ We decided to have a go at it, but we’d do it in our style, which was different from George’s work, and make it a tribute to him.”

As a retired artist and art teacher, Jocelyn had a different skill set that complemented Mike’s science background. “Jocelyn has the eye for colour, I have the eye for insects,” Mike says. “We’re a great team.” They spent the next eight years finishing the last 16 boxes – each taking about 50 hours.

George’s designs were traditional, displaying the beetles fanned in neat rows. Jocelyn’s designs were more experimental: beetles from cold climates arranged in snowflake patterns; desert regions depicted as cactuses; and specimens from Californian forests – famous for giant redwoods – were Christmas trees. “The designs were my idea. Whether George would’ve approved of those I don’t know – probably not!” Jocelyn says, laughing. “But we were quite pleased with our efforts.”

The duo finished the display boxes in early 2023. They’re now working on an exhibit of dung beetles for Pooseum, the quirky science museum in Richmond, Tasmania.