Uluru: Stories in stone

“Has anyone seen Sam?” Sandy Scholz screamed, frantically parting the matted black hair that stuck to her forehead as she ran. In front of her, half a dozen Aboriginal children splashed happily in a waterhole filled by recent, heavy rains. Around them rose the massive, grey sculpture of Uluru, glistening and alive after an early-morning shower. It was a scene that at any other time would have seemed idyllic, magical: a scene little changed for a thousand or more generations.

But for Sandy, it was her worst nightmare. No one had seen her son. Sam, just three weeks short of his fourth birthday, was missing. Not missing at the local show, or in the aisles of Kmart, but missing somewhere at Uluru – somewhere in the middle of Australia.

Sandy had fought back tears as she ran half a kilometre from the bitumen road encircling the Rock to the waterhole. Now, all hope began to evaporate. Sam had clearly not wandered the 2 km from their house at Mutitjulu to the base of the Rock, where they’d been swimming the day before. The repeated visions of her little boy drowned at the bottom of the dark waterhole had been only in her mind. Sam was simply nowhere to be seen.

Sandy tried to think of everything they’d done the day before. It had been one of those extraordinary days – rain beating down onto the darkened faces of a now unfamiliar Rock with all the force of a tropical storm; white waterfalls cascading noisily down scalloped cliffs and narrow gullies – an ephemeral glimpse of the forces that had sculpted this extraordinary landmark for up to 300 million years.

Uluru imprints

Sam had loved watching the frogs and splashing in puddles that filled every depression in the sandy, red-brown soil – something he’d so rarely seen, having grown up near the base of Australia’s most famous natural icon. Usually you’re lucky to see good waterfalls for half an hour just a few times a year. And when it does rain, most of the tourists stay back in their hotel rooms at Yulara, about 20 km away.

It was midday when Sandy had realised Sam wasn’t at home with one of her neighbours. The police were called at 2pm after she’d raced back from the waterhole. Park rangers and some Anangu people arrived just after four.

Immediately and quietly, Daisy Walkabout, Millie Coulthard and Imantura Richards began to look for tracks – a child’s footprints among those of a community of some 200 Anangu and 80 others, including rangers, other staff and families that live and work within Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Not to mention a population of at least that many dogs.

Within 20 minutes, one of the Anangu gave a shout. They’d seen what looked like a partial imprint of a small sandal. Forty metres farther on there was another hint of the footprints of a boy, with two dogs at his side. The tracks were heading almost due south, away from the Rock and into bushland that continues for almost 700 km to the head of the Great Australian Bight.

Anangu tracking

While Sandy sat at home waiting for news, her husband David, six of the local Anangu people and several rangers with food, torches, radios and quad bikes headed south, still not sure they were on the right track. It was a miracle that they could follow any clues at all, for much had been obliterated by a light rain.

Traces of tracks came and went among spiky clumps of spinifex and stands of young desert oak. At one point, the search party stopped atop a dune to pray for Sam: praying he would be kept safe from all the poisonous centipedes and scorpions that’d come out in force with the rains – and from the dingoes.

Gradually, small prints, showing as paler, compressed sand, began to stand out more clearly. As the pace quickened, they reported the story on the ground: “Ngaltatjara. Paluru pakuringanyi.” Poor thing, he’s getting tired here (for his feet were dragging)… He knelt down here to drink from a puddle… He was here when it was getting dark (for his tracks were starting to wander)… The dogs are starting to turn him around now, back towards Uluru. The results of tracking skills developed and passed on over tens of thousands of years were relayed by radio, a 20th-century technology, to a mother waiting anxiously at home.

It was shortly after 1am that February morning in 1997 and after an extraordinary 15km, when the rescuers’ torch beams alighted on a small boy crouched beneath a grevillea bush, two dogs at his side. In the small hours a mother was reunited with her son, safe and well. He’d been missing for more than 14 hours.

In the decade that I’ve lived and worked at Uluru, making films about the region, this was the most extraordinary example of collaboration between Anangu and other Australians that I’ve seen. Forget the buzzwords and slogans such as “reconciliation” or “joint management”; this was “working together” in a most remarkable way.

Uluru – and distant Kata Tjuta – at sunset (Photo: Uluru-Kata Tjuta NP)

Who owns Uluru?

Times sure had changed since my first visit to Uluru in 1981. It’d been a few months earlier that a dingo had crept into a tent – less than a kilometre from where Sandy Scholz was to live – sparking the most famous court case in Australian history and leading to the wrongful conviction of Alice Lynne Chamberlain for the murder of her daughter Azaria.

Back then, the knowledge and evidence of Aboriginal trackers Nipper Winmati and Barbara Tjikatu were readily dismissed in favour of dubious forensic evidence from the Mother Country.

The Anangu regained some of their self-respect – as well as the land that once was theirs alone – on 26 October 1985, with an official ‘Handback‘ of the Rock. Amendments to the Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act and the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act gave the Anangu inalienable freehold title to the park area through the Uluru Kata-Tjuta Land Trust.

RELATED: On this day: Aboriginal Australians get Uluru back

The park was simultaneously leased back to the director of National Parks and Wildlife for 99 years, on the condition it would be jointly managed. The struggle for ownership had its origins in 1872 when explorer William Ernest Giles and his expeditioners saw Kata Tjuta (meaning “many heads” in the Pitjantjatjara language) from across a large, impassable salt lake that he later named Lake Amadeus.

Surveyor William Christie Gosse was the first European to reach the Rock – doing so the following year – and the first to climb it, with his Afghan cameleer, Kamaran, on 20 July 1873. He wrote: “This rock is certainly the most wonderful natural feature I have ever seen.” Gosse named the monolith “Ayers Rock” after Sir Henry Ayers – who would, ironically, remain as the SA colony’s Chief Secretary only until the following day.

When in 1931 Harold Lasseter returned for a last and fatal attempt at finding his gold reef, Aboriginal people were still living traditional lives – collecting maku, or witchetty grubs, from the roots of acacia bushes, grinding the seeds of desert grasses and other plants, and drinking the sweet nectar of bright yellow grevilleas and heath-like thryptomene that bathes the sand-dunes with a honeyed fragrance each winter.

Lasseter’s exploration

Billy-wara remembers Lasseter well. He was perhaps 12 at the time (like most older Anangu, his birthdate is unknown) and Lasseter was the first white person he’d ever seen.

I first met Billy-wara, the most regal of Aboriginal elders, with long white beard and hair, 11 years ago. I recall him stooping his tall, slender frame as he opened the door of the park headquarters, carrying a piti, or traditional wooden bowl, in one hand, a spear (kulata) and spear-thrower (miru) in the other. As he bent forward to put the piti down on top of the photocopier, his 2m spear crashed into the rotating ceiling fan. It seemed an absurdly literal clash of cultures.

With his grandson interpreting, Billy-wara said that seeing Lasseter on a camel 63 years earlier was like seeing a ghost. “I didn’t know what whitefellas were, and then one day we saw this huge beast and on top it seemed like there was a human, but it looked like a ghost ‘cos he looked white. I thought he must be dead.”

Lasseter stayed near the Anangu for some time, shifting camp whenever they did. Billy-wara remembered him getting angry when his camels escaped: “He pulled out this long piece of… To be honest, I didn’t know what it was then, and it made this really loud noise. There was smoke coming out of it, and we started to run away.”

Lasseter was soon dependent upon Anangu as they provided him with all his food and water. “Then one day, Lasseter died. When we found out, we all gathered around and cried and cried,” Billy-wara said.

RELATED: First-ever drone footage of Uluru

The Anangu were soon to become better acquainted with that noisy, long pole. Three years later, Constable Bill MacKinnon – the first European known to have climbed to the top of Kata Tjuta – shot one of Billy-wara’s relatives at the base of the Rock. Years of conflict with doggers, pastoralists and the emerging tourism industry would follow.

The South West Aboriginal Reserve (initially called Petermann Aboriginal Reserve) had been established in 1920 as part of the Great Central Aboriginal Reserve. But in 1958, with pressure from the tourism industry, the 1326 sq. km Ayers Rock-Mount Olga area was excised from the reserve to create a national park.

After the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) in 1976, with the park becoming Uluru (Ayers Rock-Mount Olga) National Park in 1977, the scene was set for one of the most significant days in 20th-century Australia – the Handback, and the beginning of an era of joint management.

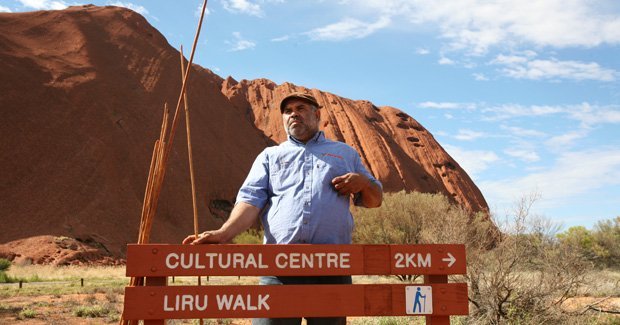

Sammy Wilson, a guide with Anangu Tours, stands near the start of Uluru’s Mala base walk. Shortly before he’d been showing off his spear-throwing skills (photo: John Pickrell).

Return of the mala to Uluru

In preparation for the 20th anniversary of the Handback [in 2005], ranger Jim Clayton was putting the finishing touches on the latest, and perhaps best, example of joint management. With a crew of rangers and Anangu, he was working on the last stretch of a 2 m high fence that would keep cats and foxes out of 170 ha of natural habitat that has become known as the Mala Paddock.

“This was something that Anangu really wanted,” said Jimmy-wara, as he’s known, a broad smile radiating from beneath his broad-brimmed hat. “At the 1999 conference on reintroduction, a group of Anangu ladies and a group of Anangu men were each asked to rank in order of importance to them which animals they’d like to see brought back to the park.”

And so it was that the mala, or rufous hare-wallaby, was chosen for reintroduction to Uluru, obtained from populations reared in similar enclosures elsewhere. It’d been extinct in the wild in Central Australia for decades but was remembered well by the older generation. Mala were central to the Tjukurpa, the Aboriginal law, lore or religion that governs the lives of most Anangu to this day.

There were 46 mammal species known to have occurred here in the 19th century, but now only 25 survive. Other animals and plants have fared better: 416 plant species, 178 birds, 74 reptiles and four frogs have been officially recorded within the park. No doubt, this list is incomplete: wading through a swamp in the heavy rains of 2000, I’d myself come across a fifth species of frog.

Changes to traditional fire regimes may have hastened the demise of some of the region’s mammals; the big fires of 1950 and 1976, which burnt three-quarters of the entire park, would probably not have occurred had traditional techniques of patch burning been in operation. But introductions – rabbits, foxes, cats, camels and buffel grass, to name but a few – have also played a key role.

“We’re still putting mala behind fences, primarily because there’s no effective way to control feral cats at this stage,” Jim said. “When cat control does become available, hopefully, we can open the gates and let them go.

Completion of the mala project

The successful completion of this particular project owes much to Jim’s ability to speak in Pitjantjatjara with senior Anangu (many of whom speak little English) – a skill mastered by relatively few of the non-Aboriginals who work in the park. And after five years as a ranger, he remains realistic and respectful.

“It’s easy being outside this place to forget how different Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cultures are,” says Jim, who’s had his share of waiting around for Anangu to come to work first thing in the morning. “For me joint management is about meaningfully involving Anangu and non-Anangu in the management of this place; the more I work with Anangu I realise, yeah we have a vast amount in common, but the way we approach things is totally different.”

As we drove back from the Mala Paddock towards the Rock, I could see the scene of a rescue I’d witnessed a few years earlier – a narrow, scalloped ravine where one of the rock rescue team abseiled down to collect the pack of a Japanese tourist who’d fallen to his death, apparently chasing his hat.

“I personally would love to see the climb closed,” said Jim, as we discussed one of the most contentious of all park issues. “The most unpleasant part of my job is having to recover people who have passed away, which I have had to do.” That’s probably the main reason why the Anangu today discourage climbing. They feel a deep sense of responsibility for what happens to people on their land and a very personal sadness when someone is injured or dies.

Even with a safety chain on the steepest parts, put up in 1963-64 and extended in 1976, at least 37 people had died up until 2005 as a direct result of climbing. If it weren’t for the chain, few tour operators would allow their customers to risk the one-hour climb to the summit.

The tourism industry, which tends to dominate much decision-making in the national park despite a supposed Anangu majority on the board of management, is generally reluctant to see the climb closed. Yet many visitors say they wouldn’t mind a change in policy. “It’s a funny way to do it,” said Mark Watts, a visitor from the UK whom I met at sunset strip, at the end of a long line of cars. “Telling people they can climb, but that Aboriginals prefer them not to. I think they should just close the climb so people know that before they come here.”

Longitude 131 – an exclusive camping development that forms part of the Yulara resort (Photo: John Pickrell).

