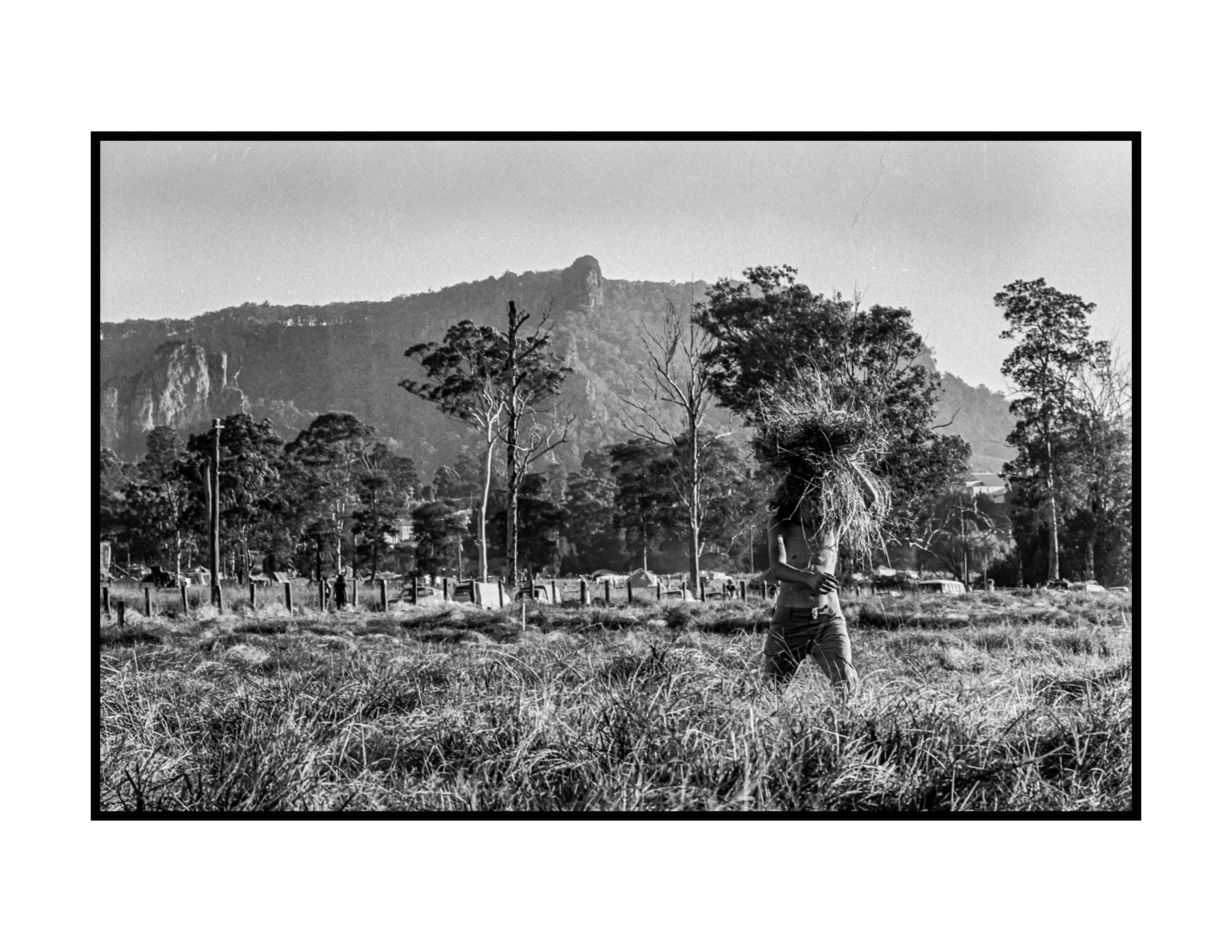

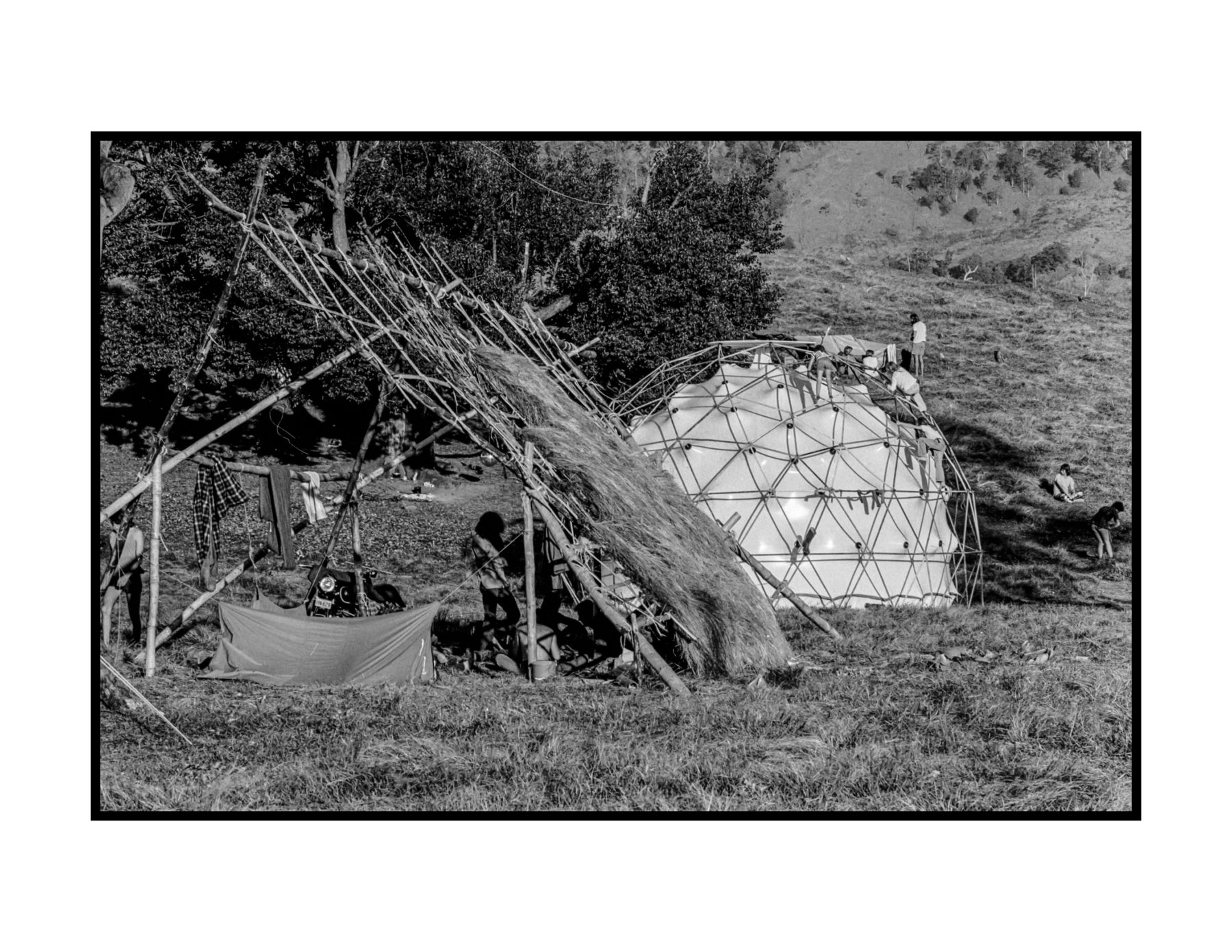

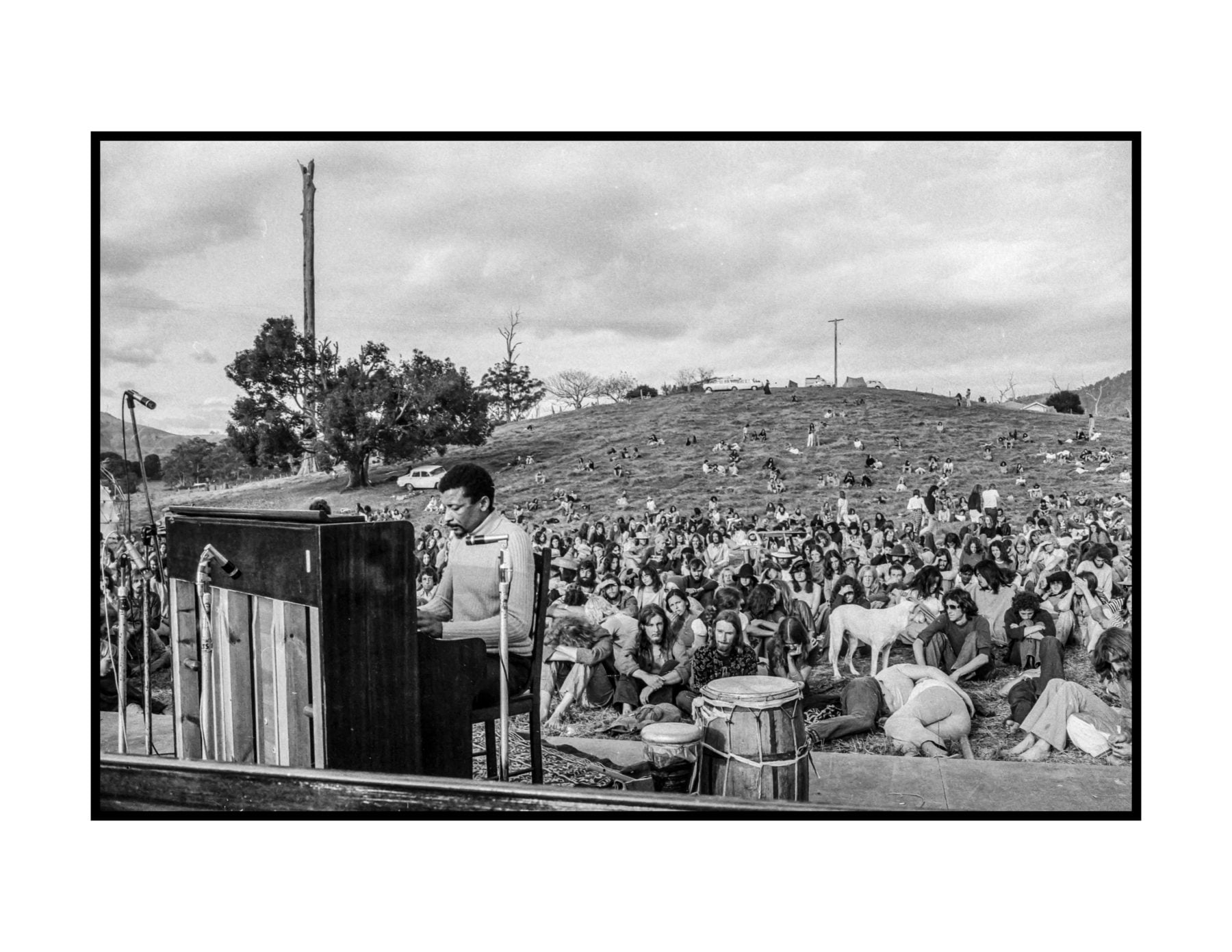

The 10-day festival in Nimbin in 1973 is remembered by many who attended as a critical turning point in their lives, and a flashpoint of deep cultural reflection and communion, which shifted mindsets and also permeated wider society. Unlike the larger festivals such as Woodstock in the USA and Australian music festivals that were taking off in the early ’70s, Aquarius was less about music and more a serious attempt at living sustainably.

While Aquarius drew a smaller crowd than other festivals of the era it had a lasting legacy in terms of social change. Land was cheap and many festival goers never returned to their homes, settling instead across the Northern Rivers, which afterwards became known as the Rainbow Region. They formed hamlets and collectives, driving interest in new ways of shared alternative living across Australia.

