On the slopes of Sandbanks Tier, at the heart of the Central Plateau in lutruwita/Tasmania, boulder fields pour towards the shores of yingina/Great Lake like a river of rubble. For many, climbing this rarely visited mountain is an exercise in gymnastics, hopping and scrambling over rock, but Lewi Taylor moves easily, his long strides turning the puzzle of boulders into little more than stepping stones.

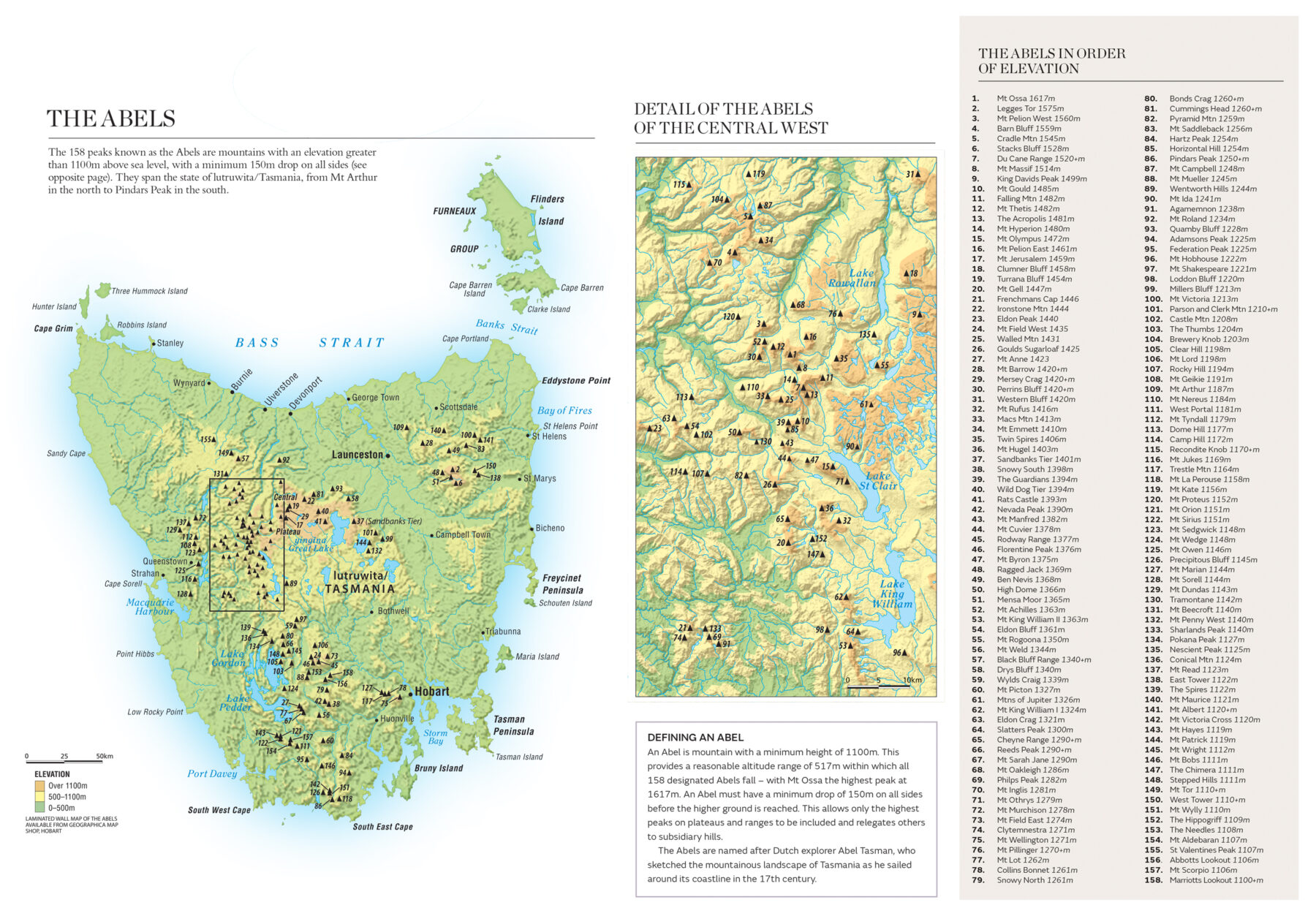

The last time Lewi was on this 1401m-high mountain, he could see little. It was dark and he was rushed. He’d started ascending this peak at 5am, and he planned to climb four more mountains that day. It would be the longest day in his quest to climb the Abels – the 158 Tasmanian mountains taller than 1100m above sea level, with a drop of at least 150m on all sides – in 158 days.

