Looking across the windswept plateau of World Heritage-listed Macquarie Island in December 2008, ecologist Dana Bergstrom realised something was seriously wrong.

“It was Christmas, and I was in alpine tundra,” recalls Dana, now head of Biodiversity Conservation with the Australian Antarctic Division’s Environmental Protection Program. “Everything should have been greening up. The cushion plants there go brown during winter, then turn green in spring–summer. But lots were still brown and some appeared dead.”

Individual Macquarie cushions usually live hundreds of years. It’s a keystone plant species on the plateau, meaning it’s integral to much of the life on the Australia-governed subantarctic island, located in the Southern Ocean, between Tasmania and the Antarctic continent.

Research by Dana and her island colleagues ultimately identified that protracted and unprecedented dry conditions caused by climate change were behind the demise of the cushion plant and the ecosystem it defined. “The plateau had been losing water in summer, with records showing that for 17 straight years more water was going out of its soil than was being replaced by rain,” says Dana, explaining that by the time moist conditions returned, disease had spread through the surviving cushion plants. Suddenly the species was critically endangered, and Macquarie’s scientists watched helplessly as the plateau’s ecosystem collapsed as a result.

Then came reports of something similar happening at Casey Station, one of Australia’s Antarctic mainland research stations. There, a collapse was also being seen, in the ecosystem based on moss beds – known as the Daintree of the South, because, like tropical rainforest, it supported a particularly high level of biodiversity. “Was this happening elsewhere across Australia?” Dana says was the obvious question.

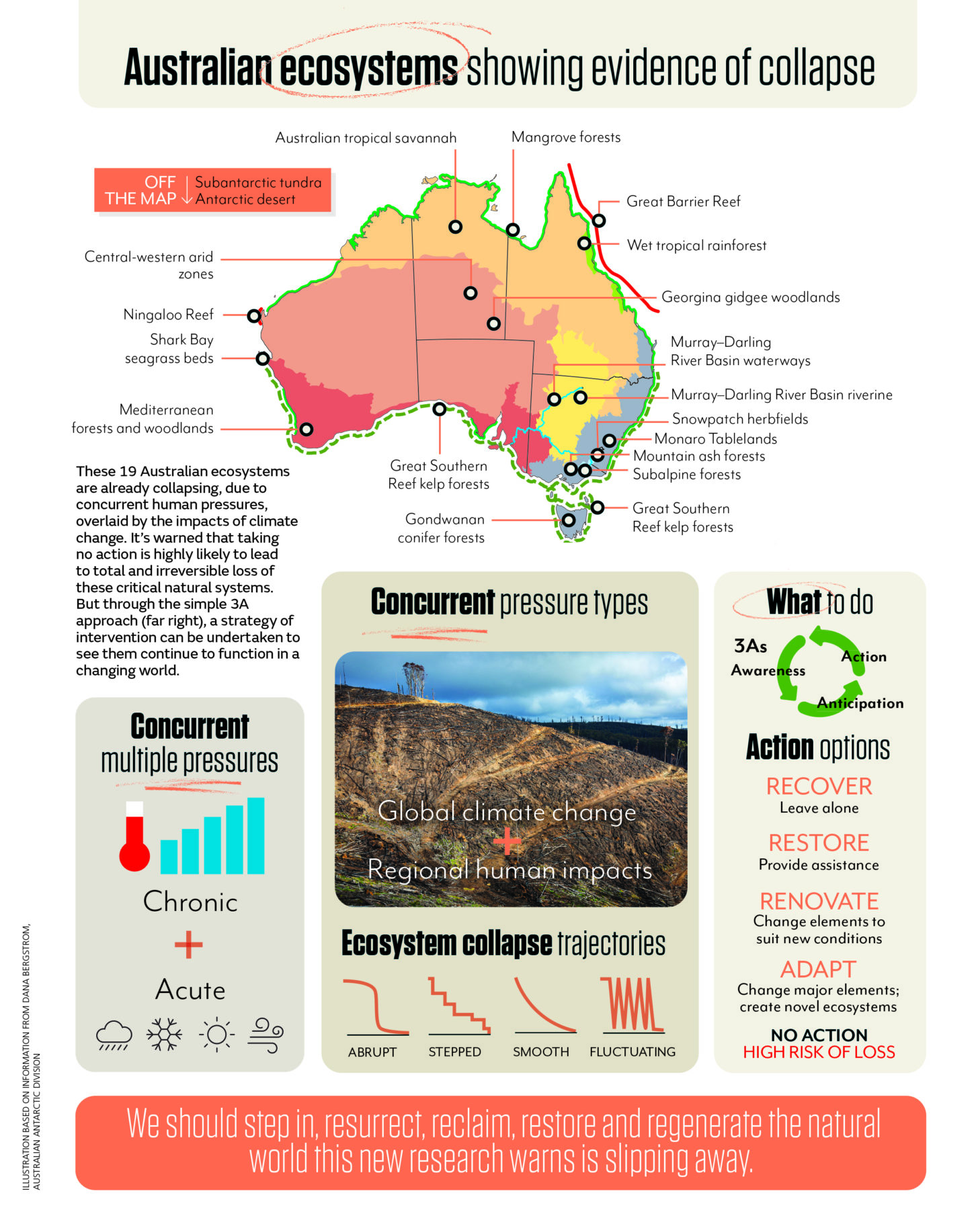

The distressing answer came last February via a scientific paper accompanied by a 101-page detailed report compiled, with the support of the Australian Academy of Sciences, by Dana and 37 other ecologists and climate change experts. Most have leading international reputations and together represent nine centuries of scientific knowledge. It’s an extensive and exhaustive work that identifies, along with the two failing Antarctic ecosystems, a further 17 examples that also suffered collapses in parts of their range at about the same time.

Some, such as the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), are well recognised. Others are more of a surprise. Ningaloo Reef off the West Australia coast is an ecosystem about which scientists have long had concerns, but the extent of its damage has not been appreciated until now. Also included are places such as the Georgina gidgee woodlands of Central Australia, which are not well known but are equally important.

There are multiple pressures behind the failure of these natural systems, ranging from habitat destruction and modification to pollution. But underpinning the demise of all of them are the impacts of climate change, notably, altered weather regimes.

The report, which took more than 18 months to produce, has shifted Dana’s perspective on conservation. When she was an undergraduate more than 20 years ago, she believed nature should largely be left to operate under its own laws – allowed to survive, or otherwise, without human intervention. She subscribed to the typical and widespread view of nature conservation at the time that protection through, for example, World Heritage-listing, or national park status, was crucial, but you didn’t interfere when a habitat was threatened by natural forces…even to save it.

“So if you were walking along the beach on Heron Island [off Queensland] and saw a turtle nest mistakenly breaking out of the sand at low tide, in the middle of the day, and none of the hatchlings stood a chance against the gulls swooping on them, you’d leave them alone,” Dana says. As tragic as it seemed, it was nature’s way. But these days the forces of nature aren’t so ‘natural’.

“So,” Dana agrees, “it’s time to change.” We should, she says, be doing what it takes to step in, resurrect, reclaim, restore and regenerate the natural world this new research warns is slipping away faster than anyone thought. We need to interfere, she says, and there’s an urgency to do so.

The paper is certainly a harbinger of doom. But it also carries a framework for solutions (see graphic, opposite), acknowledging that widespread rehabilitation and restoration can still help Australia’s struggling ecosystems. The traditional way to bring back many of these would be through the practice of ecological restoration, which is carried out according to rigid standards. But already modifications to the usual rules adhered to during this process are being needed for some ecosystems. One of the best examples is giant kelp forests.

Giant kelp, a seaweed species that can grow 35m tall – as high as a seven-storey building – once formed extensive underwater jungles in waters off Tasmania. “But unfortunately, we’ve lost about 95 per cent of that species in Tasmania, which is the heartland for giant kelp in Australia,” explains kelp ecologist Dr Cayne Layton, who’s based at the University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies. “So there’ve been really significant losses and those are due to ocean warming caused by climate change.”

Kelp forests are important to ocean productivity, because, like land forests, they support a huge range of other species. They provide critical habit on the Great Southern Reef for a suite of animal species found nowhere else in the world, including the weedy seadragon and Australian giant cuttlefish.

Cayne and his colleagues are desperately trying to salvage the almost-obliterated giant kelp ecosystem. Although what they are doing is ecological restoration, Cayne concedes it differs markedly from the traditional definition of the practice, which strives to exactly replicate and restore original systems. And that’s because the environment in which the giant kelp ecosystem used to exist has been fundamentally changed forever.

For a range of climate change-related reasons, such as shifts in wind and ocean circulation patterns due to warming water, the East Australian Current is getting stronger. It’s sending warm, nutrient-poor water further south than it used to, into places such as Tasmania, where it’s displacing the water that’s historically been there, water which, coming from the Southern Ocean, is cool and nutrient-rich.

“Now the whole of south-eastern Australia – from the bottom of New South Wales, along Victoria and to the east coast of Tassie – is considered a marine global warming hotspot,” Cayne explains. “We have become a window into the future for many places around the world. What we are already experiencing here now is going to occur elsewhere during the next few decades.”

A critical aspect of ecological restoration requires overcoming the initial driver behind the destruction. But what’s causing giant kelp loss is ocean warming, and fixing that is not possible in the short term. “So we are taking a bit of a roundabout approach, and instead of changing the environment to suit the kelp, we’re trying to change the kelp,” Cayne explains. “We’re looking within remnant populations of giant kelp for individuals that are naturally more tolerant of warm water.”

Cayne’s research team is identifying those plants, taking samples, breeding them up in high quantities in the lab and planting them back out in the ocean at three trial sites. One, in Trumpeter Bay on Bruny Island, has been selected by members of the weetapoona Aboriginal Corporation, which is sharing Indigenous knowledge of kelp habitat loss with Cayne’s group.

The project, Cayne agrees, is a stopgap, not a silver-bullet solution: “We’re transparent and honest about that, but these are the types of approaches we’ll need moving into the future. They’ll hopefully buy us time until we start to reduce carbon emissions, which is still the number-one priority. It’s critical to do this for these really important, iconic and globally unique habitats.”

Similar research is looking for and using so-called super corals – able to tolerate warmer water – that could be transplanted to parts of the GBR where other corals have been killed during bleaching events caused by rising sea temperatures.

One of the nation’s longest-running operators in habitat recovery is Greening Australia (GA). It’s been rebuilding and restoring destroyed or damaged Australian ecosystems for almost 40 years. How it does that takes many different forms, from large-scale tree and shrub plantings aimed at sequestering carbon and restoring degraded terrestrial, wetland or riparian habitats, to the regeneration of bushland disturbed by livestock grazing or fire.

GA is also highly active in supporting what’s becoming known as the “restoration economy”, a growing business and employment sector that covers everything from carbon farming, seed collection and supply, to bushland regeneration. For example, explains Dr Blair Parsons, GA’s Science and Planning manager in Western Australia, the organisation provides education and training for practitioners in natural landscape restoration and runs a national native seed business – Nindethana.

GA has had many success stories during the past four decades, including the restoration of large areas of riparian and wetland habitat in Victoria’s Gippsland Lakes. Another high-profile achievement, also in Victoria, is Haining Farm. This is a 59ha property in the Yarra Valley where GA is working with Zoos Victoria, Parks Victoria and the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, to restore habitat crucial to the survival of the critically endangered Leadbeater’s possum and the helmeted honeyeater.

GA’s largest program, Great Southern Landscapes, is attempting to redress over-clearing and resultant land degradation across an area of about 1 million square kilometres of agricultural land in southern Australia. “As a result of clearing in that area there have been long and protracted biodiversity declines and there’s no real sign of that letting up any time soon,” Blair says, agreeing that true ecological restoration is unlikely to be possible across much of that land. For the Great Southern Landscapes, GA is instead operating on a principle that about a third of the landscape needs to be under native vegetation for it to be able to retain some sort of natural balance. “We are really using that as the theoretical end point to drive where we want to go with that program,” Blair explains.

Last year, GA completed its largest single-season planting. From May to July, with financial support from petroleum exploration and production company Woodside, it planted 3 million trees and shrubs of 120 different native species

across 1500ha on a WA property called Cowcher. Strategically located adjacent to significant and biodiverse remnant vegetation, it had been badly degraded by farming that had begun there in the 1960s. Although no longer used for agricultural purposes, it would be near-impossible to return the land to its original state. But it’s being used to plant and connect habitat – as part of the ongoing Gondwana Link initiative – to support threatened species in the area. These include three birds – the malleefowl, Carnaby’s black-cockatoo and western whipbird, plus three mammal species – the red-tailed phascogale, western mouse and black-gloved wallaby.

A notable recent change to the way GA operates has been forced by climate change. “What we are needing to do now is work in climate-appropriate ways, so we can’t just put things back assuming it’s going to be fine because that’s what it looked like before,” Blair says. “We now need to consider how the conditions in an area are predicted to shift with a changing climate and what we have to do to accommodate that.”

Traditionally, GA would plant species based on local provenance, meaning it would use seeds and plants from areas as close as possible to the site being restored. “Now we are needing to take a ‘climate-adjusted approach’ to restoration, which is where you might find yourself collecting seeds from areas that are further along the gradient of where you perceive your climate will shift,” Blair says. “At the moment we are doing it in an experimental framework and working with researchers around the country who are leading this.”

Much of the new thinking is being led by CSIRO researchers, including Dr Suzanne Prober, who was one of the authors on the paper initiated by Dana. Suzanne, a vegetation ecologist with CSIRO Land and Water, believes that rather than struggling to achieve true ecological restoration for some beleaguered ecosystems, we need to instead be thinking increasingly about ecological “renovation”.

That means accepting that a habitat or ecosystem might never be able to be returned to its former state. “Instead, we should move forward with protecting and resurrecting what we can, but accept that it may not be identical to what was there before,” Suzanne explains.

It’s an approach many scientists are now talking about to salvage a future for the GBR.

“Renovation is about finding a balance to maintain what we value from the past to the maximum extent, but then accepting that to do that, we might have to do things differently,” Suzanne says. “For example, when rebuilding an ecosystem we may need to use genotypes or species that we expect will thrive under a future climate, rather than only those that were there in the past.”

