The black barnacle-encrusted wedge protruding from the white sand at Carnot Bay on Western Australia’s Kimberley coast is being swallowed by time. It disappears daily as the tide rises and falls, a sand shadow below diamond ripples of water. Few would know this remnant of one of Australia’s great legends is even there – the corroded wing tip of an aeroplane that held great treasure and tragedy.

Carnot Bay’s Smirnoff Beach is far from anywhere, along a rough four-wheel-drive track north of Broome on a pot-holed and washed-out road. There are no signposts to direct you through the dense and overgrown bush. If you make it there, you’ll find a memorial to the victims of a plane crash standing sentinel over the beach and silhouetted against the sheer translucent blue of the Kimberley sky.

Its cross has bowed and a rusted propeller has fallen off the stone plinth. A plaque bearing the names of those who died here 80 years ago, in 1942 – Maria Van Tuyn, Johannes Van Tuyn, ‘Joop’ Blaauw and Dann Hendriksz – has also fallen and lies in the sand.

The sad litany of names evokes images of Maria and her baby, Johannes, fleeing their home in the dead of night as Japanese forces landed in Java in March 1942, heralding an imminent end to their old Dutch East Indies colony.

As the island fell to a new wave of foreign captors, Maria may have considered herself lucky to board the Douglas C-47 aircraft – also known as a Dakota – bound for Australia. Had she stayed she may have lived, imprisoned in a POW camp along with other Dutch citizens. Instead, she was escaping into a great unknown, in the only passenger seat of the Dakota. Johannes might have been asleep in her arms as they headed down the Kimberley coast towards Broome.

The pilot was Captain Ivan Smirnoff, a Russian World War I flying ace turned naturalised Dutch national. Nine men, some pilots needed for the war effort, were huddled in the back.

The passengers were oblivious to the diamonds worth a fortune on board. In war, invading armies always collect the local loot, so thousands of cut diamonds, worth almost £300,000 then, had been pulled from vaults the day before and packaged up for transport to Australia, to be deposited in a bank on arrival. Had the passengers known about the gems, they would have gladly traded them for water in the coming days.

As the dozing passengers approached their destination, Smirnoff saw a dense black cloud of smoke rise on the horizon ahead. He knew it meant Broome had been attacked. Minutes later, Japanese Zero warplanes returning from the raid were in his line of sight.

They began firing on the unarmed aircraft. Smirnoff was hit twice in the left arm and once in the right. As the bullets ripped through the fuselage, a fragment flew from the ceiling and hit baby Johannes in the foot. Maria was shot in the back and another bullet almost severed her left leg. She fell with her child. One of the male passengers, who was also injured, grabbed the baby. Despite being shot multiple times, Captain Smirnoff continued to fly the plane, ducking and weaving to avoid the seemingly endless strafing.

The windows were shattered, the plane was filled with smoke and the engine was on fire. Seven passengers had been shot and three were critically injured. Remarkably, Captain Smirnoff managed to land the plane on Carnot Bay, the wing fire doused by the waves as it rolled through the surf.

It was wet season. The air was thick as soup and the heat suffocating. This was crocodile country and one of the remotest places on Earth. There was no medical help for the dying and injured here.

Within hours of landing on the beach, pilot passenger Dann Hendriksz was dead. Maria regained consciousness, momentarily calling for her son before she too soon passed away. Flight engineer ‘Joop’ Blaauw’s legs had been shattered by bullets. The other survivors bound his wounds but could not stop the bleeding.

Added to the cries of the injured, baby Johannes wailed for his mother’s milk. The survivors were desperately thirsty but had little water. Smirnoff rationed each passenger to 150ml per day, a little over half a cup. He had no idea how long supplies would last between the 10 remaining survivors. A search for water failed to find any. They constructed shelter from the sun using the parachutes from the planes.

Smirnoff sent some of the uninjured men off to find help. But the rugged terrain, tidal creeks and dense bush, combined with severe dehydration, soon got the better of them and they returned. Injured, dehydrated, suffering from searing heat and stifling humidity, without food and unaware if there was any help in this remote corner of Australia, the survivors were desperate. Few knew how to deal with a baby in distress.

Such is the way of history that we don’t know the name of the Nyul Nyul man who discovered two survivors, Dutchmen Peter Cramerus and Johannes Muller, wandering not far from Beagle Bay, five days after the Dakota crashed. Cramerus had lost his clothes crossing a tidal creek and was badly sunburnt.

The Nyul Nyul man couldn’t speak their language but could see they needed help and raced back to Beagle Bay to sound the alarm. It’s to this unknown man that the group would owe their lives. Instead, the accolade for rescuing the survivors went to Brother Basenfelder, a German missionary who helped run the Pallottine Mission at Beagle Bay, and Warrant Officer ‘Gus’ Clinch, who was stationed there to watch the German brothers.

They pulled together a rescue party, including a mule and cart, to help get the injured through the rugged bush. By the time they arrived, baby Johannes was dead. Eight of the 12 people on the aircraft would make it out alive, including Ivan Smirnoff, who was badly injured.

But what happened to the diamonds in the cargo?

