ONE rain-lashed January night in 1929, a lonely and defeated Italian immigrant by the name of Valerio Ricetti arrived on the outskirts of Griffith, New South Wales, and sought shelter in a rock overhang. Another depression-era drifter seeking work, he’d walked 120km from Hillston on the Lachlan River to get there.

Flat broke after a string of temporary jobs and in moral despair having been heartbroken, beaten up, robbed, swindled and jailed, he was at the end of his tether. He was disillusioned with society and wanted no further part of it. When he emerged the next morning and surveyed the deep recess in the rock and the rich soil, abundant wildlife and water sources nearby, then fruit farms stretching to the horizon, he saw the opportunity of a life apart.

The site upon which Valerio had chanced, Scenic Hill, was a remote southern outpost of the lengthy McPherson Range. Its south-facing flank comprised a line of sandstone cliffs with deep overhangs and a magnificent panorama across the Murrumbidgee flood plains.

Griffith in 1929 was itself scarcely 13 years old, designed by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin as part of the new Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area and populated predominantly by Italian immigrants.

The burgeoning farming settlement was on its way to becoming a major fruit supplier, and its small urban centre reflected the origin of its citizens with pizza and gelato shops. Valerio, however, unwilling to venture the 2km into town for more than eight years, remained unaware of the proximity of so many of his countrymen and women.

Once he’d decided to make the area his home, Valerio drew on the skills he’d already gained during the course of his life. Back in Italy he’d been apprenticed to a stonemason until, at the age of 16, he emigrated to Australia.

From South Australia he travelled to Broken Hill where he found employment at a mine, but left when spurned by a local barmaid called Joyce, whose memory would haunt him for the rest of his days. Then he became a transient labourer – a swagman – taking whatever work came his way – fruit picking, fencing, prospecting. During the next 15 years he ranged around the lower Murray–Darling Basin, eventually turning up at Burrinjuck on the Murrumbidgee.

Fed up with (and intent on avoiding) his fellow humans, Valerio dreamt of a solitary life, buying fishing gear and traps to provide sustenance. Wandering 500km west and another 200km north-east, mostly on foot, had taken him to Hillston, from where he’d eventually arrived at Griffith.

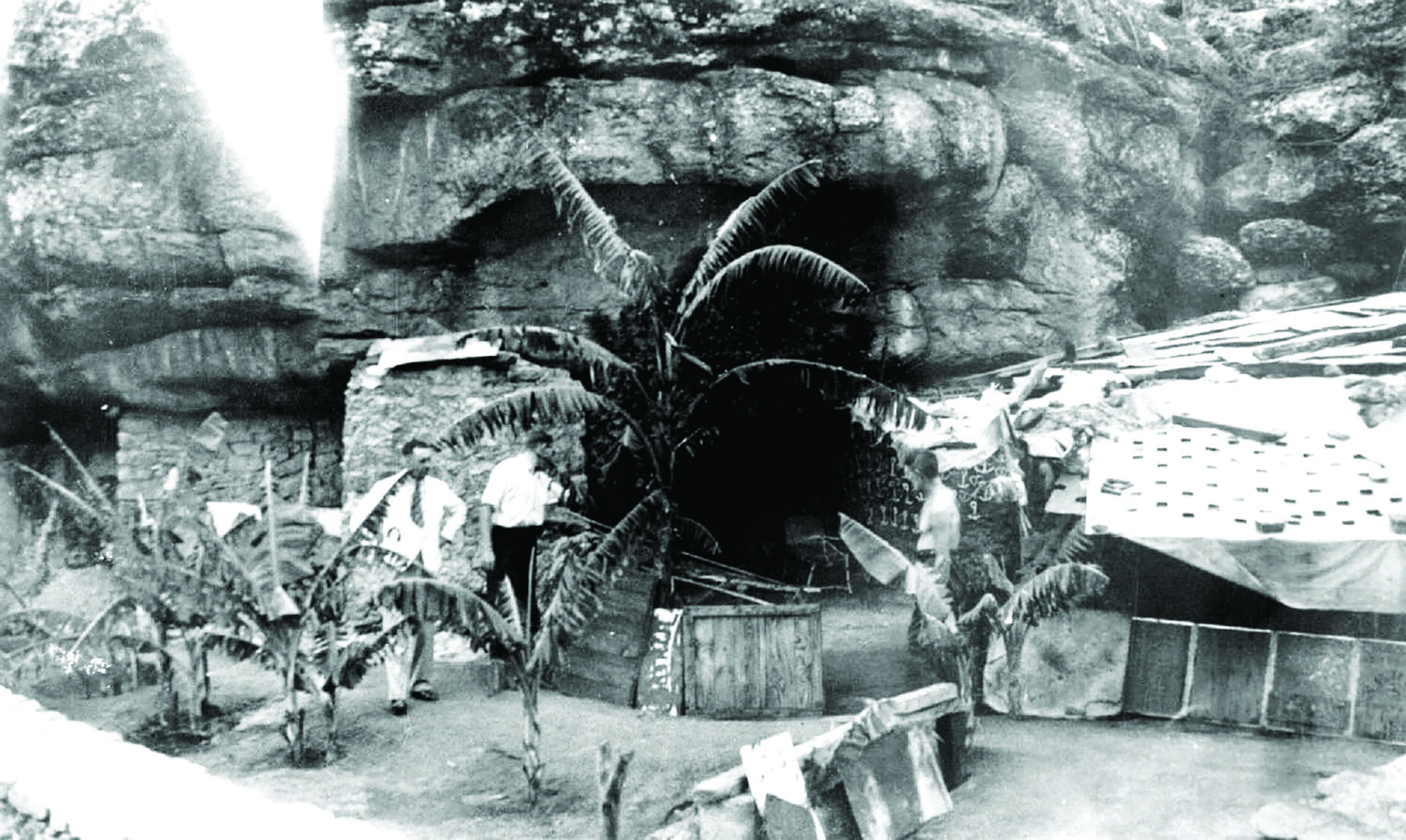

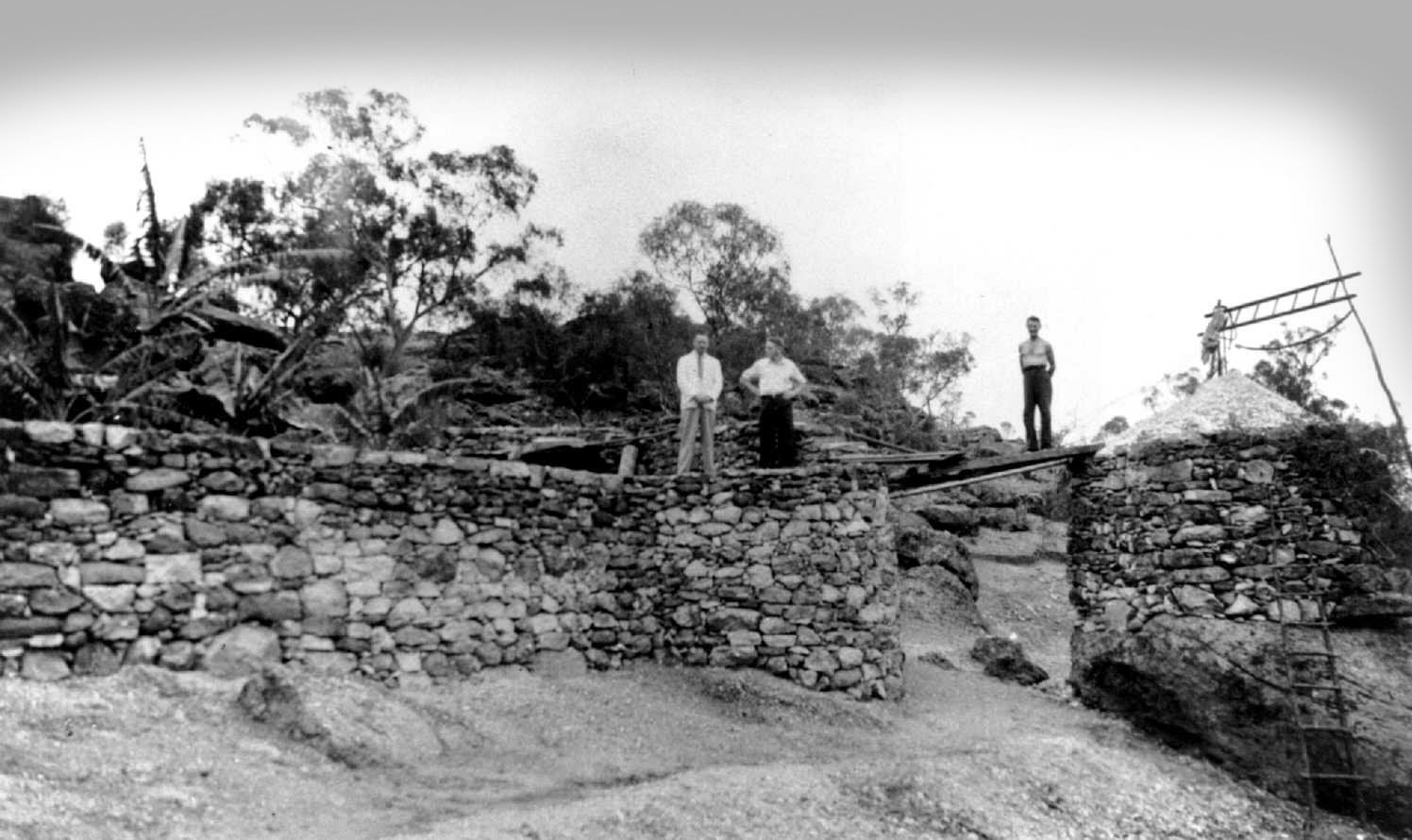

After deciding to stay on Scenic Hill, he rooted out some old tools at the town dump, including a shovel and mattock head for which he carved handles, and began building. He enclosed the deepest overhang within dry-stone walls and installed a fireplace. He built terraced gardens along the eastern side of the hill, interconnected by stairways and stone pathways, to plant crops. He trapped rabbits and hunted wild pigeons with a homemade catapult, and supplemented his diet with pilfered fruit and vegetables. He constructed retaining walls and stone-lined cisterns to capture rainfall run-off. He moved an incredible amount of soil during the next two years as he laboured undisturbed, working mainly at night to avoid being discovered by the townspeople.

While his hideout remained relatively hidden from casual inspection for a while, the residents of Griffith eventually began to notice the changes on the hill. When people came to investigate, Valerio made himself scarce, retreating to one or another of the secret caves he’d built for that purpose.

When his living quarters were discovered, stories of a mysterious hermit began circulating, but he remained elusive for the most part. Little by little his mini empire expanded.

He grew figs, grapes and peaches, as well as lettuce, sweet peas and tomatoes. The town dump provided him with old clothes, plant bulbs and seedlings, which he sowed in his gardens, never knowing what they’d produce. He decorated his walls with paintings: flowers to symbolise peace and two hearts representing himself and his long-lost love, Joyce the barmaid. He called the site Mia Sacra Collina – My Sacred Hill – and it was always kept immaculately clean.

In 1935 Valerio fell 2m off a boulder while working one night and broke his leg. After calling for help most of the next day, he was discovered and taken into Griffith where he was attended by a doctor. Always quiet and shy, Valerio had been exploited during his drifting days and this act of kindness greatly humbled him. Once, in an Adelaide brothel, he’d had a year’s worth of wages stolen from his trousers. On drawing attention to the theft, he was ejected from the premises, but, adding insult to injury, was jailed for throwing a rock through the window of the establishment.

On another occasion, in Melbourne, he was conned out of several months pay by four ‘mates’ who promptly skipped town. Desperately needing cash, he was forced to pawn his only remaining possession of value, a leather overcoat. But he was deceived again, this time by a stranger who took the coat and promised to return with money but didn’t.

