Defining Moments in Australian History: Eureka Stockade

The colonial government announced in early 1851 that gold had been discovered in Australia, near Bathurst, New South Wales, and later that year also in Victoria. It was a catalyst for great change in the new colony. The belief you could dig your own fortune attracted people from across the country and the world. Melbourne lost half its men to the goldfields, crews abandoned ships in port, shepherds deserted flocks; the cry in London, California, Germany and Italy was “off to the diggings”.

Between 1851 and 1860 Victoria’s population increased from 76,000 to 540,000, a massive influx of people that seriously stretched government resources. The colonial budget was already in deficit and finances for services were limited. To raise funds and discourage people from moving to the diggings, NSW Governor Charles FitzRoy and Victoria’s Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe imposed a monthly 30-shilling licence fee on miners, a substantial sum for most. When the easily obtainable surface gold began running out in 1852, the fee became contentious. That year the 35,000 miners on the Victorian goldfields were each on average producing about 5 ounces of gold. By 1854 the miners’ population had almost tripled but production had fallen to 1½ ounces per head.

From 1853 miners began gathering to voice their complaints and sent delegations to present their concerns to La Trobe, but he was unreceptive.The goldfields became tense, with police regularly running “licence hunts” to find diggers who hadn’t paid their fees. Miners claimed police were extorting money, accepting bribes and imprisoning people without due process. Late on 6 October 1854 Scottish miner James Scobie was killed in an altercation at Ballarat’s Eureka Hotel and the proprietor, J.F. Bentley, and some of his staff were accused of the killing. A court quickly exonerated Bentley but the miners sensed a miscarriage of justice because one court member, John D’Ewes, was a police magistrate known to have taken bribes from Bentley. On 17 October a meeting of around 5000 men and women decided to appeal the decision. But after most dispersed, a small group set fire to the Eureka Hotel and were arrested.

During the following weeks, the miners elected delegates who, on 27 November, approached the new

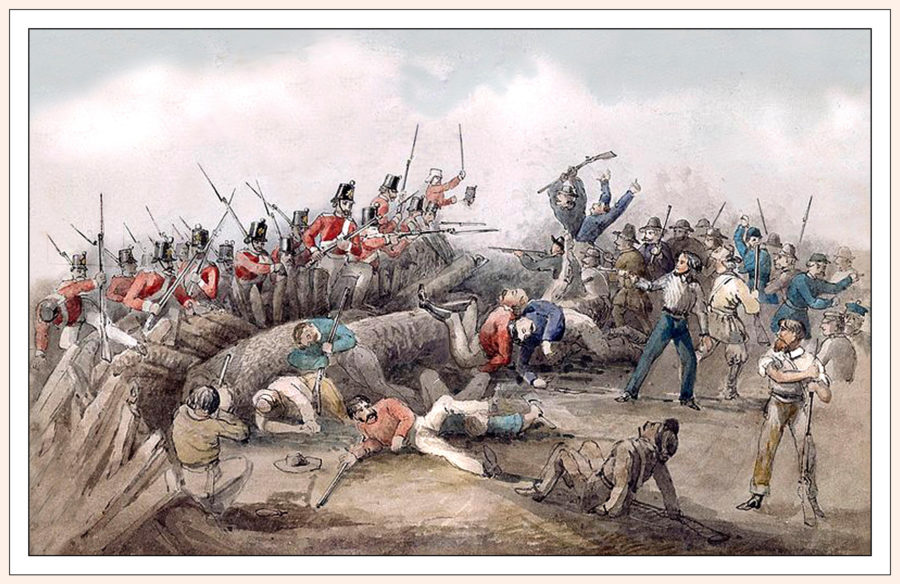

Victorian governor, Charles Hotham, to demand the release of the men who’d torched the hotel. The governor dismissed their grievances and instead dispatched 150 British soldiers to Ballarat to reinforce the police and soldiers already there. The miners responded with another mass meeting on 29 November at Bakery Hill, where the newly created Eureka flag was unfurled. Unsettled by the hostility building among miners, police implemented a licence hunt the next day. That morning, as police moved through goldfield tents, miners gathered to march on Bakery Hill. There, charismatic Irishman Peter Lalor became the protest’s leader and led miners around the Eureka diggings, and in an oath: “We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties.” They then gathered timber from nearby mineshafts and built a stockade.

During the next two days, the crowd remained in and around the stockade, many performing military drills in preparation for conflict. Ballarat goldfields commissioner Robert Rede called for the police and army to destroy the stockade at first light on Sunday, 3 December. That morning almost 300 troopers and police descended on the structure and at least 22 miners (including one woman) and six soldiers were killed. Police arrested and detained 113 miners, of which 13 were taken to Melbourne to stand trial. Governor Hotham called for a Goldfields Commission of Enquiry on 7 December, but Victoria’s citizens opposed the government’s actions in Ballarat, and after jury trials, the 13 rebellion leaders were freed. In March, after the release of the enquiry’s recommendations, the licence fee was removed, replaced by an export duty and a nominal £1 per year miner’s right.

Half the goldfields police were sacked and a warden replaced the many gold commissioners who’d issued the licences, some of whom were corrupt. Twelve new members were added to Victoria’s legislative council, four appointed by the Queen and eight elected by those who held a miner’s right. One was Peter Lalor, who’d survived the Eureka clash with a wounded left arm that later needed to be amputated.

A victory for miners, the Eureka Stockade was a key step to Victoria instituting male suffrage in 1857 and female suffrage in 1908.

‘Eureka Stockade’ forms part of the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History project: