The big, bold and beautiful Brindabella Range – known affectionately and simply as “the Brindabellas” – forms the western boundary between the Australian Capital Territory and New South Wales. Just beyond it, in NSW, lies the picturesque Brindabella Valley. I’ve roamed this area’s moist eucalypt forests, lush creekbeds and rugged escarpments for more than three decades, revelling in its beautiful imagery, which is often so vividly recalled in the writings of famed author Miles Franklin.

Miles spent part of her childhood at Brindabella, and the area’s imposing landscapes and distinctively Australian wildlife feature extensively in her fiction, particularly in the novel All That Swagger.

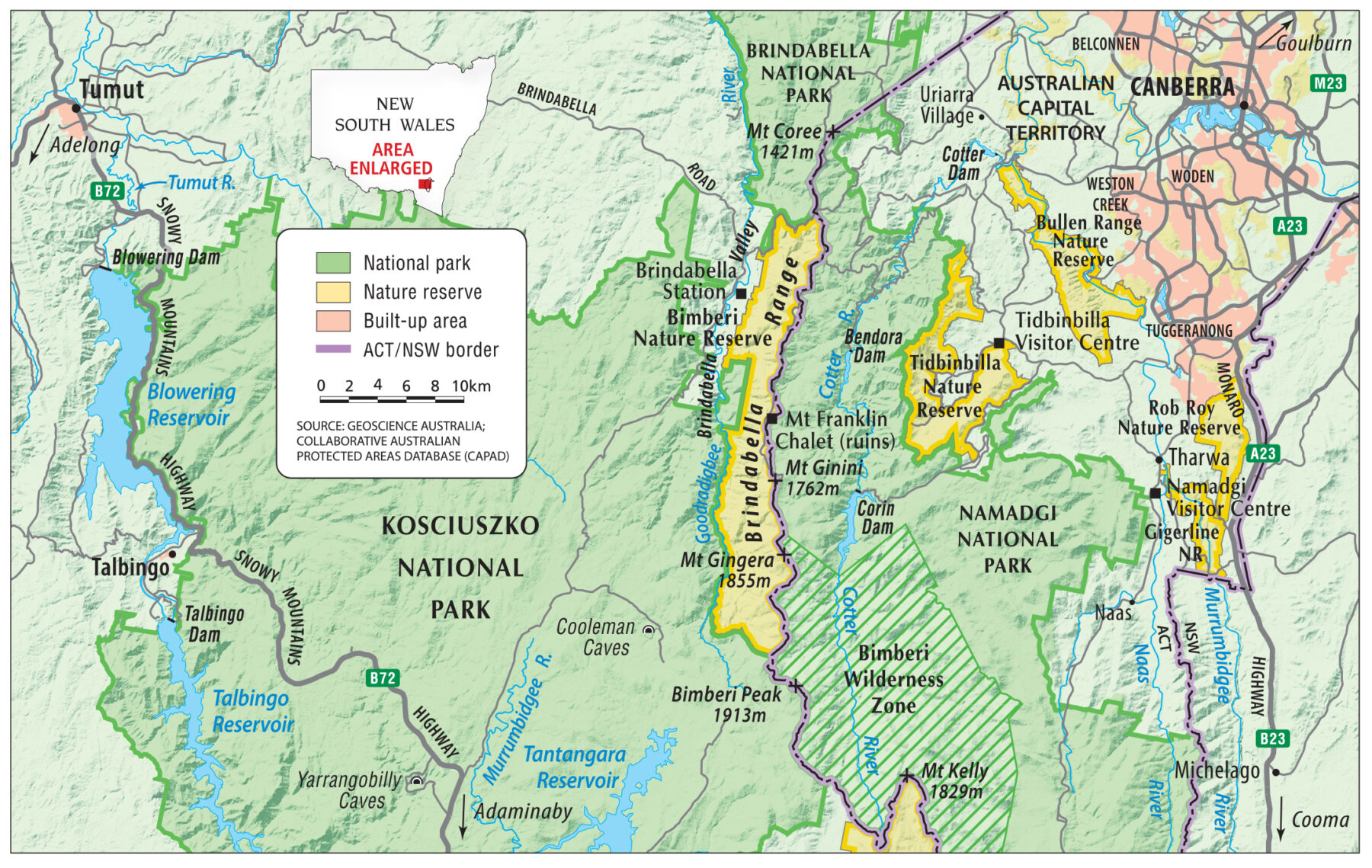

The Brindabella Range is a major feature of the Australian Alps National Parks and Reserves. On its ACT side, to the east, is Namadgi National Park; north, in NSW, is Brindabella National Park, while to the west are Bimberi Nature Reserve and Kosciuszko National Park. At 1913m, Bimberi Peak is the highest point, although the most distinctive mountain visible from Canberra is Mt Gingera, whose flat-top summit ridge rises to 1855m and holds snow for long periods in winter. Further north is 1421m Mt Coree – hump-shaped from one angle, pyramidal from another. Its cliffs of volcanic rock were known among earlier generations of rockclimbers. The granite you clamber over on peaks such as Gingera and elsewhere in Namadgi is more than 400 million years old.

Topped by snow-gum forests that have been stunted by exposure, the range has taller timbers lower down. Alpine ash stand majestically in cooler moist areas, and there’s also mountain gum and many others, plus wildflowers that are dazzling in summer. Sphagnum moss flats at Mt Ginini and Snowy Flats play a significant hydrological role in maintaining a steady water flow.

The Australian Alps are a place of moisture in a dry land. On the eastern (ACT) side of the Brindabella Range, streams tumble into the Cotter River, which flows north to the Murrumbidgee River and is dammed at three points to provide most of Canberra’s drinking water. On the western (NSW) side, the Goodradigbee River flows north through the Brindabella Valley towards Burrinjuck Dam, where it too joins the Murrumbidgee.

A host of birds, reptiles, mammals and insects call the Brindabellas home. On a day-walk you can encounter a copperhead snake, see the runways of broad-toothed rats, watch bounding red-necked wallabies, hear intriguing lyrebird calls and marvel at soaring wedge-tailed eagles. Miles was in tune with the natural world and her books show a love of the wild that was ahead of many other Australians in the early 20th century.

On misty winter mornings when all was damp and dripping, and fragrant as imagination with the sharp sweet tang of the dead leaves, when other creatures were still, then the lyre-bird’s notes rang full and clear through the eucalypt aisles.

– from All That Swagger, by Miles Franklin

Places such as the Birrigai Rock Shelter, located near the Tidbinbilla Visitor Centre, east of the Brindabellas, indicate First Nations people have lived in the area for more than 20,000 years. Ngunnawal, Ngambri and Wolgalu peoples knew the High Country of the Brindabellas and the nearby Snowies well. Others, including the Wiradjuri people, were summer visitors. Summer meant bogong moth feasts, trade, ceremony and intermarriage between language groups. The place name Uriarra in the northern Brindabellas foothills means “running to the feast”.

Names such as this indicate the area’s strong Indigenous heritage, and Indigenous rangers and Elders are vital to the operation of these High Country parks and reserves. There are art sites in Namadgi, east of the range, and stone tools are still found. West of the range the Cooleman Caves area was an important place of burial. Songlines link locations in the High Country, and ACT Parks ranger Dean Freeman, a Wiradjuri man, has told me how major peaks were key elements. Miles had Indigenous characters in her High Country novels and some of her characterisations were advanced for those times.

European settlers began moving into the area from the late 1820s. The Cotter River is named after Irish convict Garrett Cotter, who was effectively exiled in this mountain country for a time, during which he struck up an unlikely friendship with legendary Indigenous warrior Onyong.

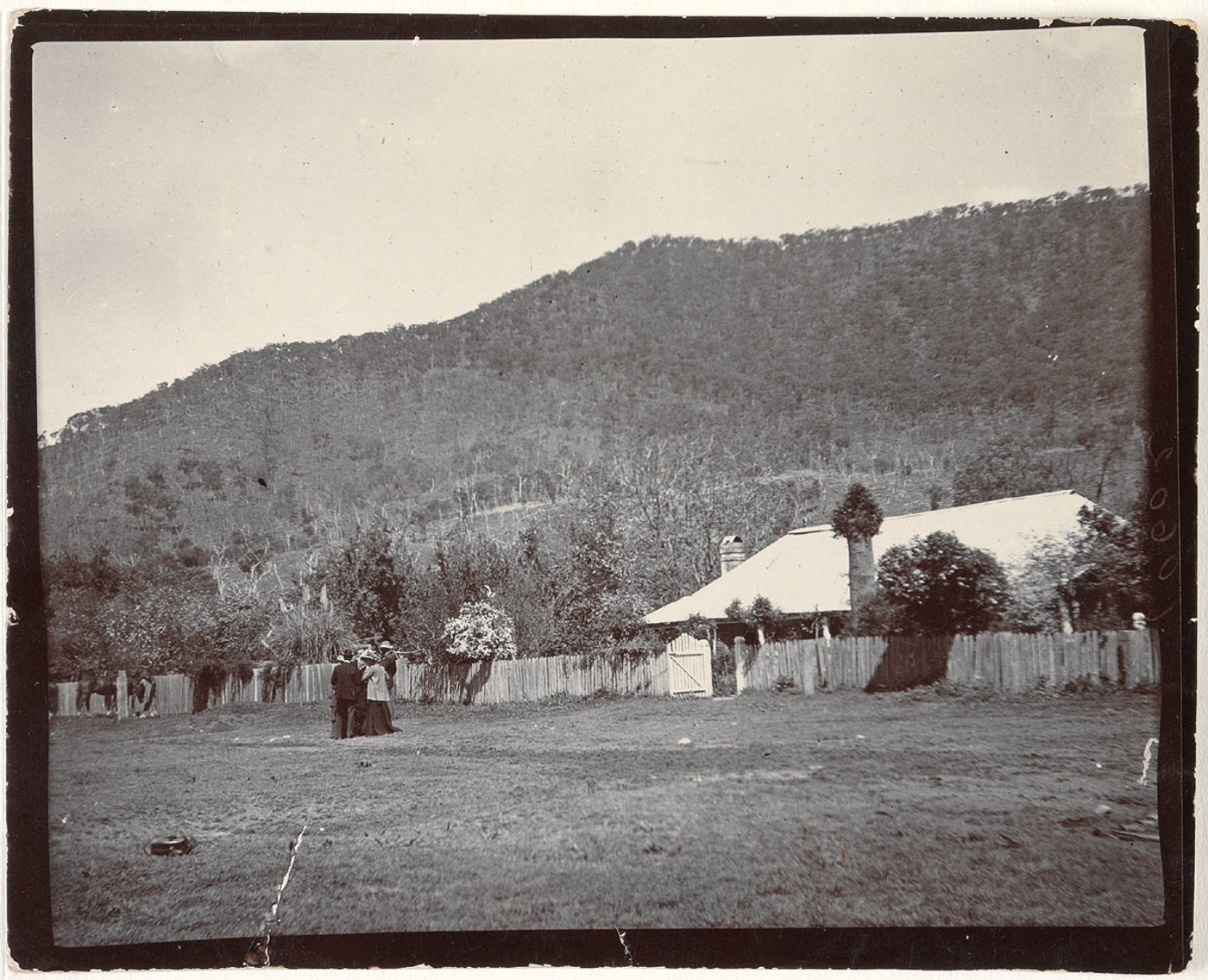

Other settlers arrived in the valleys to the east and west of the Brindabellas. T.A. Murray of Yarralumla had a Brindabella Valley holding in the 1830s. The Franklin family first arrived in 1846 and were well established there by the late century.

William Reid ran a goldmine and hotel late in the 1800s. By the early 1900s, others in the valley included W.P. Bluett of Koorabri, an educated man interested in the classics. Later, Gwen Meredith, author of the famed ABC Radio serial Blue Hills, built a holiday cabin at Koorabri.

East of the range, big changes came with the 1908 decision to establish the new capital city of Canberra there. In 1913 the Cotter catchment was declared off limits to grazing to protect the capital’s water supply. The first catchment ranger in the upper Cotter was Jack Maxwell, who’d worked on Brindabella Station and was married to Miles’s first cousin Ivy. That family link provided Miles with opportunities to join horserides – and even brumby runs – in the ranges during the late 1930s.

He would gaze towards the Australian Alps and collaterals, extending for eighty or a hundred miles around the translucent horizon, and feel as a poet drinking from the fountain of inspiration.

– from All That Swagger, by Miles Franklin

The Brindabella Range is snow country and its native flora and fauna have adapted over millennia, but the snow often took early Europeans by surprise. When Harry Mouat was surveying the new federal territory border along the range in 1914, for example, he recorded that he was unexpectedly snowed in south of Mt Gingera.

But before long Canberra’s new population was making recreational use of the snow, and in 1938 the Canberra Alpine Club built the Mt Franklin Chalet. At that time skis were homemade, there was no snow-clearing on roads and accommodation was basic. An active, but primitive, ski centre, Mt Franklin was popular until Snowy resorts got going from the 1950s. Despite morphing into a ski museum following Namadgi’s declaration, Franklin was the oldest club-built ski lodge on the Australian mainland. Sadly, it was destroyed in the 2003 bushfires, which devastated the Alpine region’s national parks. Royal Military College Duntroon also had a lodge nearby on Mt Ginini during the 1950s–60s.

Miles was born in 1879 at Talbingo Homestead and named Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin. The homestead was later inundated by the development of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme. Her mother, Susannah, nee Lampe, rode through snow from her home in the Brindabella Valley to be with her own family for the birth. Miles’s father, John Maurice Franklin, had a selection just up the Goodradigbee River from Brindabella Station, owned by his brother Thomas. Miles’s grandfather Joseph, born in Ireland, had taken up Brindabella earlier. In time, Brindabella Station became a famous trout-fishing retreat attracting the likes of Banjo Paterson.

Miles’s autobiographical book, Childhood at Brindabella, speaks much of her early years in the beautiful valley. But her family didn’t prosper there, so John, Susannah and the children moved to a property south of Goulburn, where young Miles attended Thornford Public School.

Her writing career kicked off in 1901 with the novel My Brilliant Career, which Henry Lawson helped get published and which was made into a successful film by Gillian Armstrong starring Judy Davis in 1979. Through its success, the book alienated some Franklin family members, who recognised themselves in it. Her uncle George Franklin – brother to John and Thomas – who farmed the family’s original property, Oakvale, near Yass, was particularly hurt. A relation told me recently, “It was clear to George and the broader family that the family the character in the novel was sent to work for as a tutor and cruelly parodied was his. He [George] is said to have commented that ‘she could not have done me more harm than if she burnt all my haystacks’.”

In 1906 Miles went to Chicago to join the burgeoning US women’s labor movement. A few years later she noticed in the offices of Chicago architect Walter Burley Griffin a painting of the Limestone Plains and distant Brindabellas that entrants in the 1911 Federal Capital Design Competition – an international design competition for the proposed city of Canberra – had been sent. She was immediately transported back to the High Country of her childhood, writing to her Aunt Annie, “I thought I was looking out over the ranges towards Brindabella once again.”

After moving to London, Miles spent time with a hospital unit on the Serbian Front during World War I. She was back in London by the 1920s and returned briefly to Australia, including Talbingo, in 1924 and then again from 1927 to 1931. Those visits provided opportunities to gather information about the High Country and her family’s mountain experiences. She interviewed bushmen and relatives, and even sent out questionnaires. From her research she produced Up the Country in 1928, the first of her novels under the pseudonym Brent of Bin Bin. The name Bin Bin probably came from the pastoral leases Bimben East and Bimben West in the mountains.

In 1936, once permanently back in Australia, Miles wrote All That Swagger, a major work of fiction about the High Country. Very successful, and arguably Miles’s best novel, it beat 240 competitors to win the S.H. Prior Memorial Prize. What’s fascinating about this novel is how closely it mirrors the Franklin family’s real story. The main character, Irish immigrant Danny Delacy, has parallels with Joseph Franklin. Both men came from the same part of Ireland at the same time and settled on the Murrumbidgee near Yass. Joseph’s Oakvale becomes Danny’s Bewuck in the novel, and Danny takes up a mountain holding named Burrabinga – very much like Brindabella.

Joseph fell from a horse onto an ant heap, was injured and rescued much later by good neighbours. Danny has a similar accident but loses his leg. Both men went to the Victorian goldfields where Joseph swam the Campaspe River and Danny the Yackandandah. Both were held up by bushrangers on the goldfields. Daughter Della Delacy in the novel rides through the snow to have her baby, just as Miles’s own mother did. Danny’s son Robert takes over Burrabinga in a clear parallel with Thomas Franklin at Brindabella. Whereas the novel’s Burrabinga is festooned with non-paying exploitative guests, the Franklins only charged the fishermen who stayed at Brindabella. Joseph’s wife pre-deceased him, as did Danny’s wife, Johanna. In novel and reality, the first hut at Burrabinga/Brindabella burns down but wife and children are saved.

A significant difference in the novel relates to Indigenous people. Joseph was originally forced out of the Brindabella Valley by the original inhabitants spearing his cattle, and it wasn’t until 1863 that he returned and held the station. In the novel, Danny makes peace with the local tribe and allows them to take a bullock whenever they pass. His attitude is enlightened for the times and perhaps reflects Miles’s progressive attitudes.

There is a mysticism inherent in the mountain environment in the book, expressed through Danny and son Harry. Miles’s love of the mountains is clear, and she writes beautifully of the landscape and its wild creatures. Lyrebirds especially capture her heart, and she often calls them by their scientific genus name, Menura.

To the memory of my Paternal Grandparents whose philosophical wit and wisdom and high integrity are a living legend of the Murrumbidgee.

– from All That Swagger, by Miles Franklin

After the death of Thomas Franklin in the 1920s, Brindabella Station was bought by the Killens, then by the Dowling family who had it for four decades. Miles visited them c.1940: their son John recalled for me how his mother, Annetta, cried tears of laughter on hearing Miles’s tales of life in the USA.

Miles also visited Barbara Tong of Naas, to the east. It was without notice during a mountain tour – perhaps the previously mentioned trip – and Barbara was worried because she had nothing to give her guest for afternoon tea. But Barbara catered nevertheless and Miles later wrote a letter of thanks.

When Miles died in 1954, her ashes were spread on Jounama Creek near her birthplace at Talbingo Homestead.

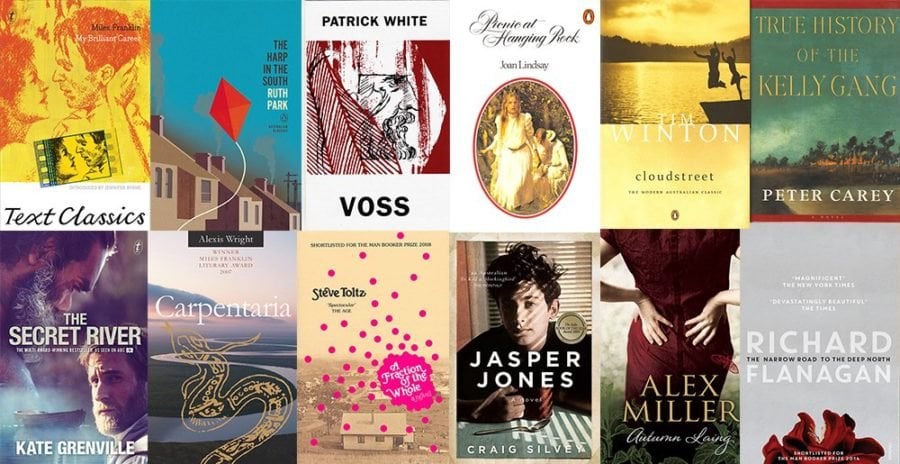

Miles’s most significant memorial is the Miles Franklin Literary Award, one of Australian literature’s grandest prizes. Funded from Miles’s estate under her will, the prize was first won by Patrick White for his novel Voss, which contributed to his later being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Despite some successes, quite a few of Miles’s novels and plays weren’t published during her lifetime, which in many ways was both a literary and a personal struggle.

Due to the annual prize that bears her name so prominently in the media, Miles Franklin is perhaps better known today than during her lifetime. And so, perhaps, are the Brindabellas.