“It’s an absolute crisis…a source of national shame!” Professor Chris Dickman says in frustration as he leans across his desk at one of Australia’s oldest scientific institutions, the School of Life and Environmental Sciences at Sydney University.

Chris is an old-school academic – highly esteemed, with a worldwide reputation in his area of expertise built during a career that’s spanned more than three decades. He’s very much a man of science who prefers to air his opinions via peer-reviewed research published in highbrow journals.

But the softly spoken, usually mild-mannered, world-leading ecological scientist is angry and, in fact, deeply saddened that parts of Australia have been losing native forests and woodlands at extraordinary rates. Clearly, Chris says, we haven’t learnt from past failures to protect our forests, and the potential consequences for Australia are huge.

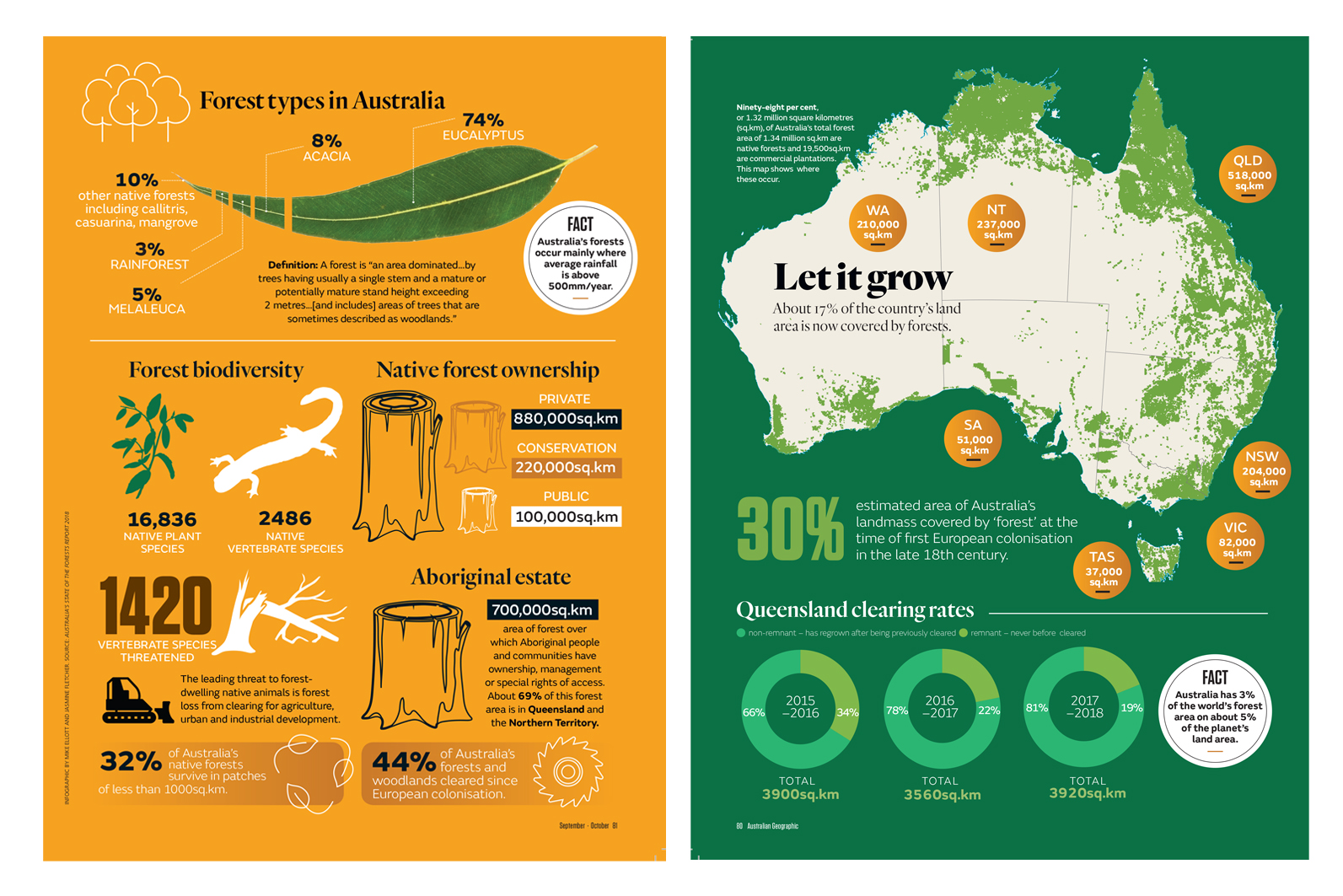

It’s not as if modern Australia ever had a lot of trees to lose in the first place. The continent was once covered with forests but that was in the distant geological past. Tree coverage has slowly been receding naturally during the past 5 million years as the climate in this part of the world has dried. By the time of the first European colonisation here, little more than two centuries ago, mainland Australia was mostly desert and arid habitats with only an estimated 30 per cent covered by forests and woodlands.

Today, that’s been almost halved, due to the broadscale clearing of trees partly to make way for urban and industrial development, but mostly for agriculture. That we’ve lost almost half our forest and woodlands in just two centuries is a confronting statistic, but it’s largely a historic legacy. Much of the clearing occurred through the 19th century and first half of the 20th, when environmental considerations came second to putting food on the table. It was when our European forebears didn’t know any better; before we discovered that most species living in Australia’s forests occur nowhere else on the planet; before science showed that healthy forests protect soils and waterways, reaping multiple economic, environmental and social benefits; and it was well before the realisation that trees are an outstanding place to safely lock away carbon from the atmosphere, where it’s wreaking havoc with the planet’s climate.