Cross-cultural integration at Uluru

Back at the ranger station, social researcher Jasmine Foxlee pulled a large hunk of sandstone from a package and placed it carefully on the scales.

Surrounding her desk were a dozen plastic storage boxes, each full of packages, letters and pieces of the Rock that had been sent here from all corners of the globe. Many more never even make it through Customs; no one volunteers to pay the Customs fee, although in future this fee may be waived.

“It’s an amazing record of cross-cultural interaction – and of the way people are responding to this place,” Jasmine said. “Most people are seeking forgiveness for having taken a rock or some sand from around Uluru when they visited. About 40 per cent of people apologise in writing.

“Surprisingly, only about 14 per cent of the letters I’ve been through talk about bad luck,” Jasmine continued. She read from one of the letters she’s been analysing as part of her PhD on the subject: “I’ve lost my purse and the dishwasher has broken down. Hoping this will correct any harm I’ve done.”

One of the earliest rocks to have been returned was picked up in 1963, a time when fewer than 10,000 visitors came to the park each year. Visitor numbers peaked at 394,000 in 2001, having more than doubled in the previous 12 years, and are set to exceed 400,000 this year [2005].

Uluru’s resort

In Longitude 131, an exclusive mini-resort set a few dunes away from the main resort, it’s hard to relate to the lives of the early European pioneers and explorers whose pictures and artefacts adorn each of the 15 luxury tents. At $3600 for two nights, it’s certainly not the cheapest accommodation in town but, with uninterrupted views to the Rock and uninterrupted service, it’s expecting to have its tents occupied for more than 80 per cent of the coming year.

Four further hotels, apartments and two camping grounds mean that Yulara can now cater for 4500 guests a night which, along with 1100 workers and residents, makes it, when full, the Territory’s fifth-largest settlement.

Fifteen kilometres away from the resorts at Yulara sits the Mutitjulu community, the home of Barbara Tjikatu and other traditional owners of the park. Sitting on the loose, orange sand outside her grey brick house, surrounded by dogs and wood shavings from the artefacts she was making to sell at the cultural centre, we could see across the entire community – to the old garage, where youngsters with few prospects scale corrugated-iron fences to fill Coke bottles with petrol, the cheapest drug in town.

“I want my children and grandchildren to stay in the community,” Barbara told me in her native Pitjantjatjara, as usual throwing in a few words in English to try to help me out, “but there’s no work for them here.”

Beyond the garage is the health clinic run by Bob Randall who’d been taken from his mother when he was a small boy by the same Constable MacKinnon who’d shot a member of the Uluru family at the Rock back in 1934. Behind the clinic is the small primary school where many of the children wear hearing aids, the result of inadequately treated ear infections. “It’s not the stolen generation,” said teacher Michael Ellis, “but the neglected and abused generation. And that’s worse.”

Australian stories of Uluru-Kata Tjuta

And so on 26 October this year we celebrate the Handback of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park to Aboriginal people – at the end of a year in which the Governor-General visited Uluru for Australia Day, hoping to create a new and inclusive meaning for Australia’s National Day. A hope that 26 January would one day be celebrated not just with $9.95 specials for a flag, a meat pie and a can of VB, but with symbols of Australia’s diversity and the incredible antiquity of its own unique cultures – symbols like Uluru itself.

Inscribed on the World Heritage List for its natural values in 1987, and as a cultural landscape in 1994, Uluru has come to be a symbol of Australia in so many ways: the vastness and ancient beauty of our land; the uniqueness of our Aboriginal cultures; and the problems of black and white Australia.

It reassures us that here, at the start of the 21st century, ancient cultures and languages are still alive. The Governor-General couldn’t have known how hard it was to find a dozen Anangu to dance a welcome that warm January morning. Most of the community were away in the western desert region participating in their own, private ceremonies – inma that have changed little for thousands of years.

While we struggle to understand the lives, and will never know the languages of those who painted extinct animals on the walls of European caves some 10,000 years ago, Australia has living ceremonies and songs as ancient as those and older still, with verses that tell of our history, of morality, of law, of creation, and which are literally set in stone.

Etched into the very surface of our national icon are features that tell not just of the tortured geology that has created this unique sculpture and of the unfathomable time since the Rock’s origins, but also preserve some of the world’s oldest memories. Those stories and songs are ours. If we want them to be.

[Editor’s Note: This story was first published in the Australian Geographic journal in 2005 to mark the 20th anniversary of the Uluru handback and the dates in the text have not been altered].