“You easily feel helpless and overwhelmed”: What it’s like being a young person studying the Great Barrier Reef

IN 2016, ONE of Australia’s most respected coral biologists Terry Hughes tweeted a graph depicting the extreme coral bleaching event that occurred on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016.

Alongside the graph, Terry wrote, “I showed the results of aerial surveys of #bleaching on the #GreatBarrierReef to my students, and then we wept.”

The northern parts of the Great Barrier Reef were the hardest hit, with 81 per cent considered “severely bleached”. The central third of the Great Barrier Reef suffered even more bleaching in 2017. This was the first ever recorded back-to-back bleaching event caused by global heating from CO2 emissions.

I showed the results of aerial surveys of #bleaching on the #GreatBarrierReef to my students, And then we wept. pic.twitter.com/bry5cMmzdn

— Terry Hughes (@ProfTerryHughes) April 19, 2016

In the November/December issue of Australian Geographic (on sale 7 November 2019), Terry further detailed the challenges faced by young coral reef scientists.

“We have to relearn how the system is now working,” he says. “It is a huge research challenge for the next generation of marine scientists.

“Many of my students have had to redesign their projects because their corals died, but I tell them to hang in there because there has never been a greater need for coral reef researchers.”

Queensland is the unofficial home of marine science in Australia given its proximity to institutions such as the Australian Institute for Marine Science and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, and the Reef itself.

The ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, headquartered at James Cook University in Townsville, is particularly distinguished in the field of marine science. We sat down with three ARC students to ask them what it’s like studying the Great Barrier Reef in the midst of the climate crisis.

Andreas Dietzel

Andreas began his PhD on the Great Barrier Reef in 2015, and following the bleaching events of 2016-–2017, adapted the focus of his research to explore the consequences of the unprecedented event.

Alongside Terry Hughes, Andreas helped map the 2016 bleaching event in the northern Great Barrier Reef (the data was included on the map tweeted by Terry).

“My colleagues and I were just on our way back from two physically and mentally challenging weeks surveying the most severely bleached reefs in the far north, when we heard the news that Donald Trump had just been elected president of the USA,” Andreas says.

“A feeling of shock and disbelief mixed with the sobering realisation that the chances of averting further climate breakdown, whose impact on even the most remote parts of the Reef we had just witnessed, was quickly dwindling.

“When mass bleaching returned in 2017, the fear that climate change was already here now and not a distant, slowly unfolding threat, became stronger and has stayed with me ever since.”

While Andreas didn’t expect his PhD to be easy, it’s come with added stress.

“Feeling overwhelmed is a natural part of any PhD but witnessing and documenting an ecosystem as marvellous as the Great Barrier Reef degrade so significantly over the course of your own PhD comes with its own challenges,” Andreas says.

“The question I have often asked myself is how to make a difference as a PhD student or early-career scientist and significantly add to a body of knowledge that has too often fallen on deaf ears with politicians.

“Building the emotional resilience to not let your professional life impact your private life too much is particularly challenging when you are not only trying to be part of the solution but your Western lifestyle also makes you part of the problem.”

The biggest challenge for young marine scientists, Andreas foresees, is factoring in the possibility of disturbances affecting their research projects, such as loss of coral.

“Having a back-up plan and being able to adjust your goals and methods quickly will be essential.

“As disturbances become more frequent and larger, reefs and reef dynamics will resemble their historic counterparts less and less.

“On one of my first trips to the GBR, we surveyed a breathtaking reef. Back at the surface I shared my excitement with my colleagues, who were quick to note that most reefs used to look like this or better.

“The baseline of what a pristine reef should look like has and will continue to shift as reefs continue to degrade.”

