It was 3am and raining steadily as I laced up my battered hiking boots on a morning last May in Lamington National Park, a vast south-east Queensland wilderness about 110km by road south of Brisbane. I was at O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat – formerly O’Reilly’s Guest House – preparing to connect with a visceral piece of Australian history that began just after 1pm on 19 February 1937. That was when an Airlines of Australia Stinson Model A airliner carrying two pilots and five passengers left Brisbane’s Archerfield aerodrome bound for Sydney. It never arrived at its destination.

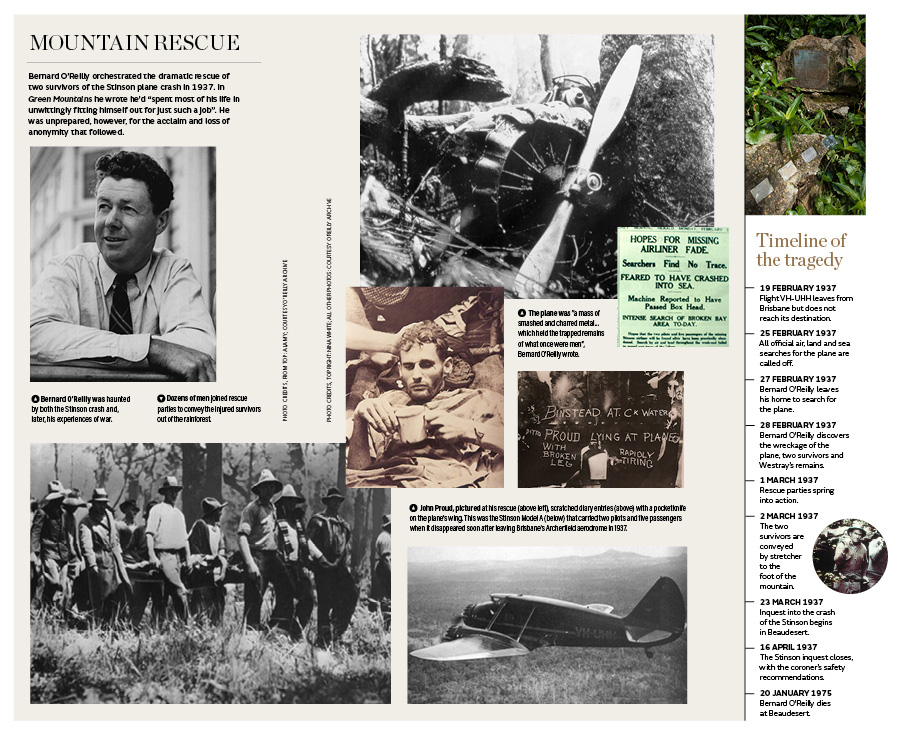

After extensive air, land and sea searches failed to find any trace of the plane, most people concluded it had crashed into the ocean. But Bernard O’Reilly, of the eponymous family that opened the famed guesthouse, thought differently. There was, he recalls in his 1940 book Green Mountains, a ferocious cyclone on the day the Stinson went missing and he’d spoken to several people, including his brother, who’d seen it flying towards the cloud-shrouded McPherson Range. “The answer was lying somewhere…amid eighty thousand acres of unbroken, trackless jungle,” he wrote.

Using a topographic map, pencil and foot rule, Bernard, then aged 33, drew a line from the plane’s last sighting, along the expected line of flight to Lismore, which crossed four high mountain ranges. He figured the missing plane had to be on the northern slopes of one of them, and he was going to find it.

Rhelma Kenny, Bernard’s only daughter, remembered begging to accompany her father as he pulled on his boots on the morning of 27 February 1937. “My mother came out and was worried because, obviously, if he broke his leg out there, he was going to stay there, and nobody was going to find him,” Rhelma recalled before her recent death.

Bernard had been exploring Lamington NP, gazetted in 1915, since he was a boy. The family’s guesthouse was visited by scientists and his job was to boil the billy for them. “He was hungry for knowledge and just soaked it all up,” Rhelma said. Bernard was in his element in Lamington, the last place on earth where ancient Antarctic beech trees and towering hoop pines stand side by side, and the only place where creatures such as Albert’s lyrebird and the electric blue Lamington spiny crayfish are found. But the rainforest is as unforgiving as it is beautiful. Everything seems to have fangs, claws, barbs, pincers, stingers or poison.