It was the first festival known to invite traditional owners, the Bundjalung people, and to open with a Welcome to Country. The festival was ahead of its time in other ways too. Organisers secured funding for cable TV coverage, and TV monitors were set up in Nimbin shopfronts showing recordings from each day. And a dedicated transport system connected the festival with places as far as Western Australia, including a special Aquarius train, The Good Times Express, that linked Melbourne and Sydney to Lismore. Local farm and mill workers joined hippies for events such as a tug-o-war in a Festival Sports Day, new businesses opened in derelict Nimbin stores, and performance troupes such as Magik Caravan toured the local area to promote good will.

While the event transformed the entire Northern Rivers region, it was the ideas and relationships that emerged from these 10 days that altered Australia’s socio-political landscape especially in areas like alternative energy, conservation, multiple occupancy laws and home birth. The NSW Premier at the time, Neville Wran, acknowledged this cultural shift when he stopped referring to the Aquarian settlers as ‘hippy ratbags’ and instead called them ‘concerned conservationists’.

The Aquarius Festival in Nimbin brought together and mobilised previously fractured groups of people who shared the same alternative lifestyle and civil rights beliefs. From this emerged an organised green-activist movement, seeding change and environmental activism across the country. Settlers who stayed on past the end of the festival formed the foundations of a powerful movement that drove many landmark conservation campaigns, including saving the ‘big scrub’, a 300-year-old rainforest, from logging at Terania Creek, northern NSW, and stopping the damming of the Franklin River in Tasmania.

A 50-year anniversary festival will take place in Nimbin this year, from May 12–23.

Look back at where it all started through the lens of four photographers who were at the heart of things.

Peter Derrett, a photographer for Nucleus, the student newspaper at the University of New England in Armidale, NSW, recorded the festival for the National Union of Students. He was introduced to festival co-director, Graeme Dunstan, via Vi Tourle, ex-Nucleus editor, and attended some Aquarius planning meetings at Nimbin’s then derelict Tomato Sauce Factory. Peter taught Drama and English for 36 years at Trinity College Lismore, founded with his wife Dr Roslyn OAM, the Regional Theatre Company, Theatre North. He now works in photographic pursuits shooting for Getty, Opera Australia and various exhibitions.

