Just as naturalist Charles Darwin famously observed that the Galápagos archipelago’s finch species differed from island to island, the snails in an area of the Kimberley region in WA have evolved in response to distinct and isolated environments – on islands and in remnant rainforest patches. The landscapes where they occur – in Wunambal Gaambera Country in the Kimberley’s north-west – are arguably more dramatic and remote than the Galápagos’s finch habitat. They’re in a rugged, rock-strewn region 500km north-east of Broome, accessible only by four-wheel-drive. In the Dry, intrepid travellers along the Gibb River Road here make a side-trip to see the spectacular Punamii-Uunpuu (Mitchell Falls). Offshore, boat owners and luxury yachts are familiar with only a few of the hundreds of islands, resembling small jewels in an azure sea, that form the area’s Bonaparte Archipelago.

The region is already renowned for its high diversity of mammal species, including the world’s tiniest marsupial – the monjon. Yet, for every different mammal here, there are dozens of snail species, and although smaller and perhaps less charismatic, they’re just as scientifically important. Many of the snail species survive in very restricted habitats. Some are unique to their own small rainforest patch or, in the case of offshore locations, found only in a single spot on a particular island.

It’s the remarkable land snail diversity that has prompted this part of the Kimberley region to be placed on the National Heritage List. Most of the rare snails are members of the Camaenidae family – known for its remarkable diversity related to lifestyle. Embedded in their varied shell shapes, DNA, and even genitalia, is a story of adaptation – of evolution by natural selection.

“The feat they’ve accomplished is to adapt to drying conditions and find solutions in adapting both anatomy and behaviours to inhospitable conditions,” says Frank Köhler, a principal research scientist and snail expert at the Australian Museum. “Australia is an ancient continent that’s been isolated for about 90 million years. It was [once] a much wetter place than it is today, covered largely in lush and wet forests. Snails thrived in those moist conditions.”

Ancient forests expanded and contracted from the early Miocene period 20 million years ago, when the climate was warmer and wetter. It was followed by ice ages, when conditions became cooler and drier and sea levels fell. Kimberley land snails survived and evolved in the face of these climatic shifts, living in remnant habitat on rock faces or in rainforest leaf litter as a cryptic part of the ecology.

“You can read by their shell shape how they adapt to conditions,” Frank says. “To escape heat and sunshine, the best thing is to crawl into narrow crevices. But you have to be extremely flat-shelled to do this, like Torresitrachia [a Camaenidae genus that only occurs in Australia]. If no rock surface is available, snails tend to have large round shells – a circle has the best volume surface to prevent desiccation – and they bury into the loose sand.

“The rainfall pattern is reasonably predictable, so, being large and round, you can retain enough liquid to survive for six months until it rains.”

The result has been an extremely high level of endemism – many species that occur only here and nowhere else. “Species are basically found only in very small pockets, and 20km away you often find another species has replaced it,” Frank says. “By studying all this, we can learn a lot about how climate change over millions of years can shape biodiversity.”

The publication of a series of papers on Kimberley land snail diversity has recently been completed after years of painstaking work by Frank and others based on samples collected during expeditions late last century and early this century. The first of these was during the late 1980s, when scientific teams explored Kimberley rainforest patches. A second series of six expeditions took place on the region’s island chains between 2006 and 2010.

“I remember doing the surveys with the scientists on the islands,” says Jeremy Kowan, a Traditional Owner (TO) and ranger for Wunambal Gaambera Country. “We were turning over the rocks, looking for the snails. It’s good to see we can now describe them and that they are so important for our Country.”

Desmond Williams was another TO on the project – he assisted the hunt for snails with shell diameters from 3mm to 30mm. “The snails were right into the rocks and thick scrub on my grandfather’s Country,” he recalls. “There was easy access from the beach, but it’s pretty rugged country and there were prickly vines.”

The Wunambal Gaambera words for land snail are yabuli and nyaliga. Desmond says his people are familiar with the rock crevices where snails hide to escape heat and conserve moisture until the wet season, or wunju, arrives. He says bowerbirds often collect the shells to decorate their bowers. TOs themselves use larger snails for bait when fishing at freshwater spots.