A doyen of ecological restoration, Dr Tein McDonald, immediate past president of the Australian Association of Bush

Regenerators, says traditional restoration still has a huge role to play in rescuing Australia’s many beleaguered natural ecosystems. And she believes climate change can be accommodated in ways such as restoring bushland links between fragmented eco-systems. This will allow species to shift their ranges naturally as conditions change.

In fact, she believes ecological restoration is more important than it’s ever been. “Over the last 50 years, biodiversity has been crashing around the world and we are in for a major extinction event. Restoration is certainly part of the solution,” Tein says. “But it’s just a bandaid panacea if we think it’s going to solve the problem without us amending the causes in the first place.”

The Nature Conservancy (TNC), another major Australian non-government organisation operating extensively in this area, is trying all this and more to help revive the nation’s most damaged natural places.

Much of its work involves freshwater and estuarine ecosystems. But it does have a large presence in the top third of Australia where it’s working with Indigenous groups to restore the widespread use of traditional burning in tropical savannah ecosystems. “It’s not what people typically think of as restoration,” concedes Dr James Fitzsimons, TNC’s director of Conservation and Science. “But it is restoring an important ecological process that’s fundamental to northern Australian ecosystems.”

TNC is also very active in freshwater restoration, particularly in the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB). “The state and federal governments have large resources for buying water for environmental [purposes] there, but TNC wanted to test a different model for funding restoration,” James says. “So, we set up an impact investing fund called the Murray–Darling Basin Balanced Water Fund.”

Biodiversity has been crashing around the world and we are in for a major extinction event. Restoration is certainly part of the solution.”

The fund represents an opportunity for investors with a ‘green conscience’: water is still bought and sold in the scheme and is made available to farmers and irrigators when they need it most, which is where the fund generates profits, much of which are returned to investors. “But critically, some element of it, either water rights or hard cash, gets donated back to the environment for watering and restoring wetlands – often nationally important wetlands – particularly on private land, which otherwise wouldn’t get water out of government environmental watering programs,” James explains. “It’s an important way to diversify where environmental flows go, but, importantly, also tests a different income stream for restoration in the MDB rather than just relying on government funding or philanthropy.”

TNC’s other main restoration work involves shellfish reefs across southern and eastern Australian coastal waters. These are based mostly on oyster and mussel species and would have been common when Europeans arrived in Australia. Many of them were based on the Australian native flat oyster (Ostrea angasi). “It’s very similar to the European oyster and so the early settlers knew how to harvest it,” James says. “They were gathered for food but their shells were used as a source of lime for construction. All that shell biomass was taken out of the system and that was a critical problem – oysters require older oyster shells to settle and grow on. The ecosystem lost the ability to re-establish itself.”

There are different oyster reefs in different parts of Australia, but those based on Sydney rock and Australian flat oysters have been decimated in south-eastern Australia. TNC estimates that as little as 2 per cent of that ecosystem survives.

“It’s probably our most critically endangered marine ecosystem and I think most conservation scientists wouldn’t have known about it until recently because it was outside of living memory when most of it disappeared,” James says. “So there’s no reference point to what was there, and so to help guide their restoration work the team here in Australia has looked at historical records around fishing legislation and regulations from way back in the 1800s.”

They’ve also used old explorers’ records and journals for reference. “They often talk about coming into bays alive with oysters, a real shipping hazard,” James says. “So there’s a lot of back history to show that we had really extensive reefs throughout the system. There’s only one area of any substance left and that’s in Tasmania as a kind of reference point reef.”

TNC is working in estuarine waters off WA, Adelaide in South Australia, Noosa in Queensland and in Melbourne’s Port Phillip to restore this ecosystem, and recently received an additional $20 million of federal government post-COVID-19 economic stimulus funding to expand the work.

“These activities are quite creative and job intensive, which shows restoration is a really important activity in stimulating local economies, and getting people employed,” James says, adding that restoration can be expensive and sustainably financing the sector in the long term is going to be crucial. “One of the challenges I think we face is that degrading activities – like soil erosion and vegetation clearing and the resulting loss of species – aren’t adequately incorporated into the economy, and because of that it’s hard to incentivise the protection, management and restoration of natural places and natural resources going forward.

“So until we start factoring those in as critical parts of the economy, it’s going to be a harder task to shift the dial as far as we need to in terms of restoration in Australia, but it is starting to happen and the carbon market is certainly helping it.”

James knows many places TNC is working can’t be fully returned to their former glory, or achieve an idealised view of restoration. “Perhaps we need to start thinking of protected areas more as ‘safe places for nature’ as opposed to systems that are static and staying there forever,” he says. “We might have to change our thinking around what is natural – what is good quality and what is not – for many of these places going forward, because we know they’re going to shift in the face of climate change.”