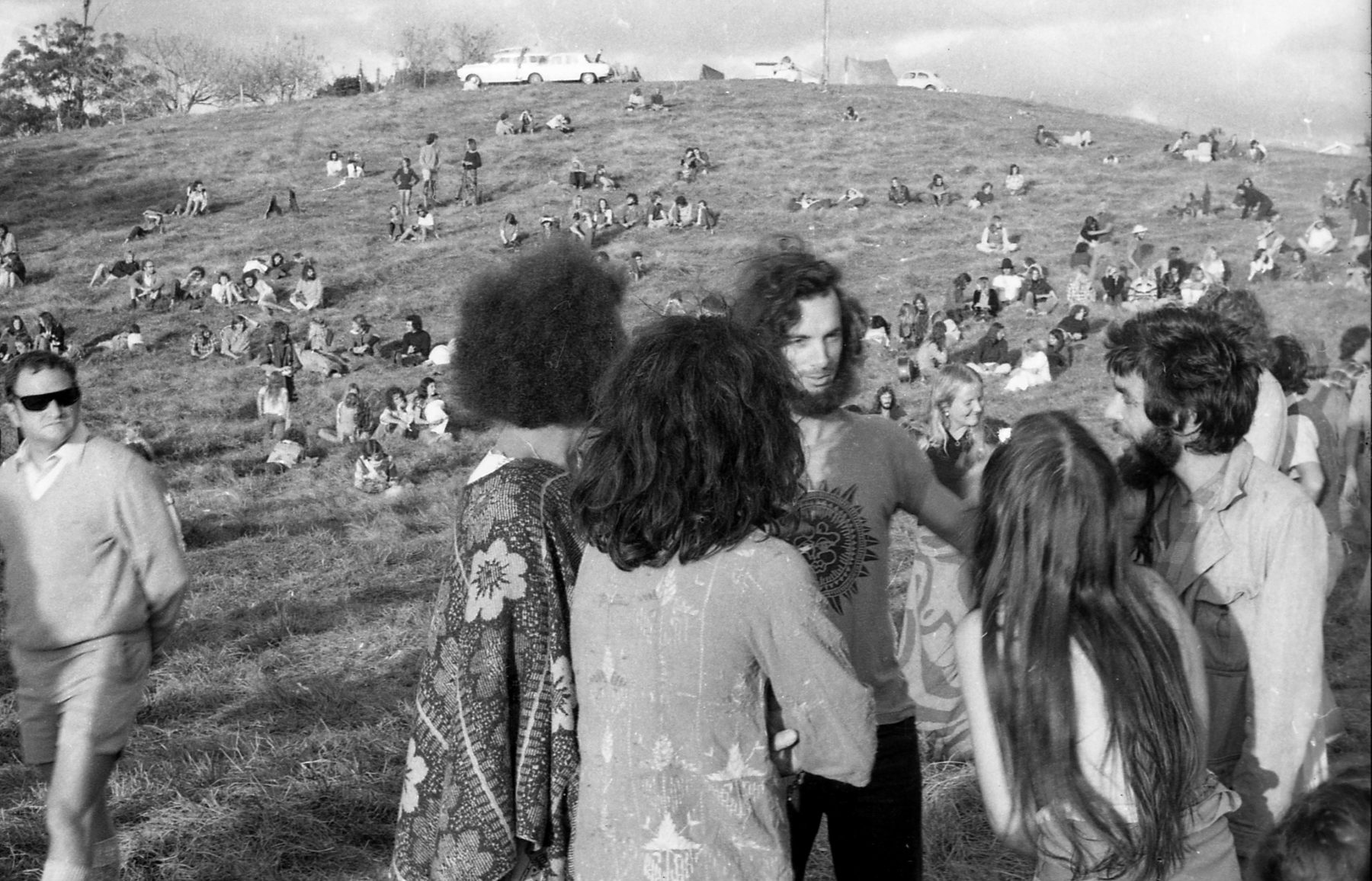

Chris Meagher was living in Sydney in a share house with people who were interested in alternative philosophies and lifestyles. There he met two sisters, Jill and Anna Henry, who suggested he drive them to a festival being held on the North Coast. “So we went on this rather epic trip, it seemed at the time, in my Land Rover station wagon, up north on the old Pacific Highway,” Chris says. “We arrived in Nimbin on the first evening of the festival and I talked my way into being let through to park in the town, on the premise that I was to do a star map for their daily newsletter. This was legit as I was then working at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences running the old planetarium. It seemed as though we had stumbled into a dream world where the largely vacant buildings in the main street had been converted into an electric avenue, where Philippe Petit [a French high-wire artist] dodged through the crowd on a unicycle and then performed extraordinary acts on the high wire.”

