It’s just after 4am when hot-air balloon pilot Nicola Scaife trundles out of bed and pulls on thick, rainbow-coloured socks to brace against the pre-dawn chill. The two-time women’s world champion pads around in the inky darkness, brewing a cup of tea and steeling her mind for the day ahead. Nicola, a 38-year-old mother of two from Newcastle, New South Wales, has travelled across Australia’s wide expanse to plant herself in Northam, about an hour and a half north-east of Perth, in the Ballardong Noongar region. She is one of 30 of the best women balloon pilots on the planet, here to float through Western Australia’s giant skies, vying for the title of world champion, in the fifth Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FIA) 2023 Women’s World Hot Air Balloon Championship. It’s the first time the competition has been held outside the Northern Hemisphere, and it’s garnered even greater anticipation after COVID scuttled the 2020 event meant for Poland.

Competition ballooning for women is relatively new. The first women’s world tournament ran in 2014, more than 40 years after the first open championship, which was – and still is – dominated by men. For Nicola, a win would see her become a three-time world champ – the first pilot of either gender to do so.

“One of my strengths is my ability to keep focus for extended periods,” Nicola says, on day one of the event. “Compared with the last couple of competitions, this is the most focused I’ve been. I’ve won two women’s world championships already, so winning a third would be quite an achievement.”

For most of us, hot-air ballooning is a wistful meander through the clouds, punctuated by oohs and aahs. For competition balloonists, it’s a game of fierce concentration and razor-sharp precision – as much a battle of the mind as an exercise in leveraging wind. Fatigue and a lapse in focus are as likely to undo them as an unforeseen shift in the breeze. Then there’s the stuff that goes unseen. Well before any propane is lit, organisers oversee a labyrinth of behind-the-scenes operations. These include transporting 30 balloons and their baskets to a remote Australian town; negotiating with farmers whose lands may double as landing sites; forecasting conditions that will dictate the competition’s progression; making supervision arrangements for small children whose mothers will float skyward throughout the competition; and feeding everyone involved – the vast majority of whom are volunteers. With no prize money offered, it’s a passion pursuit, and one that’s stolen the hearts of about 621 competition pilots worldwide – nearly 10 per cent of them women.

Little-known sport

Outside of the amateur sport, little is known about competition ballooning. For a start, an event is not a race to a finish line. Instead, balloonists accrue points by completing tasks within time or distance limits. They’re usually given a half-hour window in which to launch, so they have the option of a staggered start.

“You ideally want to be flying in clear air,” Nicola says. “If there are other balloons around, you can quite easily have one fly underneath you and not be able to get where you want to go.”

This often happens near a land target, which is a white, 10x10m X on the ground. Balloonists drop or throw a weighted streamer as close as possible to the target, with points awarded for accuracy. Some pilots navigate solo, others fly with a co-pilot, but all have a ground crew who check coordinates, wind speed and distance, and call the readings through.

As pilots navigate land targets, the balloons look like racing yachts jostling around buoys. “There’s a bit of argy-bargy,” Nicola says, adding that those above must give way to those below. “Some people carry whistles, or you’ll hear people yelling out to let the person below know, so they don’t climb up.” Nicola doesn’t hold back pursuing targets. “I’m quite aggressive with my flying,” she says. “I know what my skill level is; if I can see an opportunity in among some other balloons to get down into an area, I am confident in my ability, and I’ll do it.”

