Meet Ilma Stone, who studied Australian moss for almost 60 years

MUCH OF WHAT we know about Australian mosses comes from the remarkable work of a diminutive, curly-haired Melbournite born in 1913, named Ilma Stone.

Because of the 70 scientific papers she published, we can now explore the tropical mosses of North Queensland through to those of the arid regions of Australia.

Mosses – seemingly unexceptional components of ecosystems – are, in truth, among the most beautifully diverse types of plants, not to mention, ecologically important.

They are key environmental indicators, and stories such as the dying “moss forests” of Antarctica have been critical to understanding the impact of human-induced global heating on the planet.

Australia’s also home to some of the most bizarre species. Take the genus Tayloria, which grows on decaying animal carcasses; its spores are distributed by flies attracted by a pheromone.

While Indigenous people fully realised and harnessed the potential of Australian moss, using it as a source of water, it took awhile for western science to clue on.

The field of bryology – the study of moss – in Australia was crying out for a dedicated scientist with a sharp eye and a commitment to creating a full and detailed picture of these little-known, flowerless clumps of plant life.

Over the phone from New Zealand, Ilma’s longtime collaborator and fellow bryologist Jessica Beever explained to me how she came to science.

“Ilma was a talented student and could have gone to Cambridge after she received her Master of Science degree from Melbourne University when she was 20 years old,” Jessica said. “Her grandfather offered funds to make this happen. But she decided to marry [she married Alan Stone in 1936] and didn’t pursue botany any further at that stage.

“That was until one day in 1959 when she was ironing her family’s shirts. She had the radio on to distract her and suddenly there was an advertisement for a tutor in chemistry. She mentioned it to Alan, saying ‘if only they were asking for a botany tutor’ and Alan encouraged her to call them up and ask.

“Instantly, the botany department at Melbourne University asked her to return.”

By the time Jessica met Ilma in 1981 at an International Botanical Congress in Sydney, Ilma had published more than 20 scientific papers with titles including ‘Two new species of Archidium from Victoria, Australia ’, ‘Bruchia queenslandica, a new moss from tropical Australia’, ‘Acaulon eremicola, a new moss from the Australian arid zone’ and ‘A remarkable new moss from Queensland, Australia’.