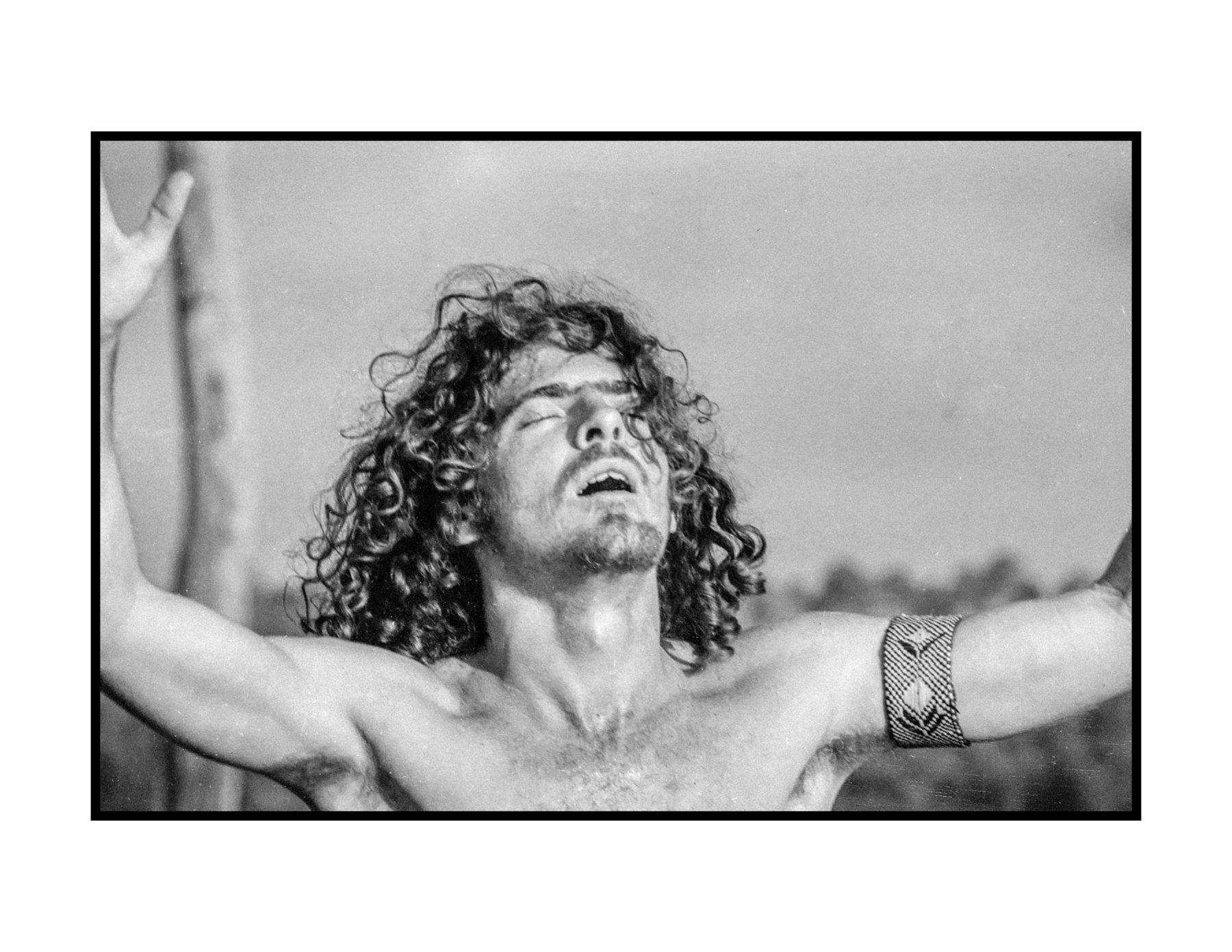

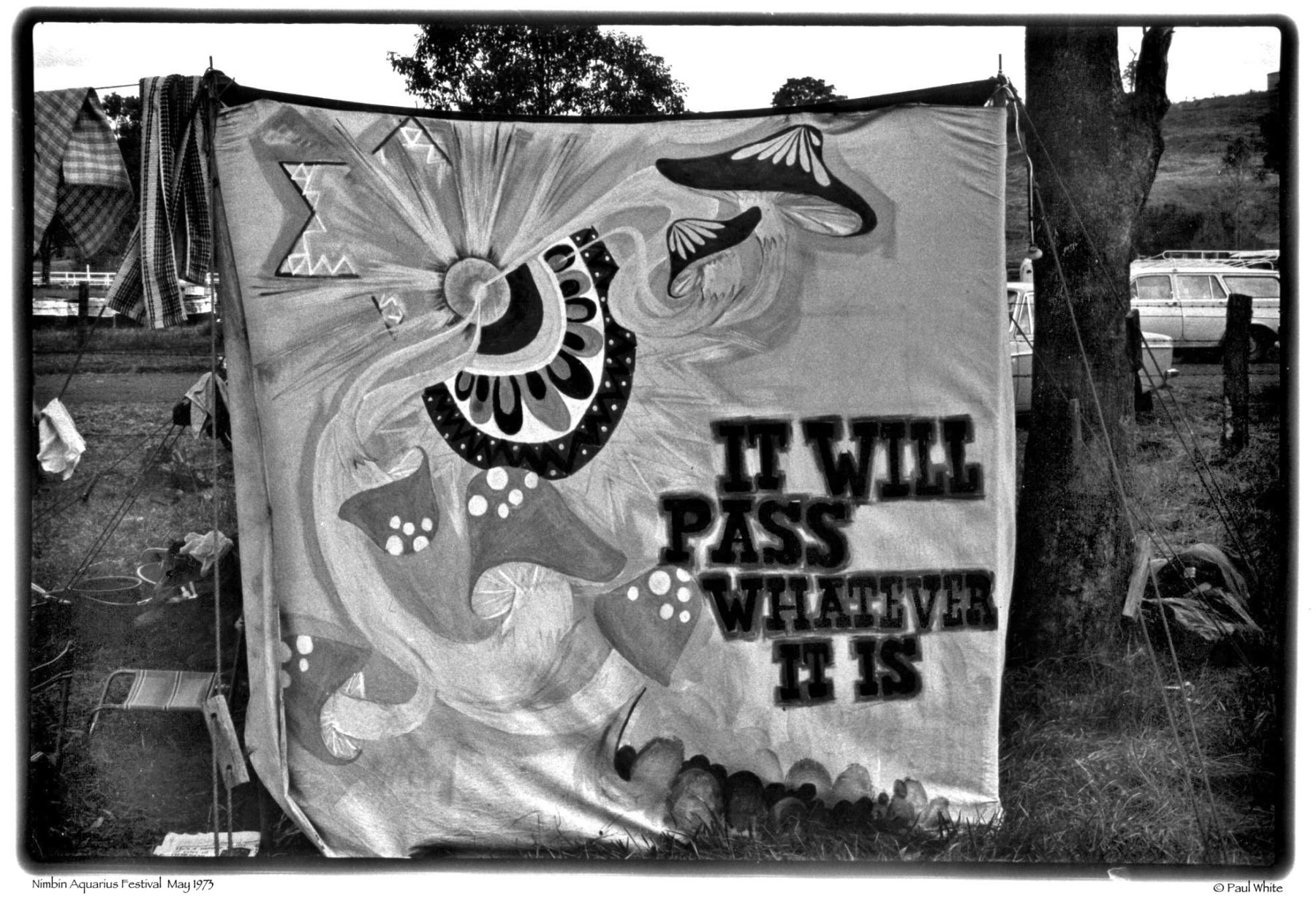

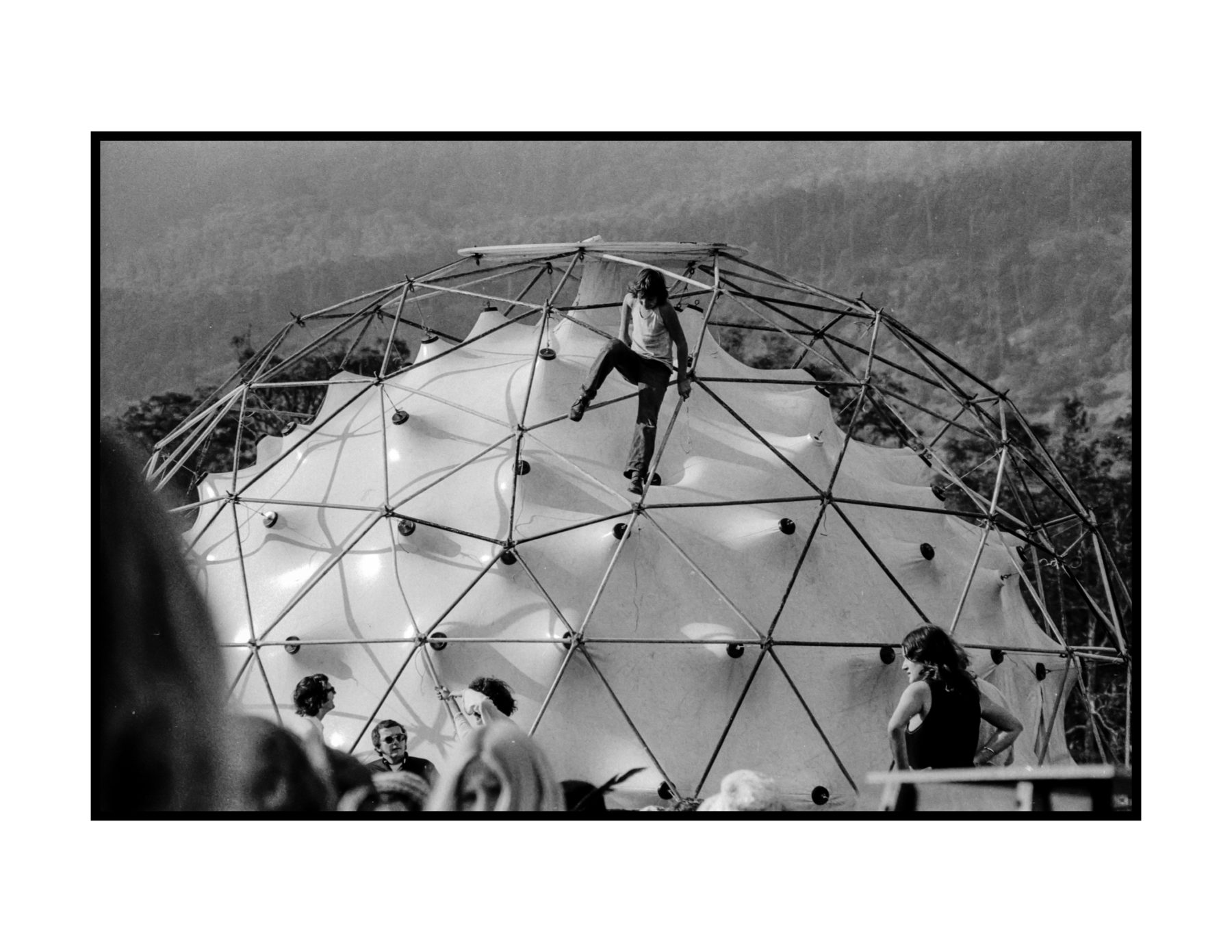

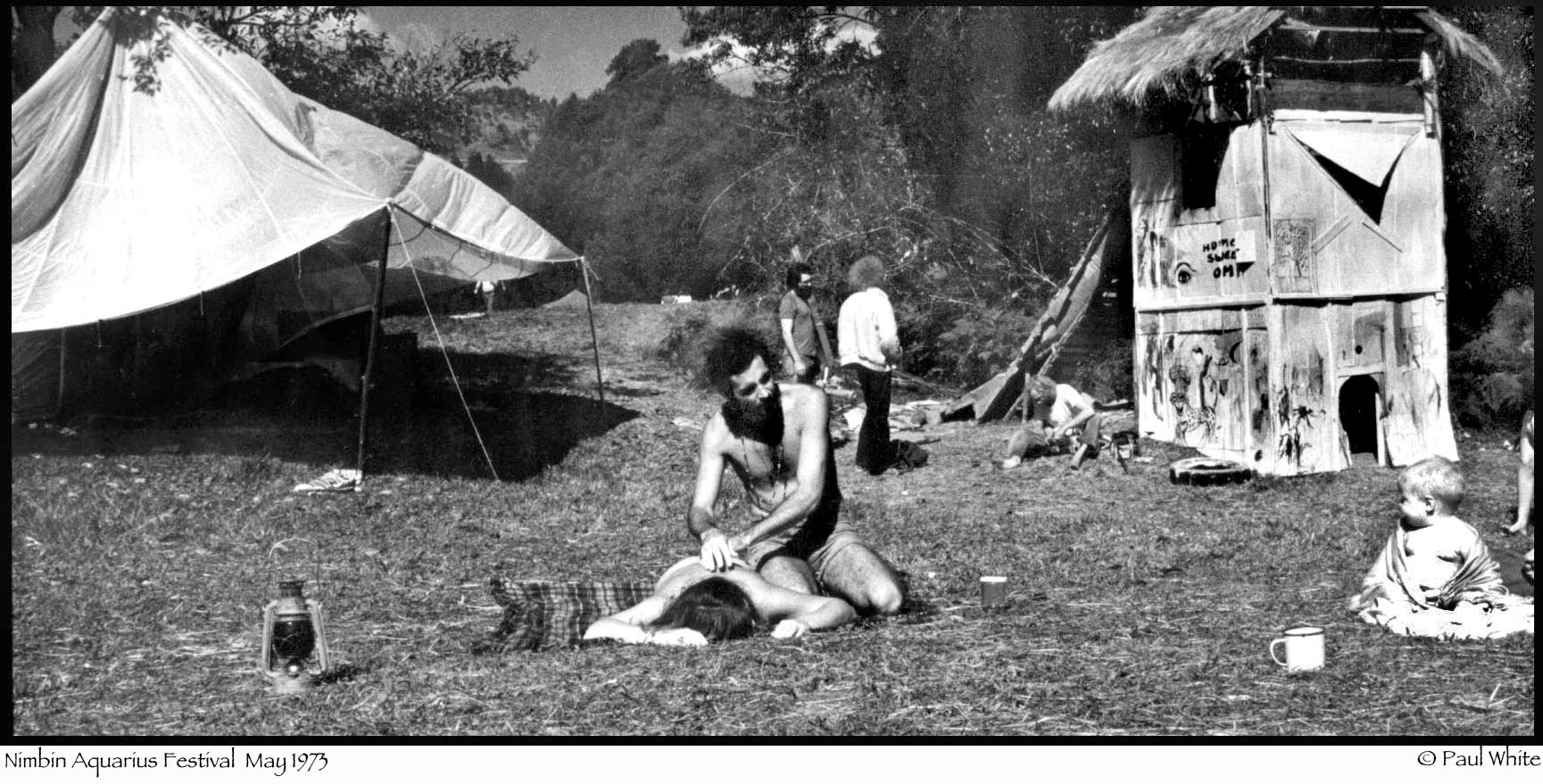

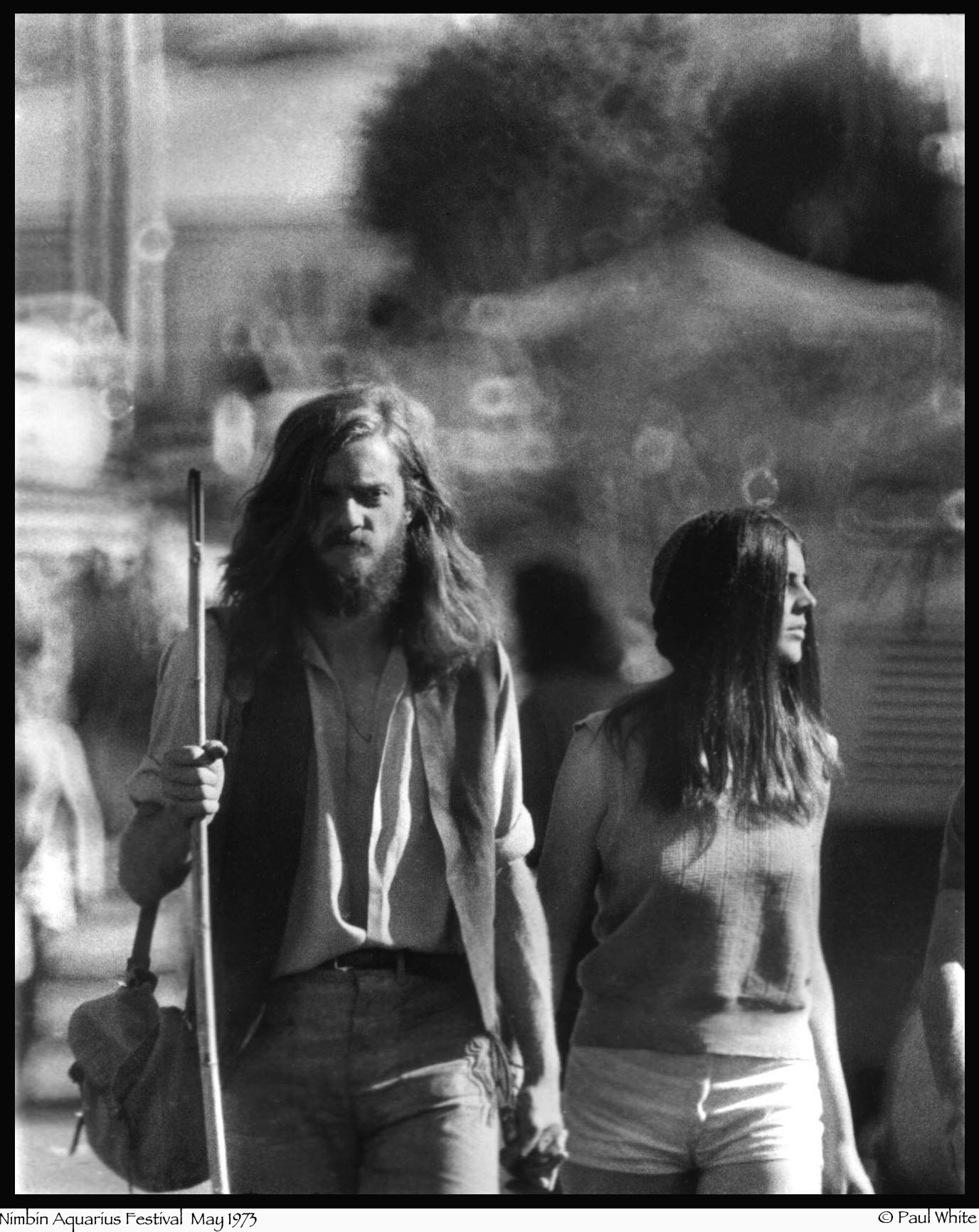

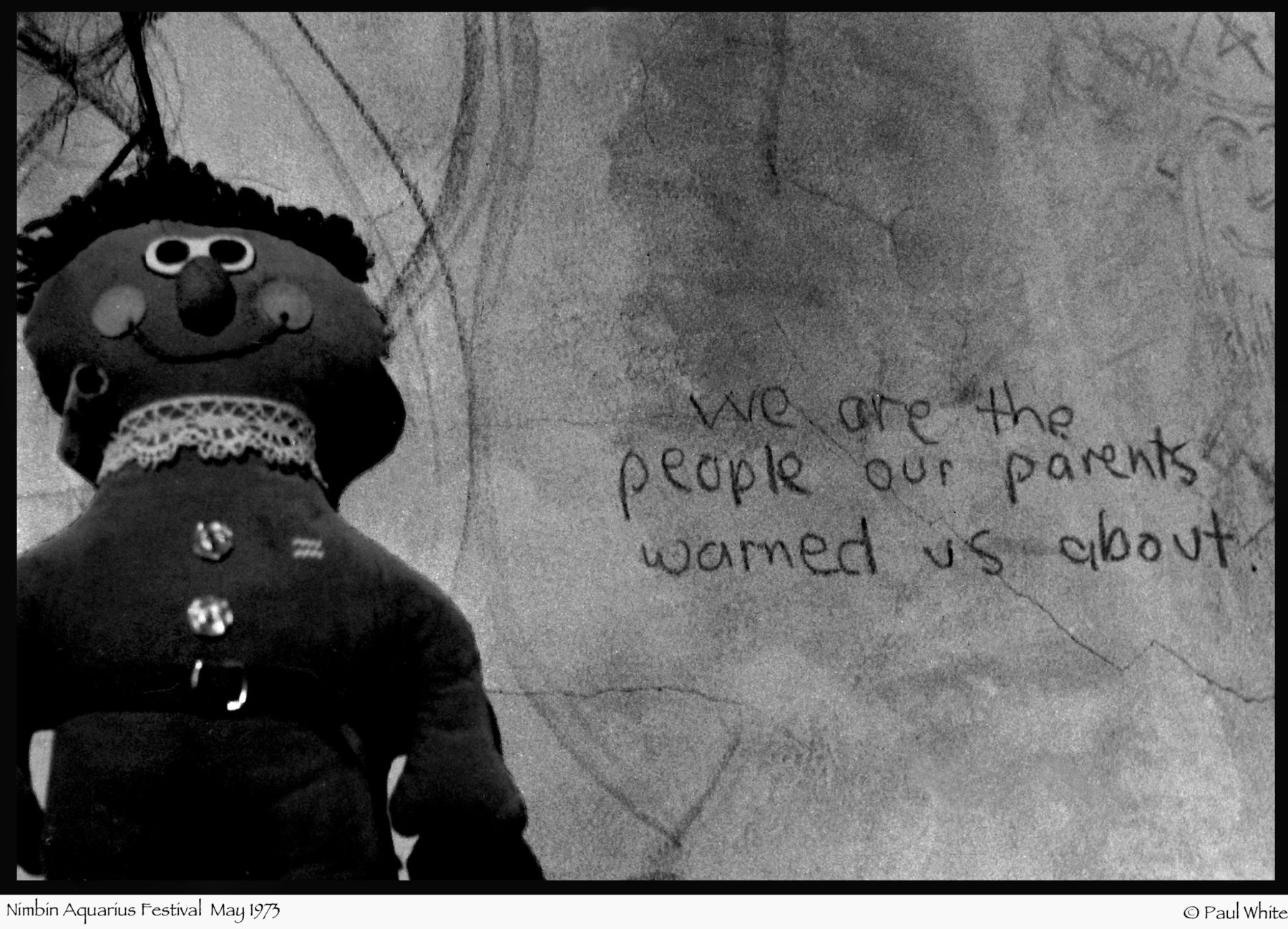

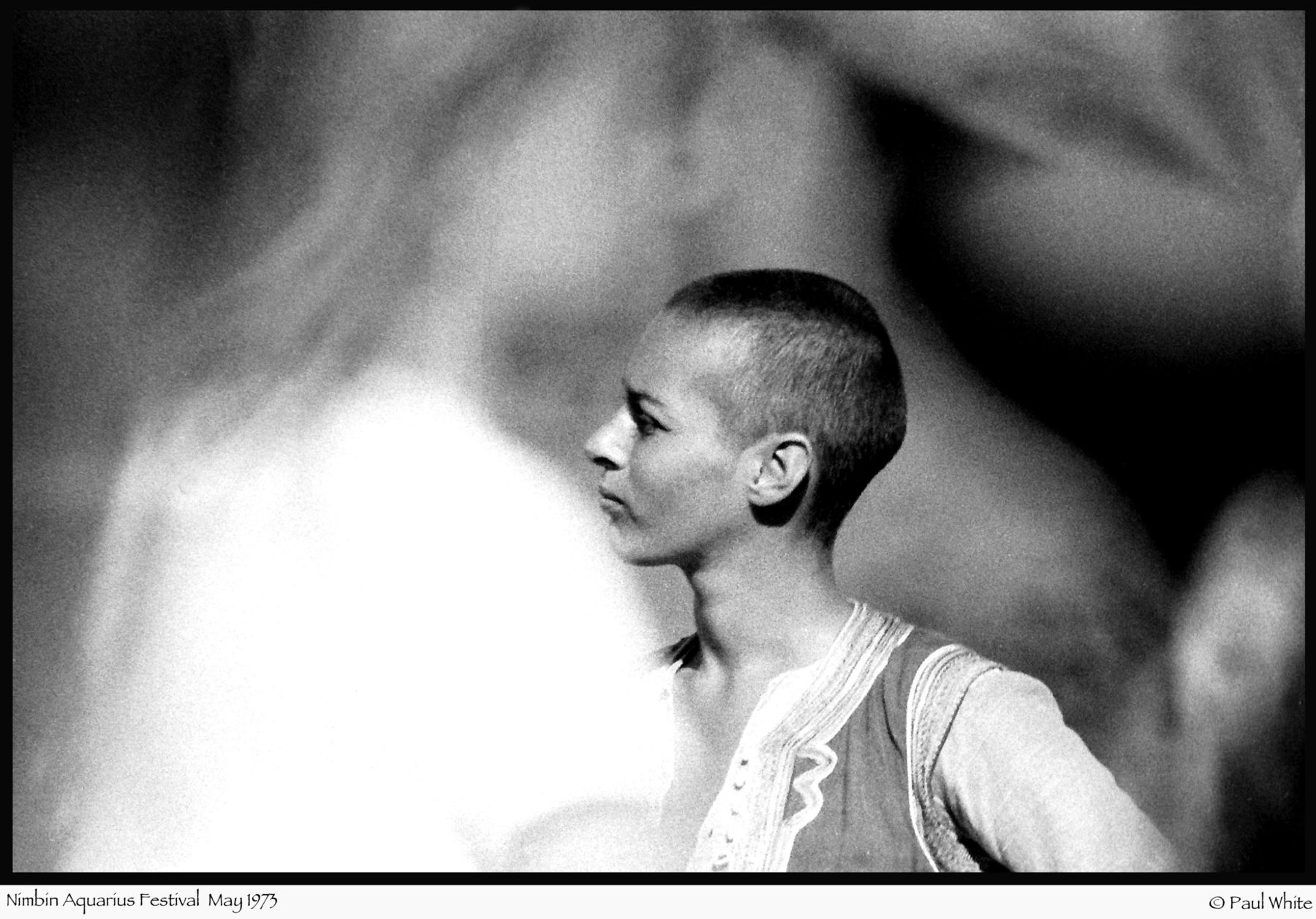

Paul White says he went to the 1973 Aquarius Festival to document the emergence of psychedelic culture: “Occurring at the peak of the psychedelic years in an area notorious for prolific ‘magic mushrooms’, it was also a magical event engendered by high consciousness states and a beacon to all those who turned on, tuned in and dropped out. Artists, mystics and aspiring communards answered the call and came in droves with their families, panel vans and tents. The whole event was a veritable flocking together of birds of a feather, an affirmation of the cultural revolution rippling through the ranks of the rock ‘n’ roll generation. For me, it was group recognition of a new cultural identity, people seeking a peaceful lifestyle away from the big cities that does not harm the Earth. Most of all, the Aquarius Festival was a remarkable exercise in group dreaming, something our Indigenous people know a lot about.” Paul went on to be editor of the grassroots magazine Maggie’s Farm, which circulated NSW and lower Queensland until the late 1980s.

Phillipe Petit’s high-wire walk above the stage, by Chris Meagher.

This festival direction pole was set up in a grassed area at the junction of Cullen and Sibley streets. “The ‘arrow’ at the top swivelled in the wind, the other side was marked with the word ‘SUBJECTIVITY’,” says photographer Chris Meagher.

With thanks to Maired Sullivan, the festival’s information officer in 1973 and later the public relations officer for the Nimbin Progress Association, for her memories and assistance.