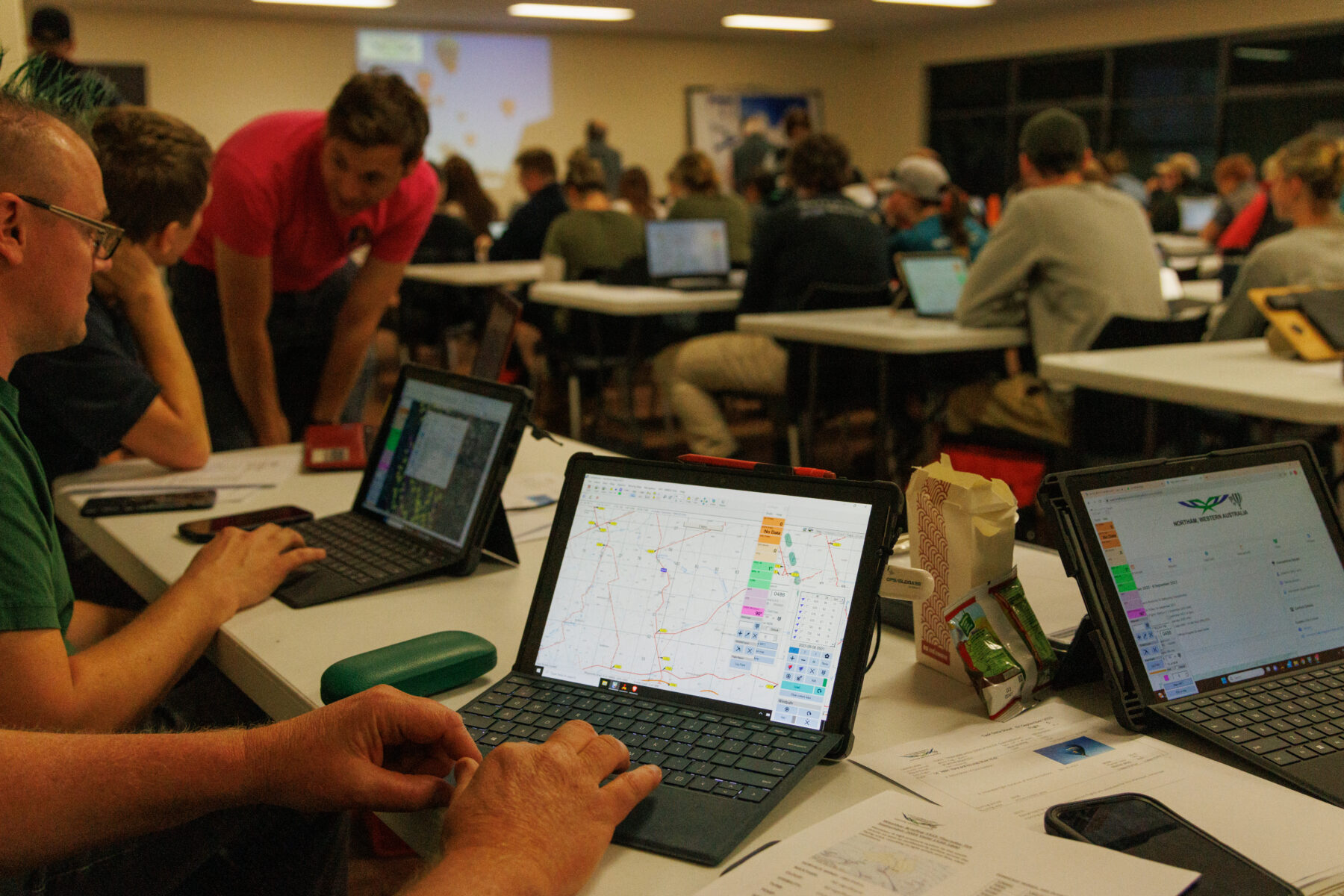

Targets aren’t always physical. Often, they’re virtual. “Some of the flights can get quite technical; it’s a lot of plotting things on computers,” Nicola says. Invisible targets, suspended in the air, are hit using an electronic logger that records the balloon’s position and altitude. “You’ve got to fly, but also know when to press a button to drop an electronic mark,” she says. Clearly, there’s no steering wheel: the key is to travel different directions by riding winds at different altitudes. Northam’s well-suited winds are typically calm on the ground of the Avon Valley – particularly in the cool before dawn and at sunset – and faster above. In 2023 they reach up to 70km/h during the competition.

The science of wind

Understanding the wind’s whims is fundamental for every pilot. That’s where meteorologist Don Whitford comes in. At 3am – a full hour before Nicola starts her day – Don’s alarm sounds. As he rubs sleep from his eyes, the volunteer weather sleuth pops open his laptop and dives into data published by the Bureau of Meteorology, where he’s worked for 55 years. His eyes feast on synoptic charts, dew points, highs, lows and fronts, as he compares the data and assesses the conditions ahead for the day. By 3.30am, he’s in Northam’s ballooning headquarters, the Aero Club, musing over what information to include in his twice-daily briefings.

The first briefing is delivered at 5.15am. The balloonists hang on his every word and leave clutching the printed weather sheets he provides. “There’s an awful lot to look at,” says the Melbournian, who’s donated his time to ballooning events for the past three decades. “In the Bureau, we have big, triple screens with maybe four products on each screen, and another one to prepare text on,” he says. “It’s all done on the one laptop here. I’ve got windows open all over the place.”

Don’s presentation includes the latest radar and satellite imagery, as well as a weather chart and a forecast for the flying area predicting cloud base, visibility, surface winds, air pressure, and more. Final readings are collected as close to deadline as possible. “It can change from minute to minute, especially the lower 200ft of wind,” Don explains. “Temperatures might change a bit and that results in a change in wind direction at those critical lower levels – that’s called drainage. The air is like a fluid, similar to water; it flows around buildings, down hills and along creeks, and pilots can steer using that.”