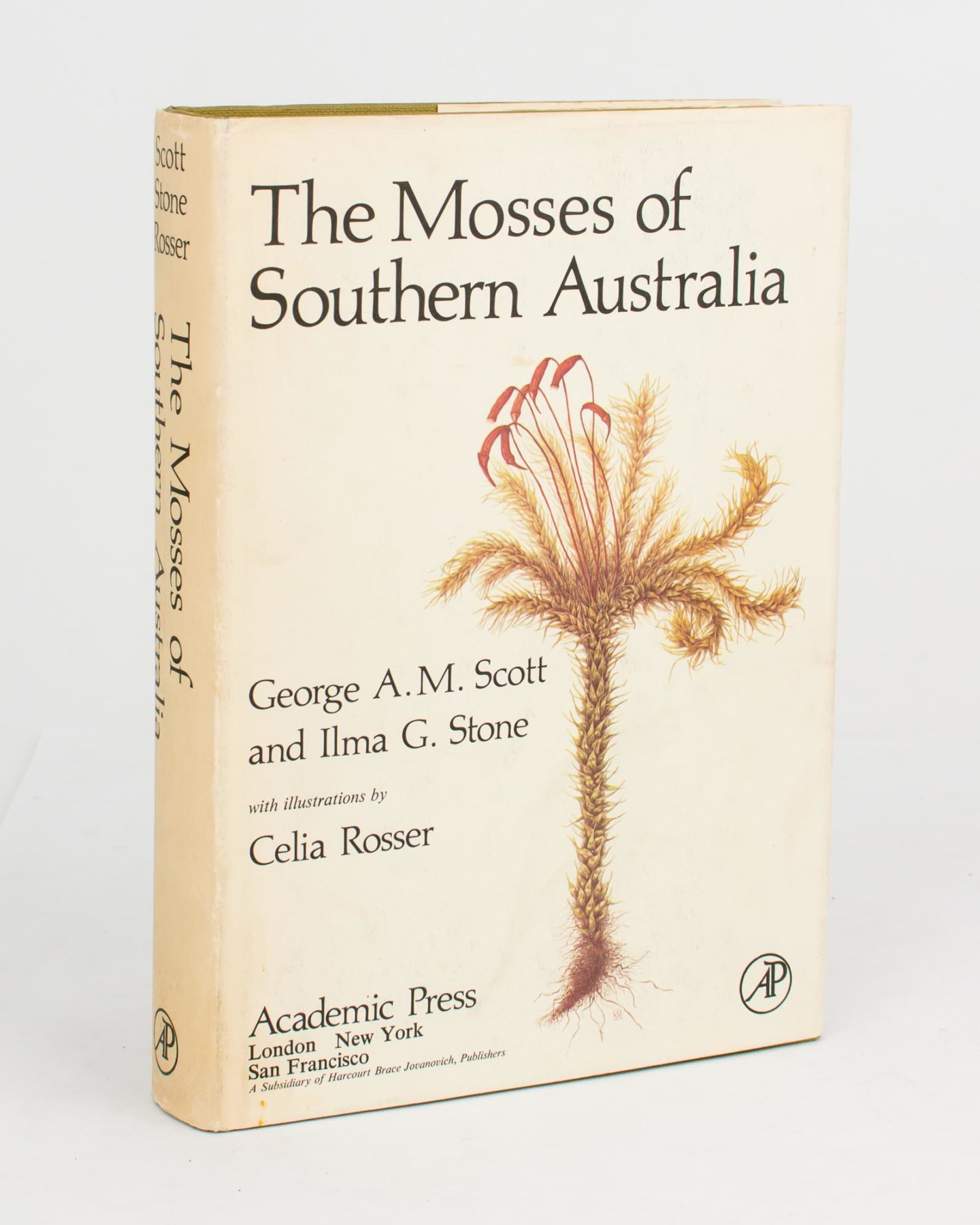

Beyond her scientific papers, Ilma was most well known for The Mosses of Southern Australia (1976), a thoroughly researched book that botanists and bryologists such as Jessica proudly house in their collections. It is now out of print but can be bought on eBay for several hundred dollars.

With its beautiful illustrations by Celia Rosser, it’s one of those rare, collectible books you can only hope that someone has abandoned at a secondhand book store or garage sale, unaware of its worth.

After searching through various academic newsletters and journals, it’s clear countless scientists revere Ilma’s unique skill: her ability to notice almost invisibly small plants.

Having the ability to spot something minute or new in a clump of moss was Ilma’s speciality. “Other people would think ‘ah, too hard, too small’,” said Jessica, but Ilma would pursue.

Indeed, when Ilma wasn’t describing a new species of moss (she discovered more than 25 species; five other new mosses were named in her honour), her papers focused on newly discovered features or the form of particular moss species.

In 1988, Jessica and Ilma began working together, mainly on the genus Fissidens, which is defined by its feather-shaped shoots, and so Jessica came to really appreciate Ilma’s sharp eye and straightforwardness.

“She was gutsy with a streak of seriousness,” Jessica said “She said exactly what she thought, which is good when you’re doing science together.”

Jessica visited Ilma at her home in Melbourne, where she would delicately search through towers of shoe boxes filled with moss specimens – more than 20,000 collected across almost five decades.

By the 1990s, this almost 80-year-old woman had become a legendary scientist.

“When Alan retired from his career as a civil engineer, he said ‘well, you’ve done everything for me, now it’s my turn to look after your career’, and that’s when they made all these trips to Queensland and she was discovering all these new things,” said Jessica.

“Even now, after two cataract operations and hence with considerably impaired vision, she can see enough to be the envy of most other bryologists,” wrote George Scott, who co-authored The Mosses of Southern Australia.

Ilma wasn’t slowing down. “She talked to me about how she couldn’t drive anymore because of her eyesight, but she continued her research because she felt there was so much more to know about mosses and they continued to fascinate her.”

Eventually, however, Ilma began fretting about what would happen to her extensive collection of mosses after her death. Abating her fears, Jessica immediately contacted Pina Milne of the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria.

As with Jessica, Pina had come to admire Ilma through The Mosses of Southern Australia years before meeting her. “I had used this book in my undergraduate years when I completed a project on desiccation tolerance in mosses,” says Pina.

Ilma’s home was a treasure trove for a bryologist like Pina.

“Over a number of weeks I travelled to her house and transported the collection, much of it stored in shoeboxes, from her home to the National Herbarium of Victoria,” Pina says.

“The collection consists of moss specimens collected from the 1960s to 1999, throughout every state and territory of Australia. There were also reprints of her many journal publications, correspondence and drawings.

“It is one of the most extensive and significant contemporary collections of mosses.”

Ilma’s mosses have now been digitised, providing baseline information needed to create plant distribution maps.

“Distribution maps enable the identification of species with restricted ranges and facilitate research on factors controlling distribution, for example providing scientists with a better understanding of possible links between climate and plant distribution,” says Pina.

Sadly, Ilma died in 2001.

“I was sad,” said Jessica. “But I was really pleased that I knew her so well and learnt so much from her. We were lucky to have that time together, and I was even luckier that I got the chance to collaborate with her. It was great to have someone so dedicated and knowledgeable when I was a younger bryologist.”