Bernard knew the dangers. Before launching his search for the airliner, he packed Condy’s crystals (potassium permanganate – a popular snakebite treatment of the day), a safety razor and a length of cord to serve as a ligature. He left the guesthouse on horseback before continuing on foot. During the next few harried days he found the crashed plane and orchestrated the rescue of its two survivors, becoming a national hero. It was a long and arduous journey that changed his life.

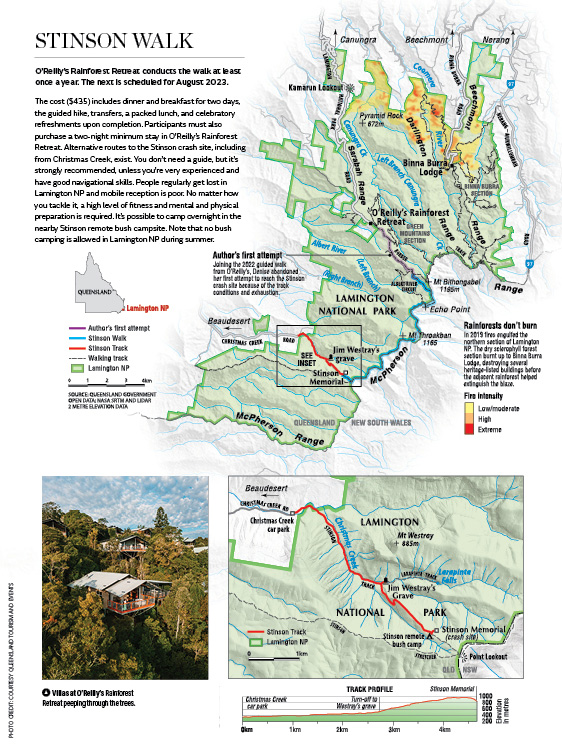

Bernard’s remarkable journey is commemorated by a gruelling guided hike, which is how I came to be lacing up my own boots that wet morning last May. The Stinson Walk retraces Bernard’s footsteps across the 37km one-way route in a single day. It’s organised by O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat and leaves from there, within sight of a replica plane built for the 1987 film The Riddle of the Stinson, which starred iconic Aussie actor Jack Thompson as Bernard.

Although the original trek had taken place in February, the annual Stinson Walk has been shifted to May, traditionally a drier month. “It’s quite slippery and muddy at the best of times,” says Shane O’Reilly, managing director at the retreat and great-nephew of Bernard.

Wil Buch, ranger-in-charge of Lamington NP, says the downpour that flooded Australia’s east coast during the first half of 2022 dumped about 2000mm in four months on the park. It had cancelled the previous week’s Stinson Walk, saturated the ground, and turned every training hike into damp, muddy torture. During a 16km round trip to Echo Point the previous weekend, for example, the walking track had been indistinguishable from a waterfall and the leeches relentless. So, as the rain continued, it was with a mix of anticipation and dread that I joined 10 other people, plus two guides, to set off at 4am in the pitch black. It was imperative to maintain a good pace throughout, our guide Nathan Wilshaw advised at a briefing the night before.

“We need to be at the bottom of the hill by dusk; it gets dark very quickly,” he said. We proceeded down the Border Track, our headtorches illuminating the raindrops in front of us like a trillion fireflies. Despite having trained for months, I was quickly outpaced. I soon gave up skirting the track’s edges to dodge the muddy puddles, and instead stomped through the middle of them, while the fitter hikers weaved around and past me.

Even before we reached the Albert River Circuit turnoff, I’d fallen so far behind that the lights from the rest of the group were no longer visible to me. I was soaked and the incessant squelch of my boots told me they were filled with mud. I struggled a little longer, trying to reconcile two warring voices in my head. “I can’t do this for 12 more hours,” said one. “Candy-ass,” said the other. Ultimately, I was one of four hikers who turned back before the “point of no return”, where it becomes riskier to return than continue. Demoralised, I walked back to the retreat in the dark. Even my headtorch seemed to dim. Under the impenetrable canopy of trees the darkness closed in completely.

The remaining walkers, including photographer Nina White, forged on to the remote Echo Point lookout, where, given the white-out conditions, there was no sunrise view. They then followed Nathan off-track, to traverse the same series of peaks and gorges O’Reilly tackled 85 years earlier through the barely changed jungle.

“Visibility is limited to ten yards by a tangle of tough green vine, as dense as wire netting, and covered with murderous thorns,” Bernard wrote.

Six hours hiking from Echo Point landed the 2022 group at Mt Throakban (1156m), where Bernard, on the second day of his search, had spotted a burnt tree canopy in the distance. It had confirmed his hunch about the missing plane. “No natural fire had occurred in that dripping rain forest since the world began. But a hundred gallons of petrol…” he wrote.

By lunchtime, our group reached Point Lookout, not far from the site where O’Reilly found “a mass of smashed and charred metal”, along with two plane crash survivors – John Proud, whose broken leg was infested with maggots, and Joseph Binstead.

Poor conditions and patchy reception prevented further updates from our group’s remaining hikers until their return the night after they set out, so I headed to the timber-panelled library at the retreat to pick up the story’s threads. Here, alongside a propeller, a smashed windscreen, and various other bits of metal from the plane, a photo of John Proud taken soon after rescuers reached him is displayed. “I don’t think that man survived, he looks dead already,” a small boy next to me said to his mother.

Bernard knew the men’s survival depended solely on how quickly he could bring help. He’d learnt that a third survivor, Englishman James Westray, had left to raise the alarm the morning after the plane had crashed, but he hadn’t returned.

Bernard followed Westray’s tracks to a waterfall, where a clutch of mangled stream lilies revealed the man had fallen several metres to the base. From there he’d struggled on for miles, crawling. Eventually Bernard spotted him, propped up against a boulder, bathing a bare, broken ankle in the creek, a burnt-out cigarette butt between his fingers.

But as Bernard drew closer, it became clear that James Westray was dead. “Time will never remove that picture of him, sitting with his back to the rock,” he wrote.

The disturbing sight propelled Bernard’s final, frantic dash to civilisation along what he hoped was Christmas Creek. From there a rescue party was assembled and, along with them, Bernard re-entered the jungle by lamplight.

They carried the dead man to the grove of palms beside Christmas Creek where he still lies buried, before continuing on to reach the two survivors. Today, the rough river stones that mark Westray’s grave are blanketed in moss and the inscription on his headstone has deteriorated, but the site has lost none of its solemn, ethereal beauty. I visited three weeks after my failed attempt to complete the Stinson Walk, having enlisted Nathan to guide Nina and me to the crash site via an alternative route from the end of Christmas Creek Road.

The first part of the 9.5km round trip follows the creek along which Bernard led a doctor, and men carrying food and medical supplies, to the survivors. Meanwhile, a larger rescue party cut a longer but flatter track along the Lamington Plateau ridgetop so they could carry the men out by stretcher.

We sat on a fallen log in the dappled shade, listening to the sound of the still-swollen creek nearby and reflecting on how close Westray came to being the hero of this story. When he died – of internal injuries and exposure, according to a post mortem – he was only a few miles from the nearest farmhouse.Nathan says his parents flew out, intending to exhume their son’s body for an English burial, but when they saw his peaceful resting place, they changed their minds. “It’s not a bad place to spend eternity,” Nathan adds.

The first stretch of the steep, uphill climb to the crash site begins close to Westray’s grave. Clutching at tree roots and trunks, we scrambled on all fours up a near-vertical slope. At one point, spread-eagled on the side of the mountain, I lost my footing, and slid several metres down, trying hopelessly to grip the loose soil.

After the first few hundred metres the track levelled out a little, allowing us to better appreciate glimpses of orchids, fern grottoes, towering brush box trees with their gargoyle trunks, and the sprawling, intricate roots of strangler figs.

Massive landslides and tree falls have, Nathan says, reshaped this route and shifted what is left of the Stinson wreckage by about 50m. We’d hiked for hours, scaled a sheer rock face using ropes, and passed through the Stinson remote bush camp, before reaching the narrow final track to the isolated crash site.

Over time, souvenir hunters have removed most of the wreckage. All that remains is a large, cumbersome, rusted piece of metal, amid a tangle of native violets. There’s also a collection of boulders bearing simple plaques dedicated to the pilot, co-pilot, and two passengers who died and were buried here.

O’Reilly was traumatised by what he found. He wrote the first section of Green Mountains to exorcise the horror, and to discourage further casual enquiries from a curious public. Yet even his description of the “sort of coldness that was worse than fear and worse than pain or shock” still downplays the impact on him of the events around finding the crash. That’s best gleaned from the inquest, which took place barely a month after the crash. From his hospital bed in Brisbane, Joseph Binstead testified about the moment Bernard found them: “He [Bernard] looked at my legs and said, ‘I thought I was scratched but it’s nothing.’ He then seemed to break up. He couldn’t talk”.