Lying in hospital beds throughout the country, the survivors became suspects in the disappearance of the missing diamonds on board the Dakota and were soon visited by Dutch and Australian authorities.

However, none of the passengers were likely to have known anything. In the second week of March, beachcomber Jack Palmer sailed past Carnot Bay in his pearling lugger on his way to pick up supplies in Broome. He’d heard about the air raid from the lighthouse keeper at Cape Leveque. And when he saw the Dakota wreck, he decided to report it to the authorities.

Broome was all but deserted when Palmer sailed into town on his lugger. At least 89 people had been killed in the Japanese attack, and more than half of the casualties were Dutch refugees. Fearing invasion, many of the townspeople had fled in the following days, including the only doctor. Storekeepers stayed, fearing looting, and the police remained on the ground.

Police told Palmer the survivors from the plane had been rescued. He picked up supplies and a few days later sailed north. Riding the tides, Palmer stopped in at Carnot Bay, rowing his tender to the beach. He pored over the plane, taking clothes and a wicker basket. Wedged between a seat on the plane, he found a package embossed with wax seals.

He returned to the lugger with the package. One can only imagine his thoughts as he removed the wax seal and opened the brown leather wallet inside to find thousands of cut diamonds, some as big as seven carats.

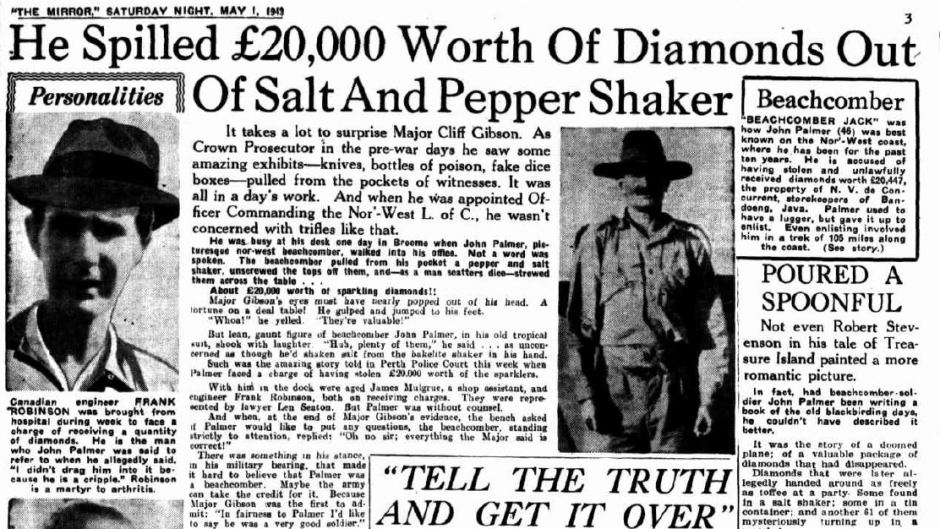

Palmer then headed north, sighting the lugger Aumeric at Middle Lagoon. The larrikin beachcomber couldn’t resist sharing news of his find. He anchored up and camped on the beach with James Mulgrue, a former British pearling captain, and Frank Robinson, a Broome mechanic. The pair had fled after the attack. Palmer shared his discovery and they wondered if the diamonds could be considered ‘salvage’, and therefore rightfully theirs to keep. They knew the treasure could cause trouble when authorities came looking, and discussed whether to keep them or give them back and claim a reward. They agreed that at least a salvage fee should be kept. Palmer gave them both a spoonful of diamonds and managed to spill a few in the sand in the process.

The search was on to find the diamonds, and the men knew it was only a matter of time before word got out. A few weeks after his discovery, Palmer walked into the area commander’s office and poured thousands of diamonds onto his desk. As more and more diamonds turned up in different places, few doubted the 4000 Palmer returned that day were only part of the booty.

Connie Joorida, a Bardi woman from Lombadina, came down to camp at Middle Lagoon where Mulgrue and Robinson had met with Palmer. She scoured their camp when they left, found a film canister full of diamonds and took them back to her partner, Willie, who traded 11 for a tin of tobacco. As diamonds began appearing around the Kimberley, the officer in charge of Native Affairs was sent to recover them. He found 61 and another 15 were handed in to police.

A Chinese tailor who landed from Broome in Perth was met by police who found 460 diamonds in his belongings. More than 6130 diamonds, worth £20,447, were ultimately recovered. But this fell far short of the value of the entire cargo, estimated to be worth almost £300,000. Palmer, Robinson and Mulgrue were all charged with stealing the gems and tried in the Supreme Court in Perth, but they were found not guilty because the judge ruled the temptation would be too great for any man. To this day, the missing diamonds remain unaccounted for.

Over the years, a few treasure hunters have made their way to the isolated beach. Some have souvenired parts of the aircraft, carting off pieces to sell or sit in garages until their origin has been forgotten. And war graves along the west coast have been looted.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Dakota crash. Family members and dignitaries were unable to travel to Broome on 3 March to commemorate those who died, because the WA border was closed due to the COVID pandemic. Had baby Johannes survived, perhaps he might have joined me on the beach at Carnot Bay to remember his mother.