Why (most) Aussies love daylight saving

Two out of three Australians will “fall back” an hour as daylight saving ends for the season.

Like clockwork, countless opinion pieces will emerge in the media. Many will argue that daylight saving is pointless, outdated or even unhealthy, and we need to get rid of it. Others propose ditching the biannual time change for “permanent” daylight saving, which would extend winter evenings in exchange for darker winter mornings.

In sharp contrast to what many sensationalised reports and opinions might suggest, my research results indicate the vast majority of Australians – 80 per cent – support daylight saving.

A representative survey of more than 1,100 people found majority support, even in Queensland and Western Australia. Furthermore, this is true across occupations, states, income levels, household status, employment status and political affiliation.

That said, there were some differences between those who support daylight saving and those who do not.

So who typically supports daylight saving?

Supporters of daylight saving are on average six years younger that its opponents. Supporters of daylight saving are more likely to be female, higher-income, urban and employed full-time. Those against it are more often male, lower-middle-income, rural, retired or employed casually, and born in Australia.

Support for daylight saving is strongest among Australian Greens and Liberal Party voters.

Supporters of daylight saving also tend to live farther south, where the difference between summertime and wintertime daylight hours is greater.

Occupation was also important. Those who work outdoors – such as labourers, tradespeople and technicians – are often less supportive than their white-collar counterparts, who most often work indoors.

Why do we have daylight saving?

A Kiwi entomologist named George Hudson is widely credited with creating daylight saving. His motivation? So he could collect insects later into the evening.

The basic premise for daylight saving is that afternoon daylight is more useful than early morning daylight, so we “borrow” an hour. In the winter, we return the hour to the morning, so we can wake up closer to dawn.

Before the Industrial Revolution, time and time zones were not universally observed, as agrarian work could be adjusted to sunrise and sunset times.

Nowadays, clock time is essential to meet the demands of our busy schedules. We need standardised school hours, shop hours and working hours. The implication of this, though, is that a nine-to-five job gives someone in Brisbane, for example, three hours of daylight before work, but only an hour afterwards.

Could we just wake up earlier? Sure, but shops are closed in the mornings and most workers cannot simply knock off at 2pm to enjoy the rest of their afternoon. In fact, golf clubs are some of the biggest proponents of daylight saving.

So, although daylight saving may seem anachronistic, it appears to be the most palatable solution for adjusting to seasonal changes in day length.

Confusing time zones are a problem

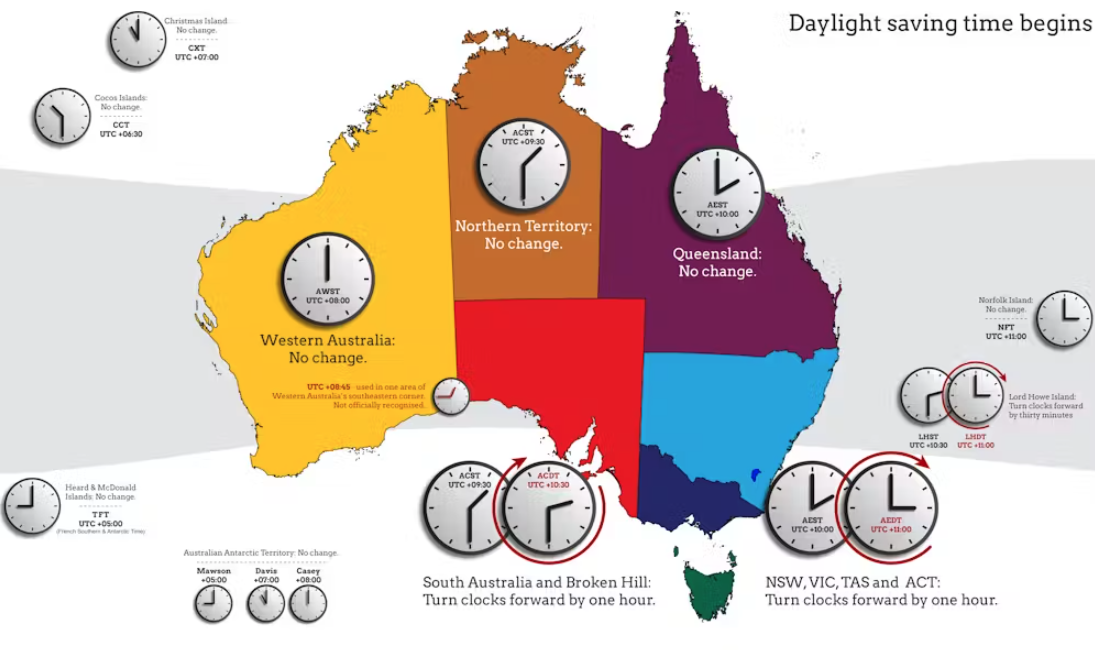

Part of the debate stems from the fact that Australia has a unique time-zone structure. Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania, South Australia and ACT have observed daylight saving since 1971, but it gets much more complicated than this.

In the winter, Australian states and territories observe three time zones. In the summer, this increases to five. When we include territorial dependencies such as Norfolk and Christmas Islands, Australia observes 10 time zones in the summertime, or 11 if you count Eucla’s local time zone.

To put this into perspective, all of China operates on a single time zone.

For many Australians, the status quo works, because it aligns “social noon” with solar noon. My survey results confirm the middle of respondents’ waking day – referred to as “social noon” – was 2.24pm on weekdays and 3.07pm on weekends. That’s more than three hours after solar noon (when the Sun is at its highest point in the sky) without daylight saving.

The following maps show current time zones in summer and winter, and the proposed alternatives discussed below. Use the slider to reveal the alternatives.

How could daylight saving be improved?

There have been various proposals to reconfigure Australia’s time zone regime.

“Permanent daylight saving” is an idea that would realign Australia’s current time zones so as to obviate the need for the biannual change. This would permanently shift Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne an hour or half-hour forward.

Many similar proposals have been floated in both the United States and Europe, most notably the US Sunshine Protection Act.

Another idea is to eliminate time zones entirely. As Johns Hopkins’ Steve Hanke and Dick Henry have proposed, the entire world would run on Greenwich Mean Time – or, more precisely, Co-ordinated Universal Time (UTC) – and hours would be locally adjusted. As it stands, there are 38 “UTC offsets” worldwide – a rough proxy for the number of time zones.

Queensland and Western Australia are perhaps the most significant battlegrounds in Australia’s daylight-saving debate. Both states cover vast areas, incorporating tropical and temperate regions. Brisbane, for instance, is closer to Melbourne in Victoria than to Cairns in Far North Queensland.

In both states, there’s a geographic divide, with the majority of daylight-saving supporters in and around the state capitals, Brisbane and Perth, in the south. Though both states have held referendums on the issue, it has been 15 years since Western Australians have had a say and 32 years since Queenslanders have.

If each state held another referendum today, survey responses suggest both would find widespread support. Politicians may need to think carefully, though, about how to address each state’s internal divisions.

Thomas Sigler, Associate Professor of Human Geography, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.