And yet, in recent years, deforestation has been proceeding in some parts of Australia at rates claimed to be among the highest on the planet. It prompted Chris and more than 300 of his colleagues across the nation to release a joint declaration in March through the Ecological Society of Australia calling for stronger laws that would restrict the clearing of stands of native trees.

Western Queensland and north-western NSW are the main epicentres of Australia’s deforestation activity, most of which is to make way for pastures to run livestock, and, in both states, it’s been facilitated by changes in legislation.

The consequences of clearing forests and woodlands on the level that’s been occurring in Queensland and NSW are huge. The most direct effect is a large-scale loss of native flora and fauna. According to a report released late last year by World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), forest clearing kills millions of native animals a year in Australia. The report, on which Chris Dickman collaborated, estimated that 87 million animals, including more than 9 million mammals, would have died in NSW during the 17 years to 2015 due to the clearing of 5180sq.km of native bushland.

In Queensland, the woodland habitat most affected by clearing has been brigalow forest. Brigalow is a type of wattle that grows about 20m tall and forms dense stands. Because pastoralism came to western Queensland much later than to the southern states, these forests were largely intact up until the 1960s. They originally covered an estimated 130,000sq.km of inland and eastern Queensland and north-western NSW but in the past six decades more than 90 per cent of this forest habitat has been cleared.

It’s estimated that brigalow forests can support as many as 1000 different plant species and provide niche habitats for a huge variety of specialist animals, including the bridled nailtail wallaby, black-breasted button-quail, northern hairy-nosed wombat, golden-tailed gecko and ornamental snake, all of which are now threatened and, in most cases, locally extinct in many areas where they once occurred. Former brigalow forest animal species that are already totally extinct are the paradise parrot, white-footed rabbit-rat and Darling Downs hopping-mouse.

“Australian flora and fauna are highly endemic, particularly the vegetation, mammals, reptiles and frogs,” Chris explains. “If the habitat for these animals is destroyed, they’ve got nowhere to go. We’re the only custodians for most of these [woodland and forest species] and we’re driving them on an inexorable path to extinction. There are global, regional and local responsibilities for these habitats and I think much of that is being abdicated at the moment.”

