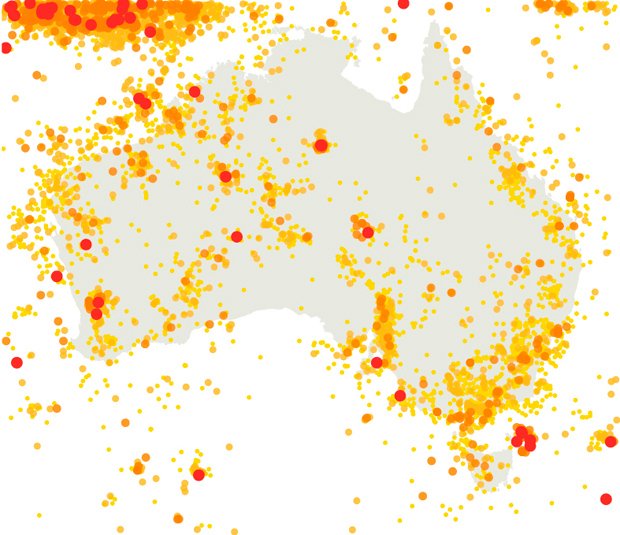

That February 2011 earthquake, which struck during the city’s lunch hour, was the most destructive in a series. It was the one that broke so many of the Central Business District’s verticals and horizontals – its buildings and the roads, sewers, water and gas pipes. It was shallow and ferocious. Its peak vertical ground acceleration of 2.2G (more than twice the acceleration of gravity) momentarily lifted parts of Christchurch to the sort of face-distorting speeds astronauts experience when they ascend into space.

It wasn’t the biggest quake in its series. Five months earlier, there’d been a 7.1-magnitude tremor centred 45km west of Christchurch that damaged the city. But 22 February was different. It was magnitude 6.3, smaller than the previous quake, but the epicentre was just 6km south of the city and even on an international scale it was very violent. Two multi-storey buildings in the CBD pancaked and the low-rise masonry in older parts of the city centre cascaded onto the streets.

The steeple and bell tower of Christ Church Cathedral collapsed into the square, and its whole front face and beautiful rose window – the spiritual and symbolic face of Christchurch itself – teetered, and would later collapse onto the entrance portico, opening the nave to wind and weather, and the pigeons of Cathedral Square.

The February quake killed 185 and triggered an immediate state of local emergency that gave top-down control to civil defence. Then emergency legislation in April 2011 changed it to a state of national emergency that shifted top-down control to a Minister for Canterbury Earthquake Recovery, Gerry Brownlee, and appointed a Christchurch Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA).

That absolute control by the minister and his department proved to be right and proper, for as the years went by, the government would spend more than $14 billion of New Zealand taxpayers’ money on the Christchurch recovery and rebuild.

Yet it was the people of the city, not its appointees, who’d laboured by the thousand amid wreckage to help each other in those post-quake days. It was therefore equally right and proper that the emergency legislation of April 2011 didn’t just set up the top-down authority of a minister and his department, but decreed a bottom-up approach. It called for the people of Christchurch to be given 90 days to prepare a draft plan for building their new city.

Three months. It wasn’t long but the population was already primed. The post-quake days watchword was “When a city falls apart, the people come together” and the people had done that. They’d formed neighbourhood teams to knock down each other’s chimneys. They’d hooked electrical feeds over neighbours’ fences, shared toilets and shovelled the product of liquefaction off each other’s doorsteps. Many had a wage subsidy but no job to go to and their kids had no schools to be taken to. They had time on their hands, and they’d bonded into adult groups that sat around drinking and gossiping.

Then came the invitation to “Share an Idea”. The newly social Christchurch population clinked its glasses, took another sip and clocked up the highest level of community response to city planning NZ had ever seen. The submissions were rendered down to 106,000 separate ideas, broken into themes by council planners and organised into a draft plan that was dispatched to the minister. The mythology of that time has it that the people of Christchurch redesigned their city on a visionary flush of alcohol.

CERA took the plan, set down five-year confidentiality agreements for its planners to sign, then closeted itself for a 100-day rewrite. What emerged came to be called the Blueprint and it specifically acknowledged the first plan of the city laid out in 1850 by surveyor Edward Jollie. Across Christchurch’s flat land the 25-year-old Jollie had laid out a uniform, regular street grid loyal to cardinal directions. At its centre was a cruciform square, with the Avon River – now the Otakaro/Avon – left to wind its own eccentric path across it all.

The Blueprint channelled Jollie’s orthogonal spirit. It took the logic of the grid and enhanced it with a conceptual frame that defined straight-line boundaries to the CBD on three sides. The frames defined precincts – each as wide as a city block, and most six city blocks long. To the north lay the arts and culture precinct. The long inner-city residential precinct was east. To the south was the innovation and health precinct. Then, to complete the western precinct on what was otherwise a strictly rectangular template, the Blueprint gave itself over to the Avon’s meanderings and became the precinct for river-sitting, riverside strolling and on-river punting.

The Blueprint also proposed 13 Anchor Projects – new builds that would buttress the separate identities of each frame. There was a large playground, for example, at the end of the residential precinct and a huge indoor pool and sports complex alongside the health precinct. The Avon precinct would feature a 2km riverside walkway from the Christchurch Hospital through to the big playground, with dark basalt terraces en route that stepped down to touch the river. And just upstream of those terraces, curving gently to follow a bend in the river, there’d be the white marble wall of Oi Manawa Canterbury Earth-quake National memorial, with the names of the 185 earthquake dead inscribed.

The frame enclosed the 74ha space of the CBD, and within that space the Blueprint set out various specialist spaces. The locally beloved Ballantynes Department store would anchor a new retail mall. Justice and Emergency Services would be housed close together. There’d be a new library, a new bus exchange, a big space for a new Convention Centre right next to the Avon, and, at the centre as always, Jollie’s Cathedral Square.

It would be a green city, a walking city, a living city, an intimate city, a market city, a city turned to the river, a city with a height limit of seven storeys – aside from those few high-rise buildings that survived the quake.

These were all features of the draft plan, and Hugh Nicholson, the council’s design leader for the draft plan, was pleased with the Blueprint overall. As for many others, once it came before the public, he’d push back against the Convention Centre site. By its nature it was an introverted building that would be better located further out, but they quickly found it was not their place to say so. “The issue is not what was done,” Hugh says now, “but how it was done. It was done to us. So rather than Christchurch people being invited into the rebuild after Share An Idea, they were cut out.”

The damaged Christchurch Town Hall didn’t figure in the CERA blueprint. It was a Brutalist structure of the 1970s, revered as an avant-garde architectural antidote to old Christchurch’s decorative gothic style. Its concert hall had the best acoustics of any performance space in the land. Its big front pillars stood in reflective pools of water right on the riverbank.

In the 2011 quake its subsurface had liquefied as the quake struck, and those front pillars and other foundation columns had sunk at variable rates and twisted the superstructure above.

CERA wanted the Town Hall’s performance functions transferred to two proposed theatres in the Blueprint’s arts and culture precinct. The council came under pressure to demolish the Town Hall and put its $68 million insurance money into those theatres. But at the end of 2012, the council voted to keep it.

It was the first push-back against CERA’s control of the rebuild. The structure was strong enough to survive nuclear attack but not, suggested CERA and the minister, lateral spread, the slow slide of its unstable footings towards the river. “Broken and unusable”, claimed the minister in a June 2013 opinion piece in the Christchurch Press daily newspaper. And the minister, everyone knew, had power to override the council.

Ten years on, Gerard Smyth, filmmaker, sits in the extensively quake-damaged then exquisitely rebuilt Isaac Theatre Royal. When the earthquake first struck, he grabbed his Sony EX3 and walked straight into the debris to film, one hand pressing into place a lens that had broken away from its mount. He filmed his approach to the fallen dome, shattered masonry, unstable pillars and stone angels of the Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, sobbing as he progressed. In the opinion of many, the basilica had been a finer building than the Anglican cathedral, though tucked away in Barbadoes Street, far from the CBD.

Gerard produced the quake documentary When a City Falls. For the 10-year anniversary in 2021, he produced a follow-up documentary – When a City Rises. One of the film’s protagonists, mental health worker Ciaran Fox, divides up the 10-year recovery period so far into three distinct phases – first a heroic period of rescue, then a honeymoon period of participation, but now a period of disillusionment. It’s a big claim to make amid a $14 billion spend, but as CERA folded up its tent in 2016, the New Zealand auditor-general – the gold standard for unbiased government reportage – investigated CERA’s five-year record, and suggested why that might be true.

The auditor-general reported CERA’s satisfactory performance on its initial demolition agenda and on its housing clearances from areas in the Red Zone (the hub of the damage to the CBD). It had not, though, said the auditor-general, liaised well with the local community during the rebuild, remaining too distant. Nor had it managed the anchor projects in its charge with sufficient rigour.

True, the anchor projects had fallen behind. The Margaret Mahy Playground, named after a NZ children’s author, was the only anchor that hit its delivery date. Still, the bus interchange, the Oi Manawa memorial and the Otakaro/Avon River Precinct, though late, engendered such delight that it didn’t seem to matter.

Other delays, though, had an effect on morale. The new sports stadium, originally slated to open in 2017, remains on hold. The Convention Centre’s opening has been put back four years to 2021. The Metro Sports Facility’s opening is deferred by six years to 2022.

The eastern frame’s medium density residential living is paced according to demand – 172 apartments to date, with another 68 under construction with prices ranging from $399,000 for one-bedroom apartments to three-bedroom terrace designs at $1.25 million. Three-quarters of the estimated build – 660 units – still lies ahead. The eastern frame doesn’t impress Gerard. It’s too expensive for families, he says, and its likely buyers, he believes, will be those in their 60s and older and not the young.

“If the city is peopled, it’s successful,” he says. “If you can look down the streets and there’s nobody there, the buildings can be as lovely as you like, but if they’re not being used, the city is a failure. Well, the city’s empty. It’s not working because retail is not what it was. So the question becomes how to get people back into the city.”

At the premiere of his movie, Gerard received a standing ovation. “It’s a home movie for the home crowd,” he said later. “It was done for us. Let’s say it’s half-time now and the government has done all their stuff and it’s gone quiet. What’s the next act? So the film hopefully enlivens us to all consider that we have choices. We still do because there’s lots of empty land, and the choices made will have to be for individual expression. That fine grain, it’s time for that now. Organic growth. Bottom-up growth.”

The mayor of Christchurch, Lianne Dalziel, is a quake veteran. During the Darfield quake of 2010, she jumped out of bed at 4.35am followed by her husband, Rob Davidson, and they were literally tossed downstairs at their two-storey Bexley townhouse, straight into open space where they stood naked under the stars. After the Christchurch quake she walked from a city office to her home and found it awash with liquefaction.

The mayor meets us alongside the Otakaro/Avon River in the bustling Riverside Market, opened in 2019. Short-order kitchens compete for custom here with a range of ethnic menus. Stalls dispense local farm produce, or newly baked bread. There’s a cocktail bar if you’re inclined. Looking down on the happy chaos below is the repurposed clock that once presided over the demolished Christchurch Railway Station; upstairs in the same building the Riverside Kitchen is one of the city’s innovative startups. It offers Masterchef-style cooking stations for hands-on ethnic cooking classes, or bonding cooking sessions for corporate teams.

Lianne sits down in that same kitchen and champions the city’s new experimental sense of self. “It’s the perfect size. The airport company chief executive always refers to it as the

Goldilocks city – not too hot, not too cold, just right. But for me, I’d frame that in terms of Goldilocks innovation – small enough that you can try stuff and if it doesn’t work, then okay, you move on and try something else. But at the same time for whatever does work, the city’s big enough to build to scale.

“It’s now got the facilities that wouldn’t be available to a city our size anywhere else, so that’s been the advantage of central government investment in us rather than the cost of that. It’s got everything and it’s going to be the city of the future rather than a city reflecting so much on the past.”

During the long quake sequence of 2010–12, the city’s urban population fell by more than 20,000 as people moved out. The city only returned in 2017 to its pre-earthquake population of 376,000, a total that’s since increased to about 385,000.

Lianne is pushing for more and is marketing Christchurch as a great place to live for Aucklanders. “If you offered them what they could buy here, and what they could buy in Auckland, there’s just a world of difference – a better quality of life, less travel time, and good schools, and the South Island environment to play in.”

Later, we inspect the Christchurch Town Hall. Christchurch City Council (CCC) won the fight to save it, although it cost $167 million, and it was reopened in February 2019. The refurbished concert hall is once again an acoustic jewel with regular performances by the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra. The mayor stands in the big resonant space that was saved and you can sense her pride.

Out in the old Red Zone, to the east of the city, Diana Madgin stands at the site of her demolished house. Within the strangeness of the zone, her garden is as neat and manicured as it always was. She saw to that herself, for years, and now pays others to keep it. The cherry tree planted to celebrate her 10th wedding anniversary still holds central place in the garden and, like so much else around here, a central place in her memory.

The Otakaro/Avon flows past what was once her front door en route to the sea. The eastern suburbs of Richmond, Bexley and Dallington all flourished along this river corridor before the 2011 quake. The liquefaction sand beneath these suburbs is weight-bearing when it’s stable, but any earthquake acts like a giant pump. The river corridor sank during the 2011 earthquake by about a metre, and the silt burst through and ruined, or put at risk, 6000 homes.

CERA’s response was to Red Zone wide swathes of land on both sides of the river, buy out the homeowners and demolish their houses. That left an apocalyptic landscape serviced by damp roads to nowhere with leaning lampposts and cul-de-sacs of silted neglect. The sections they served are still populated by backyard fruit trees and delineated by border hedges, but the houses and people have gone.

Diana Madgin was a gardening columnist. Her staple weekly column was a “caulis and cabbage” affair, discussing what vegetable suited what season, but after the quakes she wrote about what supplements and growing techniques suited what types of soil – the differences perhaps between the alluvial soils of this eastern delta and the clay of the Port Hills – because people were shifting around en masse and wanted to know. Then she started to write about trees, and what they meant for the people who’d had to leave them behind. The fruit trees that marked the seasons, the trees planted to mark an anniversary, or to mark a buried pet, or the trees that guarded the ashes of a cremation.

“It was all written on the garden page – a whole collection of those memories,” Diana says. “People would say I can’t bear to leave this because Dad’s ashes are under the trees in the corner of the garden, or under the beech tree by the river. And they’d express their feelings, and why they felt like that. In a way it helps you to know, and it also helps you to leave, because the more you know, the more you can carry away with you. Not that it’s easier to leave but you need to be better informed because leaving is also an act of courage.”

The Crown (the national government) spent more than $1.5 billion acquiring 8000 properties in the various Red Zones of Christchurch. In 2019, when the government negotiated its final global agreement with Christchurch as part of handing all rebuild control back to the city, it sold this 640ha of river corridor to the council for $1. Volunteer groups use it now for community gardens. Those who know the location of the fruit trees use it for foraging. Fitness trails have emerged and plans exist for further recreational development, but fundamentally it’s being given over to flood control, protecting another 20,000 suburban houses on its borders.

The 2011 quake was unusually violent. The filmmaker who embodies a city’s determination to retain its spirit, the mayor who embodies the city’s political will and the gardener who embodies a love of place are characters arisen from a city’s extraordinary travail. And all are pleased, after a year-long vacillation between retaining or demolishing Christ Church Cathedral, that restoration is at last underway.

Cranes pick away at it and engineers figure how to quake-proof without compromising the heritage. A restored cathedral seems likely to be the final capstone of the recovery, but it’s still many years off, and perhaps the man who most closely embodies the reality of it all is Hugh Nicholson.

“With any major city in the world if you do one major work in 10 years you’re doing okay. Big projects take a long time and we were trying to do 10 of them, probably more when you take into account all the repairs at the same time. It was madness.

“Occasionally I get to show people around and suddenly I see gaps and think, ‘My God, they’ll think we’ve been doing nothing. But remember maybe 80 per cent of the CBD came down. It was huge, and I’m really proud of what we’ve done.”