New website helps coastal councils adapt to rising seas

THE WILD STORMS that lashed eastern Australia earlier this year damaged property and eroded beaches, causing millions of dollars’ worth of damage. As sea levels rise, the impact of storms will threaten more and more homes, businesses and services along the coastline.

CSIRO projections suggest that seas may rise by as much 82cm by the end of the century. When added to high tides, and with the influence of winds and associated storms, this can mean inundation by waters as high as a couple of metres.

As a community, we have to start deciding what must be protected, and how and when; where we will let nature take its course; how and if we need to modify the way we live and work near the coast; and so on. Many of these decisions fall largely to local governments.

RELATED: King tides and wild winds create perfect storm

We have launched a website to help local councils and Australians prepare for a climate change future. CoastAdapt lets you find maps of your local area under future sea-level scenarios, read case studies, and make adaptation plans.

How will sea-level rise affect you?

Using sea-level rise modelling from John Church and his team at CSIRO, CoastAdapt provides sea-level projections for four greenhouse gas scenarios, for individual local government areas. This also provides a set of inundation maps for the selected local government area.

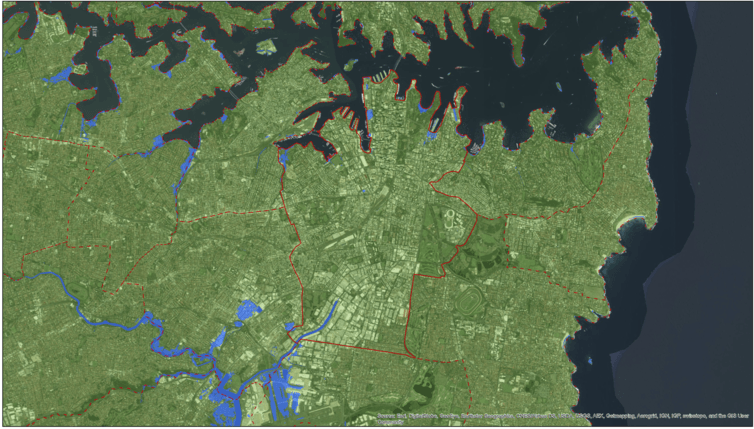

Sydney’s possible sea level in 2100 under a worst-case scenario. Inundated areas shown in pale blue. (Source: NCCARF)

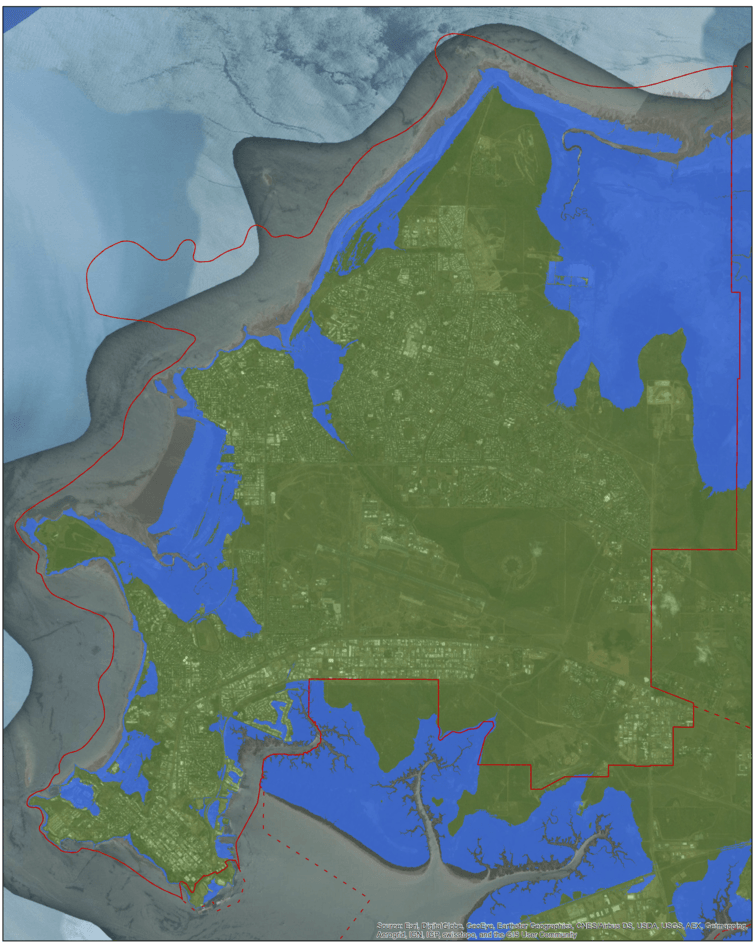

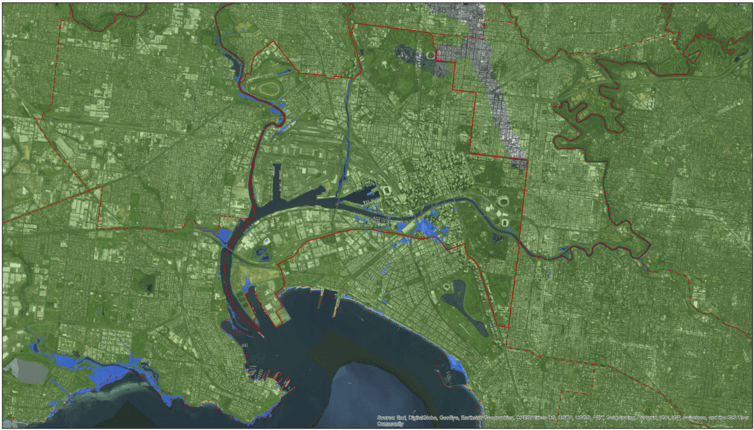

The inundation maps (developed by the Cooperative Research Centre for Spatial Information) show the average projected sea-level rise for a particular climate change scenario, combined with the highest tide. The method provides an approximation of where flooding may occur.

Because water is simply filled onto the map according to elevation, it doesn’t account for things like estuary shapes and water movement, the behaviour of waves and so on.

Brisbane’s possible sea level in 2100 under a worst-case scenario. Inundated areas shown in pale blue. (Source: NCCARF)

But both the maps and the sea-level projections are a useful way to start thinking about where risks may lie in any given local government area.

CoastAdapt also looks at what we know about coastal processes in the present day. Understanding these characteristics helps us understand where and why the coast is vulnerable to inundation and erosion.

For instance, sandy coasts are much more vulnerable to erosion than rocky coasts. The information will help decision-makers understand the behaviour of their coasts and their susceptibility to erosion under sea-level rise.

Darwin’s possible sea level in 2100 under a worst-case scenario. Inundated areas shown in pale blue. (Source: NCCARF)

Local councils already adapting

Adaptation is already happening on the ground around Australian local councils. We have highlighted several of these on CoastAdapt.

In the small seaside town of Port Fairy in southeast Victoria, for example, an active community group is monitoring the accelerated erosion of dunes on one of their beaches. The council and community have worked together to prioritise protecting dune areas with decommissioned landfill to prevent this rubbish tip being exposed to the beach.

Other councils have already undertaken the process of assessing their risks and drafting adaptation plans.

Low-lying areas in the City of Lake Macquarie already experience occasional flooding from high seas. This is expected to become more common and more severe.

Lake Macquarie Council has successfully worked with the local community to come up with 39 possible management actions, which the community then assessed against social, economic and environmental criteria. The area now has a strategy for dealing with current flooding and for gradually building protection for future sea-level rise.

This approach has engaged community members and given them the opportunity to help decide the future of their community.

Melbourne’s possible sea level in 2100 under a worst-case scenario. Inundated areas shown in pale blue. (Source: NCCARF)

Getting prepared

What stumps councils and other coastal decision-makers is the scale and complexity of the problem. Each decision-maker needs to have some sense of the risk of future climate change to their interests, then develop plans that will help them to cope or adapt to these risks. Planners and adaptors must navigate uncertainty in where, when and how much change they must consider, and how these changes interact with other issues that must be managed.

To better understand the risk, decision-makers need access to timely, authoritative advice presented in ways and levels that are useful for their needs. This is particularly true for an issue such as climate science, which is technically complex.

Climate projections, particularly at the local level, come with a level of certainty and probability. The further we look into the future, the more extraneous factors are unknown – for example, will global policy succeed in bringing down greenhouse emissions? Or will these keep increasing, which will necessitate planning for worst-case scenarios?

RELATED GALLERY: Powerful storm photography

Add to this the questions around legal risk, financing adaptation measures, accommodating community views and so on, and the task is daunting.

That’s the thinking behind CoastAdapt – the first national attempt to create a platform that brings together a range of data, tools and research that have been developing and growing over the last decade. As well as maps and case studies, we’ve also built an adaptation planning framework (Coastal Climate Adaptation Decision Support) and set up an online forum for people to ask questions, exchange ideas and even pose questions to our panel of experts.

The author would like to acknowledge the work of staff of the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility. CoastAdapt is in beta version and is seeking feedback. The final version will be released in early 2017.

![]()

Sarah Boulter is a Research Fellow at the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Griffith University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

READ MORE:

- Massive storms are polluting our oceans

- Pulling the plug on plastic