Tied in with species’ loss are more widely felt impacts, including a suite of local ecological services that disappear with the trees. One is flood mitigation and there’s evidence the impact of the floods that hit towns in north Queensland, including Townsville, earlier this year, was worse than it should have been due to forest clearing.

Jelenko Dragisic, general manager of Greening Australia (GA) Queensland, warns it’s a sign of what can be expected more and more in the future with climate change. It’s imperative, he says, that the resilience of the Australian landscape is safeguarded and reinforced even further by protecting what tree cover we have and restoring what’s already been lost. GA has been one of the leading service providers working with landholders and local communities to help deliver large-scale landscape restoration projects across the country through the federal government’s 20 million tree project, which is due for completion next year (see Under the canopy, AG 147).

In a perverse irony, because it’s largely responsible for deforestation in the first place, agriculture suffers when the trees go. “For example, fully functioning woodland has a whole suite of insect species and many can be beneficial in terms of taking out crop pests,” Chris explains. Also among these insects are pollinators important for agricultural production.

In another example, Chris says there have been widespread impacts caused by reduced numbers of medium-sized marsupials, such as bettongs and bandicoots, in the dry country in western NSW, due to the removal of woodland habitat to make way for pasture for sheep. “We’ve got a thin layer of nutrient-impoverished soil across most of Australia and these marsupial species would dig in the topsoil and move it about, tonnes of it every year,” he explains. “It would mean it was easier for rainfall to infiltrate and get into the water table, rather than running off and taking the topsoil with it, as now occurs.” What these marsupial ‘landscape engineers’ did was reduce the chance of salination and encourage nutrient cycling. Pockets of organic matter would build up where these animals scratched in the soil, creating little beds of nutrients where plant germination could take place.

Then there are the big picture impacts of large-scale tree loss. Removing large tracts of woodlands or forests affects climate locally as well as further afield. Globally, that occurs through the release of carbon into the atmosphere when the trees are destroyed.

Locally, there can be reduced rainfall when large stands of trees are removed. This is because trees influence local water cycles by taking moisture in through their roots and releasing it through their leaves into the surrounding air. “So you’re much more likely to get an increase in the water cycle where you have trees, simply because of that throughput that occurs when rain falls,” Chris says. “The dry country is where so much of this devastation is happening. And to most people it’s out of sight and out of mind.”

With so much forest loss having occurred in Australia, saving or rehabilitating every last scrap is now being widely seen as imperative. “We now regard even a small patch of remnant woodland as being incredibly valuable because that’s refugia for species that are just trying to find homes and eke out a living in increasingly small pockets of habitat,” says Dr Rebecca Spindler, Bush Heritage Australia’s executive manager of science and conservation. The original intent of this privately funded, not-for-profit organisation formed in the early 1990s was to buy and protect good-quality native bush on private property. “But we found really quickly that we also needed to buy some of the areas where there should have been high biodiversity and start rebuilding that as well.”

To that end, one of the organisation’s most extensive and successful projects has involved restoring and reconnecting fragmented woodland habitats between the Stirling Range and Fitzgerald River national parks. It connects with Western Australia’s Gondwana Link project, which is aiming to achieve “reconnected country across south-western Australia, from the karri forests of the south-west corner to the woodlands and mallee bordering the Nullarbor Plain, much of which has been cleared for farming”. Bush Heritage’s work on the Fitz-Stirling mosaic of reserves will restore and reconnect fragmented habitats in this global biodiversity hotspot.

Rebecca explains that the current success of the Bush Heritage project offers hope for rehabilitating many of Australia’s already cleared treescapes. “Over the past 12 years we have helped rebuild connectivity in this area and we’ve seen birds come back that haven’t been seen for generations, including malleefowl,” she says. “But it’s a hell of a lot easier to stop it from going in the first place.”

Along with Bush Heritage there are many organisations now working to restore Australia’s lost tree coverage, including Landcare Australia, Greening Australia and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy. And there are also many projects at all levels of government, such as Queensland’s $500 million Land Restoration Fund, which supports carbon farming through various strategies, including by ‘protecting native forest by reducing land clearing’. “We’ve all got people on the ground working out the solutions [for Australia’s declining biodiversity] in the face of increasing threats from all over the place – climate change, invasive species, fire and an absolute barrage of land clearing,” Rebecca says.

The most promising projects are working across all forms of land ownership and that, of course, includes farmers, who appear increasingly to be the key to saving and restoring much of Australia’s forests and woodlands. “So little native vegetation in NSW remains in a healthy condition, and with 70 per cent of land in NSW privately owned or leased, the responsibility and opportunity to restore our degraded landscapes is in the hands of our farmers,” says Kate Smolski, CEO of the NSW-based Nature Conservation Council. “We need legislation that supports landowners to protect and restore forests and bushlands, not encourages them to clear it. In addition to strong laws protecting forests and bushland, landholders should be supported financially to protect and restore areas.”

Bush Heritage also sees farmers as critical to addressing Australia’s deforestation. “There’s already 54 per cent of Australia under grazing…making it a sector that conservationists can’t ignore,” Rebecca says. She explains she’s increasingly coming across farmers looking to find alternative ways of working.

Importantly, they’re wanting to source methods that are better suited to local conditions and not based on the higher, more reliable, rainfall and nutrient-rich soils seen in Scotland and England, upon which much of Australian agriculture has been traditionally based.

“We are now looking at more innovative strategies, working with agriculture to find a new way forward so people can have productive, profitable land, working hand in hand with conservation rather than the two sectors being in competition,” Rebecca explains.

She stresses that she’s not advocating the total de-stocking of Australia. “But I think there really is a middle ground; I think there is a way we can have productive animals on the country but do it in a way that is regenerative and make sure that we’re preserving biodiversity values at the same time,” she says.

And that’s exactly what a landmark pilot study recently run in NSW has found.

The title of the final report into the study released this year leaves little doubt as to what it was all about: Graziers with better profitability, biodiversity and wellbeing: Exploring the potential for improving environmental, social and economic outcomes in agriculture. And what it found is good news for Australian forests as well as farmers – that there could be huge gains, including financial, for farmers working their land in a way that supports biodiversity.

Supported by funding from the federal government’s National Environmental Science Program, the project looked at grazing in a region that once supported large tracts of box gum grassy woodlands, a type of habitat that has been listed nationally as threatened since 2010. Once widespread throughout south-eastern Australia, less than 8 per cent of the area originally covered by this type of woodland survives: much of it has been cleared for cropping or grazing or modified due to the addition of fertiliser to grow pasture for livestock.

The report compared outcomes for traditional farmers with those who identified as ‘regenerative farmers’, who’d chosen to retain box gum woodland on their farms and work around it. The idea for the project came initially from Sue Ogilvy, a former physics graduate and IT expert who is undertaking a PhD in environmental-economic accounting at the Fenner School of Environment and Society at the Australian National University. She was intrigued by the fact that although a huge range of quality statistics and facts were collected around farming in Australia, the importance of natural resources to agriculture appeared to have been overlooked.

She joined forces with Mark Gardner who’s been an agricultural consultant for more than 20 years in the Dubbo area, working with farmers in the sheep and wheat belt of western NSW. Between them, Mark and Sue enlisted an expert team of ecologists and economists. This included: economists with the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage; CSIRO’s Dr Sue McIntyre, the leading expert on Australia’s grassy woodlands; the University of Queensland’s Dr Thilak Mallawaarachchi, a leading agricultural economist in the Asia-Pacific; and Dr Jacki Schirmer from the University of Canberra who has been running a long-term wellbeing study in regional Australia.

Mark says many farmers want to look after their land for future generations in a way that supports the natural environment. But they often don’t know how to do it. “It’s the how-tos, the techniques, that require some examination, particularly in light of a more variable climate,” Mark explains. “The sorts of questions farmers are asking are: ‘Is there another way that we can achieve this desire of looking after our land and potentially handing it on?’ And it’s just that sort of question that our project has helped in a very small way provide some information for.”

Sue agrees it’s widely understood that natural resources are a very important part of agricultural production. “But we have not equipped our agricultural economic scientists with the resources to characterise them as a factor of agricultural productivity,” she explains. “So we had no statistics to tell us whether farms that had preserved grassy woodlands in good condition were more or less profitable than farms that had cleared them and converted them to exotic pastures.”

Particularly telling in the report was this statement: “We conclude that regenerative grazing can be at least as profitable, and at times more profitable, than other methods whilst maintaining and enhancing grassy woodland biodiversity on their properties.” In short, not cutting down the woodlands made for a better farm.

Mark says every farmer wants to leave their land in the best condition possible. Not so long ago that would, without question, have meant more introduced pastures and few trees. Now there’s a growing movement among farmers that means a farm with native trees, grasses and birds, as well as a profitable business.

“I think revolution is a strong word,” Mark says. “But I do think that there’s an absolute sea-swell of change in the farming community.”

Forest clearing: the legal landscape

Legislation protecting Australia’s forests comes and goes with changing governments.

Less than half of Australia’s remaining native forests are on government-owned land and the concept of legislation to control vegetation clearing on private properties can be unpopular with owners. Nevertheless, laws to control clearing have been introduced since the late 20th century because, as is now well known, natural vegetation has ecological functions that extend well beyond private boundary fences.

Most land clearing in Australia is covered by state laws. In Queensland, it’s controlled under the Vegetation Management Act, introduced in 1999 and progressively tightened during the next decade. But in 2012 the newly elected Liberal-National state government began winding back regulations in the Act. It cleared the way for bulldozers to take out large tracts of forests and woodlands that weren’t protected in national parks or other forms of reserve in the state.

As a result, tree clearing rose in Queensland by 73 per cent in 2012–13 from the previous year and “by a further 11 per cent from 2012–13 to 2013–14”, said the Australia State of the Environment 2016 report.

Queensland’s annual Statewide Landcover and Trees Study shows the destruction continued in 2015–16 when “the total statewide woody vegetation clearing rate was 3950sq.km/year…a 33 per cent increase from the 2014–15 [rate]”.

Clearing slowed slightly the following year but then in 2017–18 climbed again to 3920sq.km/year, close to the 2015–16 rate. About a third of land affected is what’s known as “remnant vegetation” – virgin bush, never before cleared.

There has, however, been some recent good news in Queensland. In 2015 the newly elected state Labor government foreshadowed a tightening of the Vegetation Management Act and in May last year eventually succeeded in restoring many of the regulations controlling tree clearing that had been removed by the previous government. Scientists are now waiting for confirmation from satellite imagery to show, they hope, that clearing in Queensland has now dropped to a more acceptable rate.

In NSW, recent legislative changes have been responsible too for a level of clearing that has also set alarm bells ringing with ecologists. In 2017 the NSW state Liberal government began a series of “reforms” that led to the repealing of the Native Vegetation Act 2003, Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, Nature Conservation Trust Act 2001, and parts of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. It introduced the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2017 and made amendments to the Local Land Services Act 2013.

In the wake of these changes the Nature Conservation Council (NCC) and WWF compared satellite imagery of the Collarenebri and Moree area in northern NSW from 2016, 2017 and 2018 and found the clearing of forest and woodland “almost tripled in one year following the repeal of the NSW Native Vegetation Act”.

Following the claim, the office of the NSW Auditor-General investigated and released a report in June on the impact of the legislative changes. It was damning: “The clearing of native vegetation on rural land is not effectively regulated and managed because the processes in place to support the regulatory framework are weak. There is no evidence-based assurance that clearing of native vegetation is being carried out in accordance with approvals. Responses to incidents of unlawful clearing are slow, with few tangible outcomes. Enforcement action is rarely taken against landholders who unlawfully clear native vegetation.”

It found the clearing of native vegetation on rural land had more than doubled from 2013–14 to 2016–17 and so too did the extent of unexplained clearing of woody vegetation.