Named for Abel Tasman, the first European to sight Tasmania in 1642, the concept of the Abels was conceived in the early 1990s, and while they’re little known outside of their home state, their recognition has grown rapidly on the island. At the time of writing, just 31 people had completed the Abels, but more than one‑third of those “Abelists”, including Lewi, had done so in the last 18 months.

This day, as Lewi ascends Sandbanks Tier again, things are more leisurely. He’s here to finally take in the view, which comes as he rises onto the summit ridge, peering down onto yingina/Great Lake and as far as kunanyi / Mt Wellington, half the island away. It was on that mountain above nipaluna/Hobart that his fundraising 158 Challenge began in January 2022 and finished more than five months later, on his 30th birthday. As he talks, it’s clear that the most exhausting thing about this day’s climb on Sandbanks Tier is the memory.

“It was one of those days when fatigue and ambition came to a head,” he says. “I had to complete Sandbanks Tier before 7am in order to pick up a key from a landowner for access to another Abel, which resulted in me starting at 5am in complete darkness. Coming down when it was wet, dewy, dark and misty, I slipped down a 2m-high rock into [Richea] scoparia and bush and scraped my legs pretty intensely.

“People will say that Sandbanks Tier is one of the gentler walks up an Abel, but I turned it into the hardest. And I continued that day, trying to do five Abels, and by halfway through the third Abel I was crying – literally in tears.”

Lewi didn’t manage to summit five Abels that day – he was beaten after three – but he did go on to finish all 158 mountains in 158 days.

In completing the climbs, he smashed the record for the fastest round of the Abels by more than two years and elevated the profile of this greatest of Tasmanian mountain missions.

Bill Wilkinson hasn’t completed the Abels – he remains about 20 peaks short and resigned to defeat by bad knees – but the concept wouldn’t exist without him. While visiting Scotland more than 40 years ago, the Launceston-raised bushwalker teamed up with a traveller from London to climb several Scottish peaks in the group known as the Munros.

Initially compiled by Sir Hugh Munro in 1891, the Munros are the 282 Scottish mountains higher than 3000ft (914.4m). Among Scottish walkers, climbing the Munros, aka “Munro bagging”, is a challenge that borders on a national obsession.

It was an experience that set Bill thinking. Could a similar model be applied to Tasmania’s mountains? On his return to Tasmania, he set off, not to the mountains, but to libraries, where he spent months poring over topographic maps.

“I played around with the mathematical modelling for a long time,” Bill says. “I had a model where I started at 950m minimum – I quickly got rid of that and then nearly stopped at 1050m. But then there were too many scrubby ones, so it ended up at 1100m. But then you’ve got plateaus and trying to work out whether they’re just one massive mountain, so that’s where the 150m (drop) came from. But I played around with a lot of different ideas.”

In 1994, Bill, working with six writers, published the first volume of The Abels: A Comprehensive Guide to Tasmania’s Mountains Over 1100m High, bringing the mountains to walkers’ attention and creating a quest that slowly gained traction – it would be 17 years before the first person, Phil Dawson, climbed every Abel.

Initially, the list contained only 155 mountains, because, despite the exactitude of his study, Bill missed three Abels: Tramontane, Sharlands Peak and Nescient Peak.

“I kept looking at the wrong contour for Nescient Peak,” he says. “That became locally known as Bill’s Abel. Nescient means ignorant – I was ignorant.” The trio was added to subsequent volumes of the Abels book, the most recent of which, Volume 1, 3rd edition, was published at the start of 2023.

In studying the maps, Bill noticed that nine of the peaks that qualified as Abels were unnamed. In his mind, he created names for them, finally applying to the nomenclature board of the day to have the titles adopted. Once he proved the mountains had no recorded Indigenous names, or hadn’t been christened by early explorers or settlers, his names – among them, Mensa Moor, Agamemnon, The Hippogriff and Mt Othrys – were accepted.

“It was great fun,” he recalls. “I tried to fit in with the local traditions. Mt Othrys I named because it’s next to Mt Olympus – the gods were on Mt Olympus and the Titans were on Mt Othrys, and they were fighting. And Agamemnon was Clytemnestra’s husband.” (Agamemnon and Clytemnestra mountains stand almost together beside Frenchmans Cap.)

Bill says the Abels aren’t a perfect model – the drop on Mersey Crag makes its status as an Abel disputable, for instance – but after nearly 30 years, they’re only growing in popularity, and he remains proud of the collection.

“The Abels are becoming part of the language of Tasmania,” he says. “I sometimes wonder whether the minimum drop of 150m could be a bit less, but when you start looking at their distribution, the state’s covered very, very well. And it’s a nice lot of mountains – there’s quartzite, dolerite, sandstone, conglomerate – and you’re walking in all sorts of different terrain – dry sclerophyll, wet sclerophyll, rainforest, buttongrass.

“Everything was very fluid early on, but once I established the model, I was very happy.”

By the end of 2022, 7390 people had completed the Munros. At the same time, just 25 people had climbed all the Abels. But only one person had done both.

Growing up in Scotland, Malcolm Waterston was once challenged by a teacher to climb all the Munros before he turned 21, but by the time he emigrated to Australia at the age of 31, he still had about 100 to climb.

When he spotted the Abels book by Bill Wilkinson et al. in a shop window in his adopted home of Queenstown, on Tasmania’s west coast, in the 1990s, it was like a love letter from home.

“As soon as I heard of the Abels, it became a challenge, because it made it so much like the Scottish scene,” Malcolm says, as we reach the summit of Quamby Bluff, the 1228m-high Abel in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. It’s a mountain Malcolm often returns to from his home in nearby Launceston, having climbed it about a dozen times.

After setting out to pursue the Abels peaks in the mid‑1990s, Malcolm retired from his vet practice 10 years ago, at the age of 60. It was partly to concentrate on his Abels quest, becoming just the sixth Abelist when he summitted on Camp Hill in January 2016.

All the while, the Munros called from across the globe, as did family tradition. Malcolm’s sister had completed two rounds of the Munros, while his father held the record for the longest time to complete the Munros, climbing his first peak before the age of 10 and his final one in his 80s.

On visits home, Malcolm slowly picked off unclimbed Munros until, by 2022, only 11 remained on his list. It was time to complete his mission, which he did (while infected with COVID) by summitting the 980m-high Beinn a’ Chochuill in September 2022.

As we look out from Quamby Bluff, Malcolm points out an amphitheatre of Abels – more than 16 peaks – visible from this grandstand and I ask him which of the challenges was tougher.

“The Abels are a far more difficult challenge,” he says. “There’ll never be as many people do them. My friends in Scotland who have climbed the Abels say that you throw away the Scottish mountain rulebook when you come to Tasmania. You play by completely different rules because of the remoteness, the terrain, the vegetation and the big rivers that you’ve got to cross at times. The Abels took me places I’d never have gone otherwise. It’s been a real journey and hobby. I’ve loved it as a lifelong thing to do.”

Becca Lunnon describes herself as the accidental Abelist, even the accidental bushwalker. When she moved to Tasmania in 2012, she was no bushwalker, but when she smiled her way into a job in a Hobart outdoor‑gear store, things took a turn.

“I’d been overseas and Mum had retired down here from Melbourne,” she says. “Within the first week of deciding that I was coming to Tasmania to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, I walked into a bushwalking store and was offered a job because of my smile. A couple of months after starting, I thought I really needed to actually use some of the gear so I could talk about it from firsthand experience.

“I was invited on a pretty spectacular trip to Scotts Peak on Lake Pedder, and we had a magical day. I was thoroughly addicted from that point onwards, and now here I am – bushwalking is one of the biggest parts of my life and my identity.”

.

In January 2023, Becca became the 26th Abelist when she summitted on Tramontane, a remote peak west of Lake St Clair. But what sets her apart from most Abelists is that she never set out to become one. There are several distinct mountain challenges across the state of Tasmania, from the Tasmania Connoisseurs Peaks Challenge (featuring the 125 favourite mountains of the challenge’s three creators, including Paul Geeves – the second Abelist) to the Abels, but the quest that captivated Becca from the beginning was the Hobart Walking Club’s Peak Baggers List, a spreadsheet of the state’s 481 mountains, with each peak assigned a point value out of 10, according to its difficulty.

Her attempt to climb every mountain in Tasmania began on the Abels because of the wealth of available information on them. Trestle Mountain, one of four Abels on the Wellington Range behind Hobart, was one of her earliest climbs, and the peak to which I was now hiking with her. She’d insisted we take it slow, because she was running in a 67km ultra event three days later, but still it was an effort to match her pace.

“I got very addicted very quickly,” she says, laughing as she recalls her first climb on Trestle Mountain 11 years before. “I decided I was going to ride my bike to Big Bend (an ascent of 1100m from Hobart) and then climb as many of the mountains as I could. I wanted to be up here for sunrise, so I set out at some ungodly hour, like 3am, slowly ground my way up the icy road, and then started walking. I found my way up Mt Connection, Collins Bonnet and Trestle Mountain, walked all the way back and rode home. I was very tired by the time I got there.”

It wasn’t until Becca had less than a dozen Abels to complete that she truly turned her mind to that particular quest, and it was only when she came to her final mountain that the realisation of what she was about to achieve was driven home.