The bearer of the crunch-time data is a small, battery-operated tool known as a Windsond. The device is launched skywards to gather wind and temperature calculations in real time. Don takes its final transmission – sent via automated SMS and email – just before 5am.

“When it’s high enough, a button is pressed and the device plumets to earth,” he says. “Then a team goes to the paddock and picks it up. Sometimes they’ve got to walk through swamps, or crops, or the bush to retrieve the thing.” The devices cost about $150 each, and only weigh a few grams. “It would fit inside your coffee cup,” Don says. “It’s a great invention.”

In all, Don is dedicating about 10 full days of work to this year’s competition, something he calls a “love job” for a sport he’s become passionate about. “It was the micro meteorology that got me interested to start with,” he says. “Now it’s the people. It’s such an interesting crowd.”

A blood sport for early risers

At about the time Nicola is up sipping her tea, I groan and hit the snooze button on my alarm. I’m reluctant to emerge from under the covers in my room at the Farmer’s Home Hotel in central Northam, but the promise of an extra-special hot-air balloon flight wills me from the warmth. By 5am, I’m pulling up at Windward Ballooning, where AG’s photographer Max Mason-Hubers is perkily at the ready, laden with lens bags slung over both shoulders. We, and a group of excited spectators, are joining a commercial flight to chase the competitors as they scatter like confetti into the sky.

“Ballooning turns into a blood sport when a competition is on,” says the driver of the Windward Ballooning bus, laughing, as she deposits us in a grassy paddock where the competitors and their crews are busily preparing, like ants before a storm. I sense she’s only half-joking.

At 5.40am, the field is lit up like a Christmas tree: hazard lights flash yellow from every vehicle, each one towing a trailer – mostly borrowed from local farmers – with a wicker basket on the back. Bulky balloon envelopes are unfurled as stars twinkle overhead, the half-moon glowing through a blanket of cloud. Inflation fans pop and chug like propellor aeroplanes warming up. They pump air into gaping balloon mouths held open by crew. When the balloons are nearly full, gas burners start spurting, sounding like whales puffing air through their blowholes. I notice black, party-sized helium balloons floating vulnerably through the air; they provide last-minute indications of wind direction and speed before the balloons take off. After the yellow five-minutes-to-go flag is swapped for a green one, competitors begin to levitate into the skies.

Watching the bulbs of primary colours fade silently into the wispy clouds is a wondrous, pinch-me experience. We ascend, following along behind the 30 pilots as they pass over Northam’s farmland, the green of maturing wheat contrasting with the highlighter yellow of blooming canola. We coast by a row of 16 towering grain silos and over a long line of manufactured dams that act as mirrors, reflecting low-flying balloons. The clarity of the acoustics up here is astounding – I hear sheep baa, magpies chortle and dozens of town dogs bark as though they were beside me. Coasting over the town’s historic main street grants a surreal thril

Our pilot, Dom Bareford, is a 30-year-old British national champion, who won the 2018 World Hot Air Balloon Championship held in Austria. Like many competitors, he comes from a passionate ballooning family: his father is a two-time world champion and nine-time British national champion. Dom’s here to support his 32-year-old sister, Steph Hemmings, who is competing in her first women’s world event, while on maternity leave from her job as a hospital doctor. “She fed her four-month-old baby before take-off,” Dom says, noting that Nicola Scaife was doing the same thing for her own baby at the 2018 event.

Juggling the sport with family commitments and the fragmented sleep that comes with having young children is something many women competitors talk about. “Steph’s pretty good at staying cool under pressure, but it can get tough as the week progresses and fatigue sets in, especially managing a newborn,” Dom says. “It’s a bit like batting in cricket: you’ve got to have technique and ability, but the biggest thing being tested is your decision making.” Dom says the intense pressure pilots feel is often underestimated. “It looks like a mundane sport with balloons just going up and down, but it’s very adrenaline-packed.”

Critical ground support

The rush of ballooning isn’t exclusive to those in the air. Each crisp morning during Northam’s ballooning season – from April to October – farmer Kathy Patterson stretches her limbs and wanders out to her verandah to marvel at something she’s been looking at since she was 10 years old. “How many years have I lived here, and I still stand out the front and watch them fly over?” she says, laughing. “I get excited every 1 April, then I feel sad at the end of October when they stop flying for summer.” The 430ha sheep and cropping property Kathy grew up on has been under the flight path since Northam caught the ballooning bug more than four decades ago. “For my 50th, my husband sprayed a big 50 in the crop, and he surprised me with a balloon flight over it,” she says.

Up to seven balloons at a time fly overhead on a regular basis, so when Kathy heard 30 would hit the skies for the Women’s World Championship, she was beside herself. “I was like a little kid in a candy shop. I get so excited,” she says. “It can be really magical with the mist in the valleys. We’ve got a million-dollar view.”