Alexia Graba-Landry

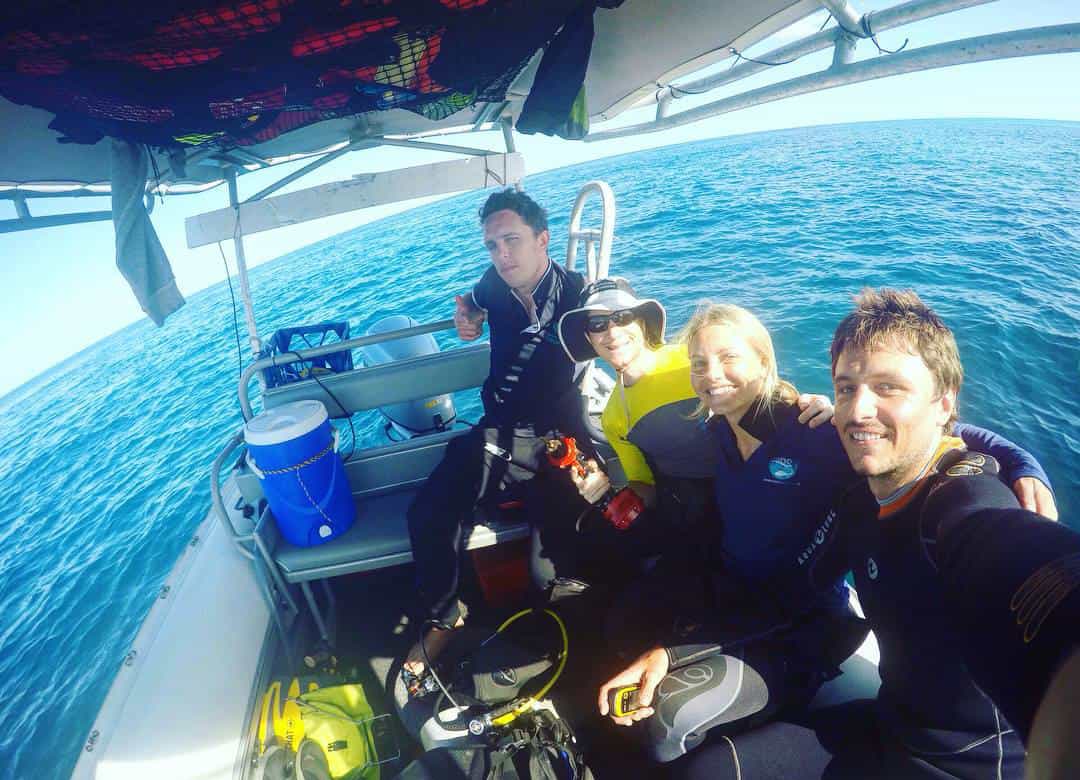

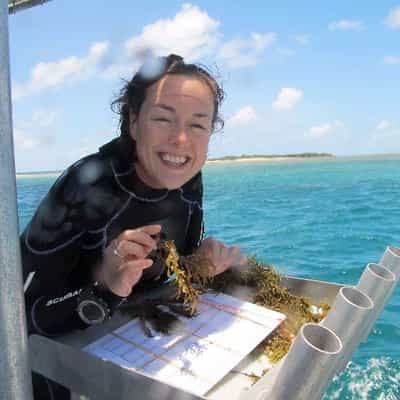

In total, Alexia has spent over 600 field-work days on the Great Barrier Reef for both her PhD research and related projects.

Alexia’s PhD investigates the influence of temperature on fish-algae interactions on coral reefs.

“This is important because by eating the algae, the fish keep the algae in a cropped state, and make space for corals to settle and grow,” Alexia explains.

“Understanding how this important process might change as oceans continue to heat up can give us an idea of what reefs might look like into the future.”

Alexia’s thorough knowledge of the Great Barrier Reef gave her the opportunity to work as a camera assistant and dive supervisor for the BBC’s Blue Planet 2 program.

But the long amount of time she’s spent on the Reef has opened her eyes to the immense pressure its under.

“Studying climate change and the Great Barrier Reef can sometimes be overwhelming, particularly when the results of your studies confirm just how vulnerable coral reefs are to climate change.

“Coral reefs are one of the most threatened ecosystems, and during my short time researching the reef, I have witnessed the devastating effects of recurrent cyclones, and recurrent coral bleaching events, and widespread coral mortality.”

Alexia was a part of surveys that quantified the coral loss of the northern parts of the Great Barrier Reef, where she’d already witnessed the impacts of cyclones Nathan and Ita years before.

“I think a big challenge for young people studying the Reef is that they will never get to see it as it was.

“I don’t think any of us will ever get to fully comprehend what a pristine reef looks like, or that it was right in our backyards.

“Our reefs will be different to the generations before us: lower in biodiversity and complexity.”

Madeline Davey

Madeline is currently undertaking a PhD in marine spatial planning at the University of Queensland that she hopes will inform robust conservation plans for the Great Barrier Reef, and coral reefs around the world.

For Madeline, the biggest challenges for young marine scientists is facing the reality that much of your research will be ignored, as well as reading media reports that misrepresent the current trajectory of the Great Barrier Reef.

The 2016–2017 bleaching event left Madeline feeling sad, but mostly defeated.

“With catastrophic events like this, it is incredibly hard to be optimistic about the future, but as a coral reef scientist, I think it’s a part of my role to motivate citizens to stay informed and engaged,” Madeline says

“It is really challenging to navigate the media reports and persistent questions about whether the reef is ‘really’ dead. It is incredibly hard to give decisive answers about an uncertain future when we don’t know ourselves, and so much depends on whether or not people take action.

“It’s also especially hard to keep studying and working in coral reef conservation when it often feels like all this hard work and research is ignored by those who have power to make the changes we need to see to ensure the Reef retains its wonder and global importance.”

Madeline says, however, that she personally witnessed how the back-to-back bleaching event got Australians more concerned about the science of climate change.

“I’ve been a CoralWatch ambassador since 2017, which gave me good insight into the number of concerned citizens who wanted to know more about what coral bleaching is, and what they can do to help prevent further devastation to our reef.”

The biggest challenge for young marine scientists, Madeline says, is centred on innovation, specifically the question, “how can we assist in rapid recovery of coral reef ecosystems?”