“When I did my second‑last one, I wasn’t feeling like it was too much of an achievement, but then a friend said that

more people had orbited the moon than had climbed all the Abels,” she says. “When he said that, it made me think it was kind of cool.”

With the Abels complete, Becca’s mission to finish the Peak Baggers List continues. At the time we climbed Trestle Mountain, she had 32 more mountains to climb, mostly scrubby, off‑track peaks that she predicts will take her another two to three years to complete. Success would place her in an even more exclusive club, with only four people having climbed every mountain on the list. She will almost certainly become the first woman to do so, but, like so many Abelists, she notes that the joy of the climbs is less in the numbers than in the experiences, places and discoveries – external and internal – to which they led.

“It’s not really a competitive thing, it’s a sense of achievement that’s measurable,” she says. “It’s about the sunrises and sunsets, the birds, the encounters with whatever wildlife, just all those little things, as well as the actual climbing of the mountain.

“It’s given me a sense of knowing myself and has been key to learning about and developing my own self‑identity, self-confidence and self‑esteem – to move from somebody I don’t think I really liked, to somebody I do.”

Lewi Taylor blames his 158 Challenge on a single throwaway sentence after reading about Zane Robnik, the 26‑year‑old who completed the then‑fastest round of the Abels – two years and 197 days – in 2018.

“I said to a mate, ‘Just conceptually, what if you do one mountain a day?’” says Lewi. “He just looked at me, and the look said, ‘Well, you’ve got to try it.’ We checked it out, and over the course of 18 months really got our teeth into an itinerary. I’ve got quite a logistics brain, so the idea of connecting lots of mountains in a sequence that can give you a unique experience was what really appealed about the Abels.”

Along the way, after Lewi’s mum was diagnosed with breast cancer for a second time, it turned into a fundraiser, eventually raising $167,000 for Cancer Council Tasmania. For 158 days, Lewi’s life was reduced to the exhausting pursuit of peaks. “I’ll always say that the experience of hiking the Abels is more mental than physical,” he says. “If you do something every day for two or three months, you will become good at it. I essentially became a mountain goat in my body. I could no longer run, I could no longer jump, but I could climb mountains very, very well.”

Briefly, it looked like Lewi would complete the challenge one week early, but then, a fortnight out from the finish, his troubles began. The tail shaft fell off his car, and he then contracted COVID, forcing him to isolate on Tasmania’s east coast, sitting out a week of perfect weather and returning to the mountains just as heavy snow started to cover them. “I was waist‑deep in snow on those mountains for a few days,” he says.

It was just as his car died that, by chance, Lewi met John Carswell, the seventh person to complete the Abels. John gave him a place to stay in Launceston, the loan of his ute to keep the challenge alive, and then joined him on the final three peaks.

This day, on Sandbanks Tier, John has joined Lewi again, an odd couple of Abelists reunited on an Abel – Lewi, the fastest to have completed the mountains; and John, the slowest, climbing his first peak when he was nine and completing them 54 years later. Recalling his first climb, on Mt Owen, above his childhood home in Queenstown, John jokes that his Abels pursuit began with a tantrum.

“My older brother was 11, and my dad offered to take him to climb Mt Owen,” he says. “I wasn’t invited initially, and I put on a turn. I remember the effort I had to put in – turning on the tears, yelling and screaming, to the point where my mother went to my dad and said, ‘Trevor, I think you’d better take him with you.’”

More west‑coast Abels followed when John was a boy scout, though an attempt on Mt Geikie was defeated by heavy rain – five decades later, this 1191m-high mountain would be his final Abel. With him that day in 2016 was Malcolm Waterston, with whom he’d climbed so many of the Abels, and six years later he was part of the group that accompanied Lewi to his concluding summit of kunanyi / Mt Wellington in snow.

As I walked and talked with Abelists, this repeated crossover and interaction became a familiar pattern. Stories and climbs intertwined, until the Abels began to feel as much a community as a quest. Lewi says it was this, and the generosity of people like John, 40 years his senior, that finally got him over the line on time in his 158 Challenge.

“Something like this spans intergenerationally,” he says. “The act of bushwalking, of just being out in nature, is not specific to any one type of person. People just throw their arms around you.”

Like all great adventures, completion of the Abels leaves hanging the question of what next. Becca still has mountains to climb, Malcolm had the Munros to finish, and John has climbed five of the Seven Summits, the highest peaks on each continent. Lewi, too, has his sights ahead, but what he sees are more Abels.

“People said that Zane’s time was unbeatable, and people now tell me that no-one will ever do it quicker [than 158 days],” he says. “In my 158 days, I had 109 days of actual hiking, so I think it can definitely be done faster. Maybe I’ll do them quicker again myself to show that I’m not just full of arse. But that might be some time away.”