It wasn’t until I visited the crash site that I grasped the enormity of Bernard’s feat. On this cool autumn day, I stood in the clearing, closed my eyes, and imagined what it must have been like for the two injured survivors. I could almost hear the scratch of Proud’s pocketknife carving diary entries into the shattered wing and Binstead’s laboured breathing as he crawled over rocks to the water that kept them alive. Then I crouched to read the wording on the side-by-side plaques that mark their graves. And, as my index finger traced the weathered lettering, I shivered.

Survival struggle

Lamington NP is part of the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia World Heritage Area, listed in 1986 for “outstanding geological features displayed around shield volcanic craters and the high number of rare and threatened rainforest species”.

Lamington’s wild, primeval beauty attracts about 600,000 visitors a year, many of whom come to explore its more than 320km of walking tracks. The park is so vast that new species are still being discovered. In 2021 CSIRO scientists identified two new soldier flies endemic to the park.

Yet this fragile ecosystem is struggling for survival. In 2019 bushfires tore through 1574ha of Lamington NP, representing about 7 per cent of the total estate, reported Queensland’s Department of Environment and Science. The flames forced a one-night evacuation of O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat, and razed several heritage-listed buildings at the nearby historic Binna Burra Lodge.

Dr Melinda Laidlaw, a senior ecologist with the Queensland Herbarium, was attending a meeting at Binna Burra when the fires broke out.

“None of us felt particularly at risk at the time, because we had not seen these rainforests burn before, but in the coming days things got quite serious,” she says.

Since 2006 Melinda and her colleagues have been investigating the potential impacts of climate change on subtropical rainforest by observing changes in vegetation in 20 survey plots located within Lamington NP, ranging in elevation from 300m to 1100m. When it was safe to check on them, she found three of the four low-elevation plots were still smouldering. Melinda’s research also examines the impact of climate change on cloud forests – the wet, high-elevation rainforests that are typically shrouded in cloud, mist or fog.

Plants here derive 40 per cent of their annual water needs from cloud and fog, rather than from rain.

But as climate change forces that cloud cap to rise, moisture stress and bushfire risk increases. “Our modelling suggests that the cloud cap could rise up to a metre a year from where it sits currently,” Melinda says.

Human impact

The pandemic-related search for fresh air, open spaces and solace in nature has led to a rise in people visiting national parks. Mirroring a global trend, visitation to all parks in south-eastern Queensland increased during and after COVID, says Wil Buch, Lamington NP’s ranger-in-charge. Visitors to Daisy Hill Conservation Park, in south-east Brisbane, have risen by 50 per cent, and to Lamington, where Wil has been working for about a decade, have gone up by 25–50 per cent. “Some people have a bit more time on their hands,” he says. “Others, following COVID, are reassessing their lives and reconnecting with nature. Our biggest challenge at the moment, apart from severe weather events, is managing and directing that visitation and trying to minimise the impact.”

Lamington NP’s 21,000ha range from well-trodden paths at Binna Burra and Green Mountains, to remote, untracked wilderness. In February 2022 Wil’s team installed a track counter on the route from Christmas Creek to the Stinson crash site and Larapinta Falls and, months later, were surprised to read the results. “In four months, in the wettest year in a decade, we’ve had well over 900 people walking in,” Wil says. “That’s a huge number of people for a remote area of the park, where you need to be self-reliant and well prepared, and where there are no formed trails.”

The trail is becoming well defined due to the number of people using it in wet weather. “We try to keep southern Lamington free of formed trails, so you navigate there under the canopy using compass, map and GPS,” Wil says. “We try not to have the trails heavily marked, but they get wider in wet weather as people try to avoid the muddy sections by going around them. As the profile of the track widens, vegetation gets trampled on the edges, and in many of the cases, that vegetation is quite significant or rare.” Lamington has 68 plant species considered rare or threatened, including the macadamia nut, ravine orchid and red lilly pilly.

Poor visitor behaviour is also contributing to degradation of this pristine environment. In July, rangers were forced to undertake remediation works to hide inappropriate words and numbers carved into trees around the site of Westray’s grave in May. One tree was a white booyong estimated to be 500 years old. A man had earlier been fined $551 after admitting to the environmental vandalism.

Other as yet unidentified individuals have used machetes to hack down hundreds of walking stick palms, some hundreds of years old. “They’re maybe misguided, thinking they’re marking or improving the trail,” Wil suggests.

Many visitors are also failing to book and pay for camping permits before turning up at camping grounds.

Denise Cullen was a guest of O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat.