Scientists found a stone wedged in a tree. This is what it tells us about the resilience of Aboriginal culture

A RECENT DISCOVERY on Wiradjuri country in New South Wales shows some of these “culturally modified trees” may be much younger than anybody thought.

What are culturally modified trees?

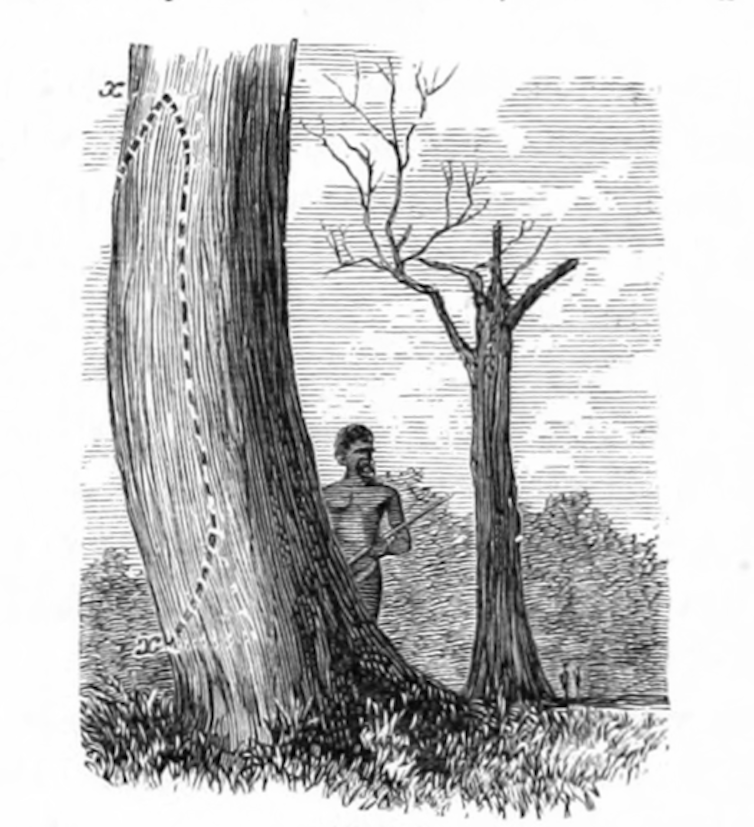

Aboriginal people have long used bark, wood and trees for practical and symbolic purposes. These include making canoes, containers, shields and wooden implements, accessing food resources, and marking ceremonial and burial locations.

Many of these trees contain scars and carvings from these activities, although over time the marks are often enveloped by new growth. Aboriginal culturally modified trees can be found across Australia – you may have walked past one on your way to the footy in Melbourne, on a stroll near Sydney, or somewhere else, without even realising it.

However, their numbers are dwindling as a result of development pressures, bushfires and natural decay.

An unprecedented discovery

One such tree with unique characteristics was recently found on Wiradjuri Country in NSW. The tree has a large scar, and an Aboriginal stone tool is still lodged in the scar regrowth.

Working with the Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council, we carried out an archaeological study of the tree. It represents an unprecedented find in Australia – and even worldwide.

We know that Aboriginal people used a range of stone tools to remove bark and wood from trees. However, no examples of these tools have ever been found lodged in a tree.

We used a range of scientific techniques, including 3D modelling, microscopic analysis and radiocarbon dating, to learn more about the origins of the scar and stone tool. We were particularly interested in how the scar was created, what the stone tool was used for, and when it became lodged in the tree.

Oral history is another key source of information about Australia’s Aboriginal past. However, in this instance, the Orange Aboriginal community does not have any recollections about the tree.

Studying the scar

We created three separate 3D models of the tree, the scar and the stone tool, which show the features of this site.

The scar bears some resemblance to natural scars that can result from fire damage and tree stress. However, the size and location of the scar is also consistent with the way Aboriginal people removed bark slabs to construct shelters.

The stone tool itself provides more clues. The residues and wear patterns we identified on the edges of the stone tool indicate it was made using Aboriginal stone-knapping techniques, and then used in a scraping motion or hammered into the tree, perhaps with a wooden mallet.

Some of the damage we observed on the stone tool may also be from attempts to wedge out bark, or to remove the tool itself from the tree. It is also possible someone used the stone tool to make a visible mark or sign on the tree.

Younger than expected

We used radiocarbon dating to determine the age of the tree, and discovered it was relatively young. It began growing around the start of the 20th century and died about 100 years later, during the millennium drought.

The stone tool was embedded some time between 1950 and 1973 – an unexpected result for the Aboriginal community.

Some members of the Orange Aboriginal community consider the tree, and the placement of the stone tool, to be much older than the dating results indicate. For other members of the Aboriginal community, the dating results are particularly significant as they indicate Wiradjuri culture continued even during active discouragement and assimilation policies.

Historical and oral evidence suggests that Wiradjuri people were, at best, wary about open displays of culture at this time. This impacted the passing of information onto younger generations. The results of our study therefore provide a rare glimpse of cultural continuity at the time.

Although the tree is very large, and therefore appears to be very old, our results also show how rapidly eucalypts can grow. This suggests that many large eucalypts, previously estimated to be hundreds of years old, may in fact be much younger.

The mystery remains

A final mystery is why the stone tool was left in the tree. If it was used to remove bark from the tree, or to create a mark, why was it not removed?

It is unlikely such a stone tool would be left behind, as it appears relatively unused and stone sources are rare in the area. It may have been left accidentally, or because removal was not possible. Another possibility is the stone tool was deliberately embedded in the tree as a symbolic marker in the landscape.

While this aspect of the tree and stone tool may never be understood fully, the results of our study are a clear-cut reminder of the continuity and resilience of Aboriginal knowledge and culture through the 20th century and into the present.

This article was written with the help of the Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council.![]()

Caroline Spry, Honorary Associate, PhD, La Trobe University; Brian J Armstrong, Postdoctoral fellow, University of Johannesburg; Elspeth Hayes, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Wollongong; John Allan Webb, Associate professor, La Trobe University; Kathryn Allen, Academic, Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, University of Melbourne; Lisa Paton, Researcher, University of New England; Quan Hua, Principal Research Scientist, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, and Richard Fullagar, Hon Professorial Research Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.