The 1987 rainforest survey was a notable collection bonanza: more than 29,000 specimens of land snails, representing 115 species, about 100 of which later proved to be new to science. WA government scientist Norman McKenzie, who participated in the rainforest surveys and later island expeditions, recalls working alongside the late Geoffrey Mangolamara, a respected Wunambal Gaambera TO in the late 1980s. “Geoffrey made sure we were doing everything correctly when we were on Country, and he told us where the best spot to land our helicopter was,” Norman says. “He made sure we were across all the right cultural protocols to respect Country and Culture.” Norman says that in several rainforest locations, up to 20 snail species were found in a single stand. With more than 6300 rainforest patches in Wunambal Gaambera Country alone, it’s likely more species are waiting to be discovered.

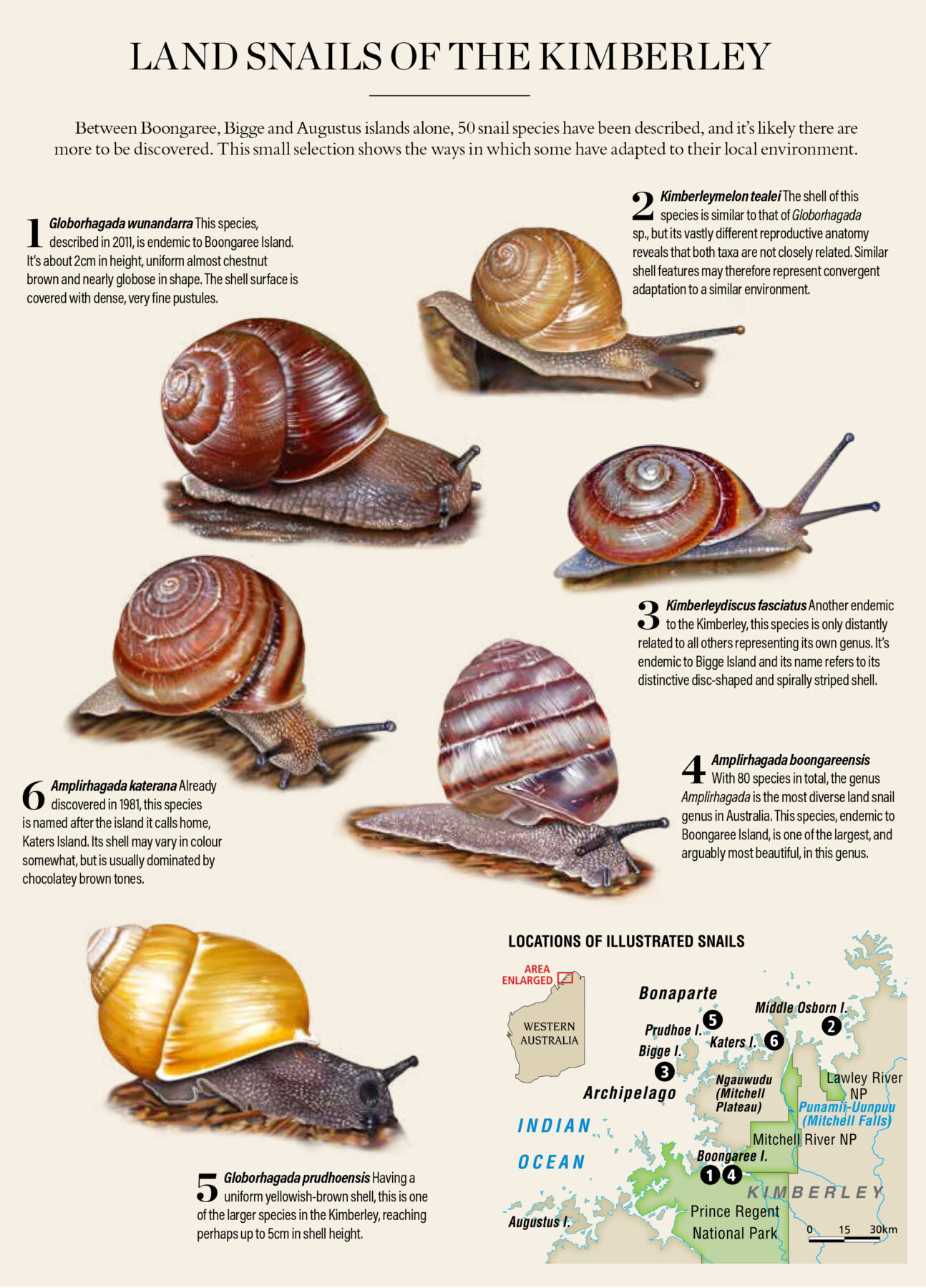

The later island surveys, which targeted 22 islands, identified at least 50 more snail species. One of the larger islands, Boongaree, is home to 13 camaenid species, including Globorhagada wunandarra, which Frank named after the Wunambal place name. Another eye-catching snail species, with “a large, highly turreted, almost trochiform shell with regular axial sculpture”, Kimberleymelon tealei,is found only on Middle Osborn Island. Frank’s favourite snail, Ampliragada boongareensis, “has a very pretty turreted shell”.

The snail work has brought together Bush Heritage Australia, Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation (WGAC)’s local Unguu ranger team and four other Kimberley native title groups. “Money was allocated for each island expedition team to have TOs working with the scientists,” explains ecologist Tom Vigilante, who is seconded from Bush Heritage to work alongside TOs.

“My job was to get people on the helicopters,” he says. “It was quite a challenging exercise, getting permission for the right people to go to certain islands, plus people camping out in basic conditions and everything needing to fit on a helicopter!”

German-born Frank Köhler had just arrived in Australia in 2008 when he was invited to join an island survey. “I came from a densely populated European country and then I jumped into this ancient, alien landscape – almost as alien as being on the moon.”

He could hear a crocodile bellowing one night, and the next morning was shown tracks in the sand that indicated the creature was large, and had come uncomfortably close.

“I opened my tent flap one morning and a snake was coiled up in front,” Frank recalls. “I wasn’t sure what to do, so I called out to the herpetologist on the team. He laughed and said it was only a python. But I wasn’t going to risk being bitten when we were hundreds of kilometres away by helicopter to the nearest hospital!

“It was all new for me, but fascinating – sandy, rocky islands with vine thickets, and walks into little gullies and crevices to try and find the snails. I was a novice to anything Australian, and it was a remarkable insight to hear from Aboriginal people about how they utilise the landscape – they’ve lived for thousands of years in relative harmony.”

Frank’s scientific research required dissection of snail genitalia. The Kimberley snails provided several surprises, he says. “The reproductive organs are incredibly big compared with body size; a bit like a human having reproductive organs the size of a big sack of potatoes. The organs are easy to find, and you slowly separate them from other organs and pin them out under the microscope. In the case of the Kimberley species, we found very strong differences in the reproductive organs, which suggest that these anatomical differences have almost a function like a key-lock mechanism to prevent mating between different species.”

Frank has devoted several years to Kimberley snails, yet the creatures have inflamed scientific passions for decades. One dedicated American, the late Alan Solem, invertebrate curator at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, travelled to Australia for the first rainforest survey on the Ngauwudu (Mitchell Plateau), but ill health prevented him from continuing. It was taken up by a Darwin-based collector, Vince Kessner, who assembled and labelled 27,000 specimens and sent them to Alan.

“I had the honour to complete Alan Solem’s work after he died,” Frank says. “The island surveys have added at least another 50 new species. They are pretty stunning numbers. Many of these islands are small, only 2–3km in diameter, and Boongaree, Bigge and Augustus Islands each had 15 to 20 species, so that’s 50 for three islands alone.

“There are many more species that await discovery, and I’d leap at a chance to go back.”

So, why should we care about the fate of a humble snail? Norman says many of the snails have already been listed as threatened “because of their short range and fragility to too-frequent burning, which wipes out populations. When you’ve got a whole species restricted to one little outcrop 100m across, it naturally becomes a candidate for being listed,” he says.“This research is the basic coinage of environmental protection, and it’s read by the relevant consultants. If you’re going to protect the evolutionary process of these land snails, you need conservation protection over those islands.”

The extraordinary science findings have been noted by other Indigenous communities, some of which have adopted the Wunambal Gaambera’s Healthy Country program. The 10-year plan, directed by Elders and instrumental in managing the island survey work, has now been modelled in 30 Healthy Country plans elsewhere in Australia.

“We were surprised that everybody wanted a piece of our Healthy Country program,” says ranger Desmond Williams. “Our Country is all healthy, all good.”

Tom Vigilante says a future goal for the next Healthy Country 10-year plan is to protect species-rich habitats. “The Galápagos is where Darwin got his ideas about speciation, and although it’s not exactly the same, we have shown there is huge diversity on islands and in rainforests. We still do work on the islands, and there’s a whole lot of smaller ones that haven’t yet been surveyed,” Tom says.

“The snail story has taken a while to come out, but it shows why we need to manage threats – like fire, pigs and weeds – to our islands and rainforest patches.”