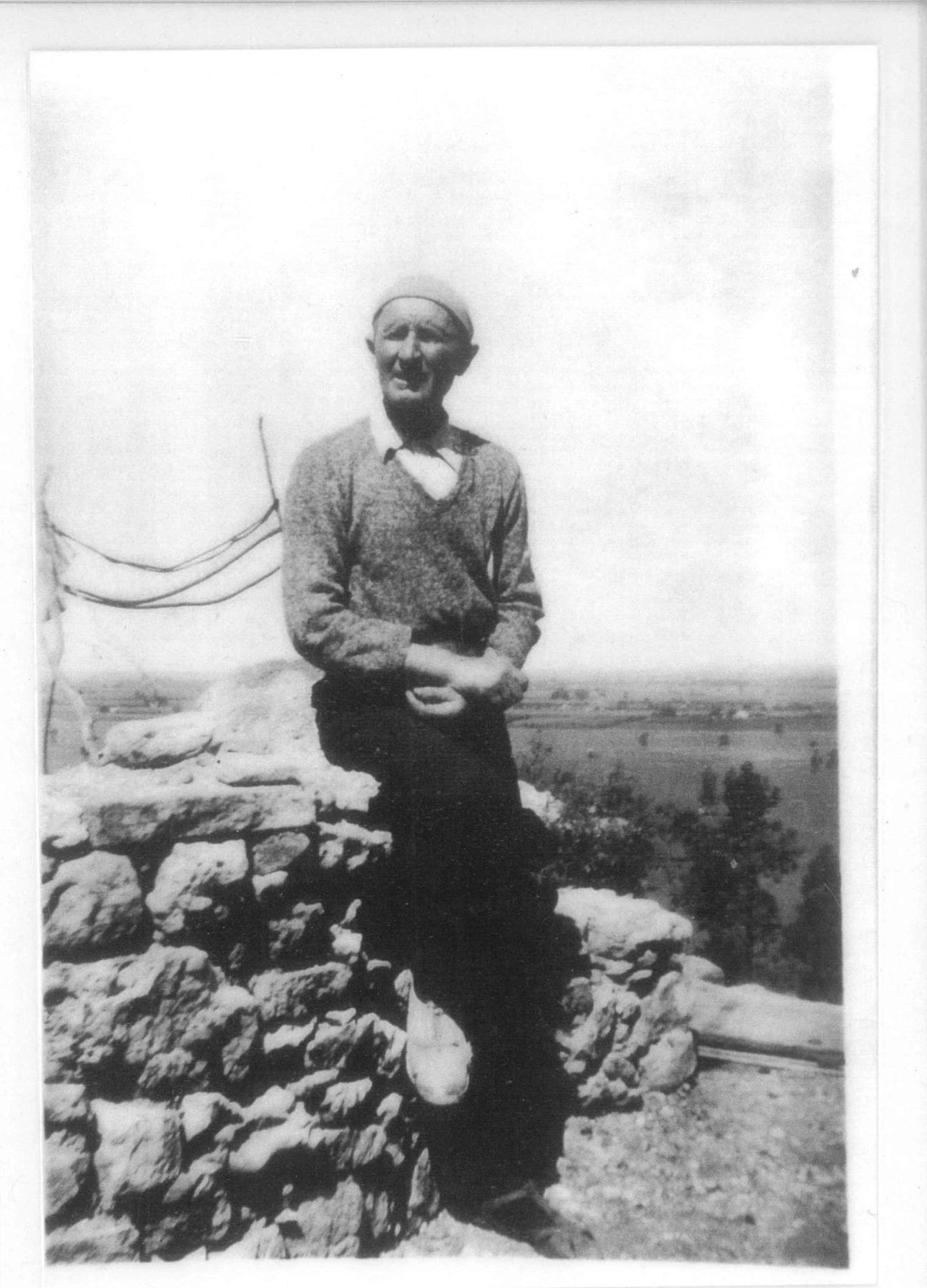

After the visit to the doctor, Valerio’s existence became more widely known, and during the next couple of years, the site received plenty of visitors. Valerio became more accustomed to meeting people, and could sometimes be found tending his gardens, happy to chat or pose for photographs. At other times he’d vanish for days.

Because Griffith’s population was still mostly Italian, it was inevitable his nationality would one day be recognised. Eventually this news reached the ears of Valentino Ceccato, who coincidentally had been Valerio’s landlord in Broken Hill 20 years previously. Valentino determined to seek out this mysterious Italian hermit, and after several months of night-time raids, caught him, whereupon they recognised each other and embraced.

Valentino encouraged his old friend out of seclusion. And although Valerio continued living in the cave, he became more sociable, occasionally visiting town and not hiding whenever visitors came.

Valentino gave Valerio work picking peas on his farm, and helped him buy supplies with his first wages – sugar, soap, matches, tea, flour to make damper and a new suit to wear on Sundays.

This new period of sociability ended in 1940, when Italy joined World War II and all Italians in Australia were required to register as aliens. Rumours abounded that Valerio was a spy, and even though local police dismissed him as harmless, he was interned in a prisoner-of-war camp.

After five months he was diagnosed as ‘disarranged’ and transferred to a mental institution, from where six months later he was released on condition he find proper accommodation in the town.

Valerio was distressed to leave his Garden of Eden, but for the next 10 years he lived and worked on Valentino’s farm, often visiting his former home on Sundays.

While no longer a recluse, he continued to prefer his own company and wasn’t much interested in conversation. He’d often talk to himself, sometimes replying in a falsetto voice. He admitted seeing visions of people in the sky, specifically a woman in white whom he identified as Joyce. These visions would climax every full moon, leading to Valerio’s diagnosis by the town doctor as a ‘lunatic’.

His physical health also deteriorated and in 1952 he voiced a desire to visit his brother in Italy. Valentino helped him buy a return ticket with his accumulated wages and put him on a boat in Sydney. On arrival at his brother’s in Lombardy, he became ill, and sadly passed away soon after. At 53, Valerio had finally found the ultimate seclusion.

These days Valerio’s Sacred Hill is a tourist attraction that feels like an archaeological site. A maintained walking track winds through the old hermit’s gardens and living spaces, which curious tourists explore, attracted by a colourful booklet and signposted heritage trail created by Griffith City Council.