The only known sculpture of a WWI Indigenous soldier has been found

Germany, 1918. Wünsdorf prisoner-of-war camp, not far from Berlin. An Australian Indigenous POW, Douglas Grant, sits as a model for a portrait bust by a German Jewish sculptor, Rudolf Marcuse.

The completed work is remarkable and of national significance. As Aaron Pegram, senior historian at the Australian War Memorial, recently explained:

“It is the only known sculpture of an Indigenous member of the Australian Imperial Force made during the First World War.”

But the whereabouts of the bust has remained a mystery for decades – until now.

A few tantalising details of the sculpture were on the public record. An entry in The Australian Dictionary of Biography, for instance, states that Grant “became an object of curiosity to German doctors, scientists and anthropologists” and that Marcuse, who was sent to the camp to sculpt portraits of inmates, modelled Grant’s bust “in ebony”. Other biographies have mentioned a bronze or marble bust. But no-one seemed to know where it was – indeed, some questioned whether it existed at all.

After years spent searching European archives and contacting museums and art dealers, we have now found the bust in a small village in rural Wiltshire, England.

It belongs to a retired accountant, Rupert O’Flynn, who keeps it on a plinth in his sitting room and was delighted to hear of its extraordinary history and significance. Cast in bronze (not carved in ebony or marble as conjectured), it is a good likeness of Grant.

A story of art, war, propaganda and race

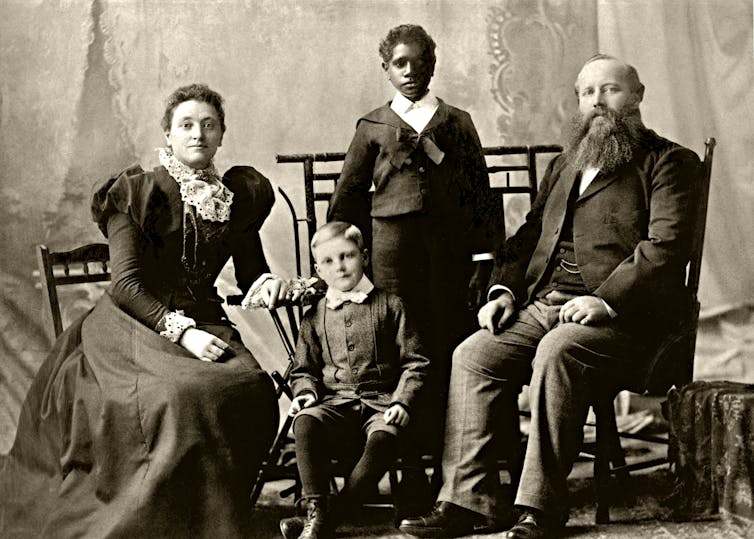

The creation of this sculpture is a story of art, war, propaganda, race, and two individuals forced to flee state violence and oppression. Grant’s life is itself remarkable. Born around 1885 in the Australian Indigenous Nations of the tropical Queensland rainforest, he was “rescued” and adopted in 1887 by a Scottish-born couple, Robert and Elizabeth Grant. They later claimed his parents had been killed in a “tribal disturbance”, a commonly used euphemism for massacre at the time.

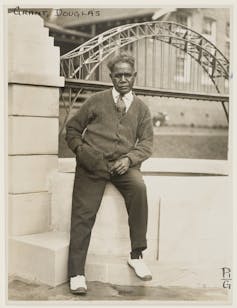

Raised by his adoptive parents in Sydney, Grant trained and worked as a draughtsman before joining the Australian Imperial Force in 1916. He embarked for Europe the same year as a private with the 13th Battalion. In early 1917, he fought alongside around 6000 Australians in the disastrous First Battle of Bullecourt. Half of them were killed, wounded or taken prisoner.

Grant was among the 1,170 Australians captured. As Pegram puts it, they were the largest loss of Australians as prisoners of war in a single action until the Fall of Singapore in 1942.

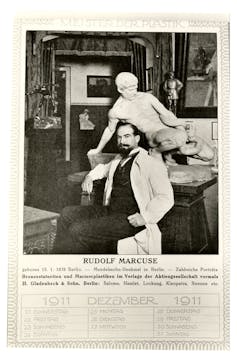

Marcuse, meanwhile, was born in 1878 in Berlin. He studied at the city’s Royal Academy of the Arts and his life-size bronzes and decorative statuettes of public figures were well regarded, with Kaiser Wilhelm II and the King of Siam (now Thailand) among his customers.

When war broke out, the director of Berlin’s National Gallery tasked Marcuse with creating busts and statuettes of the “colourful mixture of peoples amongst our enemies”. The plan was to display them in an Imperial War Museum commemorating Germany’s anticipated victory. Marcuse’s search for “racially genuine types” led him to Wünsdorf, where the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission, an organisation created to record the languages and folk songs of “exotic” POWs, was conducting a scientific experiment.

Only a handful of Indigenous Australians were interned in German POW camps. This made Grant “the prize capture”, according to Roy Kinghorn, an AIF colleague and friend from the Australian Museum. Brought up by white foster parents and with only a bookish knowledge of Aboriginal culture, he was, in fact, a disappointment to the cultural anthropologists. But evidently not to Marcuse.

Sadly, neither man wrote in detail about their meeting, but Marcuse’s lively descriptions of other POWs he sculpted show that he was interested in his models as individuals with unique life stories.

Tracking down the bust

The whereabouts of Marcuse’s bust of Grant had been unknown for decades, until we found a published photograph of it on the website of the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

The museum has digitised large parts of its collections in recent years, including a portfolio of photographs of Marcuse’s busts and statuettes, published in 1919 under the title “Ethnic Types from the World War”. In this context, the bust of Grant was anonymously described as “Australian Aborigine” and sandwiched between a “Siberian” and a “Somali”.

We then tracked the bust from one art and antiques dealer to the next. Finally, we found a British dealer who remembered a “Negro” sculpture similar to the one in our photograph, and the name of the man who had bought it.

O’Flynn had bought the sculpture from the London Olympia Art & Antiques Fair a few years before we met him in 2016. He was thrilled to hear its story. “It has got a presence to it and it is big and bold,” he told us. “It’s just the sort of thing I like and it has a reality to it – it’s fantastic!”

He also mused on the strange journey this sculpture – a German bronze of an Aboriginal man – had taken. “It’s just bizarre for it to end up with me.”

Of national significance

Both Grant and Marcuse struggled to find a niche in later life. Grant returned to Sydney, was a confidant to Henry Lawson, and campaigned for the rights of Indigenous Australians. But it was a prejudiced era and he had difficulty finding permanent work. He spent most of the 1930s in a “hospital for the insane” and died in 1951, aged about 66.

Marcuse fled Nazi Germany for England in 1936. He had applied to join the British war effort as a freelance artist when he died in Middlesex Hospital in 1940, aged 62.

This sculpture is a unique record of their meeting. Given its national importance, we hope that one day it will find its way back to an Australian institution.![]()

Tom Murray, Senior Lecturer and former ARC DECRA Fellow in Screen Media, Macquarie University and Hilary Howes, Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Archaeology & Anthropology, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.