Kathy, her fifth-generation farmer daughter Joanne Smith, and countless others have agreed to offer their properties as spontaneous landing sites, should the balloons need to come down. It’s not ideal – crops can get damaged by baskets, and retrieval means paddock traffic, which equates to lost income – which is why volunteer farmer liaison Brendan Parker spends months visiting landowners to seek permission before the ballooning season. “I’ve grown up with balloons in the sky every winter and I love the spectacle. They take the breath away, even now,” he says. “I’d say 99.9 per cent of landowners feel the same and will happily have them launching or landing in their property.”

Pilots are well briefed that pasture paddocks, rather than crop fields, are preferred emergency landing spots. “At the pilot briefing, it’s made very clear they’re not to land in a crop unless they absolutely have to – they will be penalised,” Brendan says. “They are allowed to land with sheep in the paddock,” he adds. “We tell them to look for gates, don’t push the sheep around, try and find a farmer to say who you are as a courtesy, that sort of thing.”

Of course, there are exceptions to the rule. “The advice is given, but there’s always a chance the wind might change or there’s a powerline in the way,” Brendan says. On this point, Kathy is resolute. “If you have to do it, you have to do it,” she says. “These are all talented women, so I’m very confident.”

Each of those talented women has had to work hard to ensure they have a balloon to fly in. With competitors hailing from 13 nations, including Japan, Lithuania and the USA, arrangements for transporting gear started early.

“A lot of pilots bring their own envelopes, then borrow the basket, burner and tanks,” says Australian team manager Sean Kavanagh, whose family runs Kavanagh Balloons, the only balloon manufacturing business Down Under. They, and many Australian pilots, have loaned equipment to visitors.

“Most people will have done it for the cost of the freight to get it here,” Sean says, explaining that it costs about $1000 to send a container back and forth across the Nullarbor. “The biggest challenge we’ve had is explaining to competitors that the majority of the gear has to come from the eastern states. They’re like, ‘It’s only across one country.’ We say, ‘Well, no, to get it from Sydney to Perth, it’s about the same distance as Amsterdam to Istanbul’,” Sean says. “For a lot of people, particularly Europeans who normally just drive across a border to another country, it’s a bit of a shock.”

Competition, camaraderie and passion

It’s day five of the Women’s World Championship, flight six of seven, and as the dawn sun casts a golden glow over Northam’s farmland, a winner has emerged so decisively a name has already been called. Nicola Scaife has achieved her dream of becoming a three-time world champ. After earning points across 20 tasks, Nicola drops the winning marker and radios to her crew that they’ve done it. “It’s an incredible feeling – real intense emotion,” she says. “There’re a lot of personal things that go into these long-term goals and journeys, so it means a lot.”

Upon accepting the trophy, Nicola publicly retires from competition ballooning, the sport she’s pursued for the past decade. “It was always my intention,” she says. “Life changes, things happen, and for me it just felt like a good time. I’m not going to stop ballooning, but it’s bittersweet to have that ending.”

The early victory allows Nicola to approach the competition’s final flight in a different headspace, dropping her characteristic laser focus for the joy of just taking everything in. Fittingly, it happens at sunset. “I was standing on the launch site surrounded by all these women from all around the world,” she reflects afterwards.

“We come together with this combined passion, so I was soaking it all up with an appreciation for what we all get to do, and for each other too. It’s this fierce competition, but there’s so much camaraderie.”

Visiting Northam

Brought to you by Shire of Northam

Located in the heart of the picturesque Avon Valley, Northam is home to a diverse range of tourist and heritage attractions, including hot air ballooning, cultural experiences, wildflowers, tours & trails, historic buildings, horse racing, white swans, and much more.

Northam comes alive during the cooler months as we welcome visitors for the ballooning season and the annual Northam Motorsport Festival in April – the classic car race where spectators can witness one of only two street circuits events left in Australia.

The famous Avon Descent sets off each August from Northam and festivities begin with the Northam Bilya Festival street parade, a community event full of colour and spectacle.

When events aren’t in full swing you can stroll across the Northam Suspension Bridge – the longest pedestrian suspension bridge in Australia that spans the Avon River. Visitors can often catch a glimpse of our majestic swans in the only remaining habitat white swans breed naturally in Australia.

Nestled seamlessly over the riverbanks is Bilya Koort Boodja, Centre for Nyoongar Culture and Environmental knowledge offering an immersive, interactive journey guided by local experts.

Northam is proud of its unique culture and diversity and its history is showcased in the many heritage buildings doted through the quaint streets alongside modern murals and a plethora of fine food and dining options.

Whether for a day trip or a weekend getaway, Northam promises something special for every visitor, making the Avon Valley an ideal destination for your next adventure.