Taking to the Eyre

It’s boom time at the tiny outback settlement of William Creek along the dusty Oodnadatta Track in South Australia as news of a once-in-a-decade flooding event at nearby Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre radiates outwards like the effects of a pebble tossed into its turbid, briny waters.

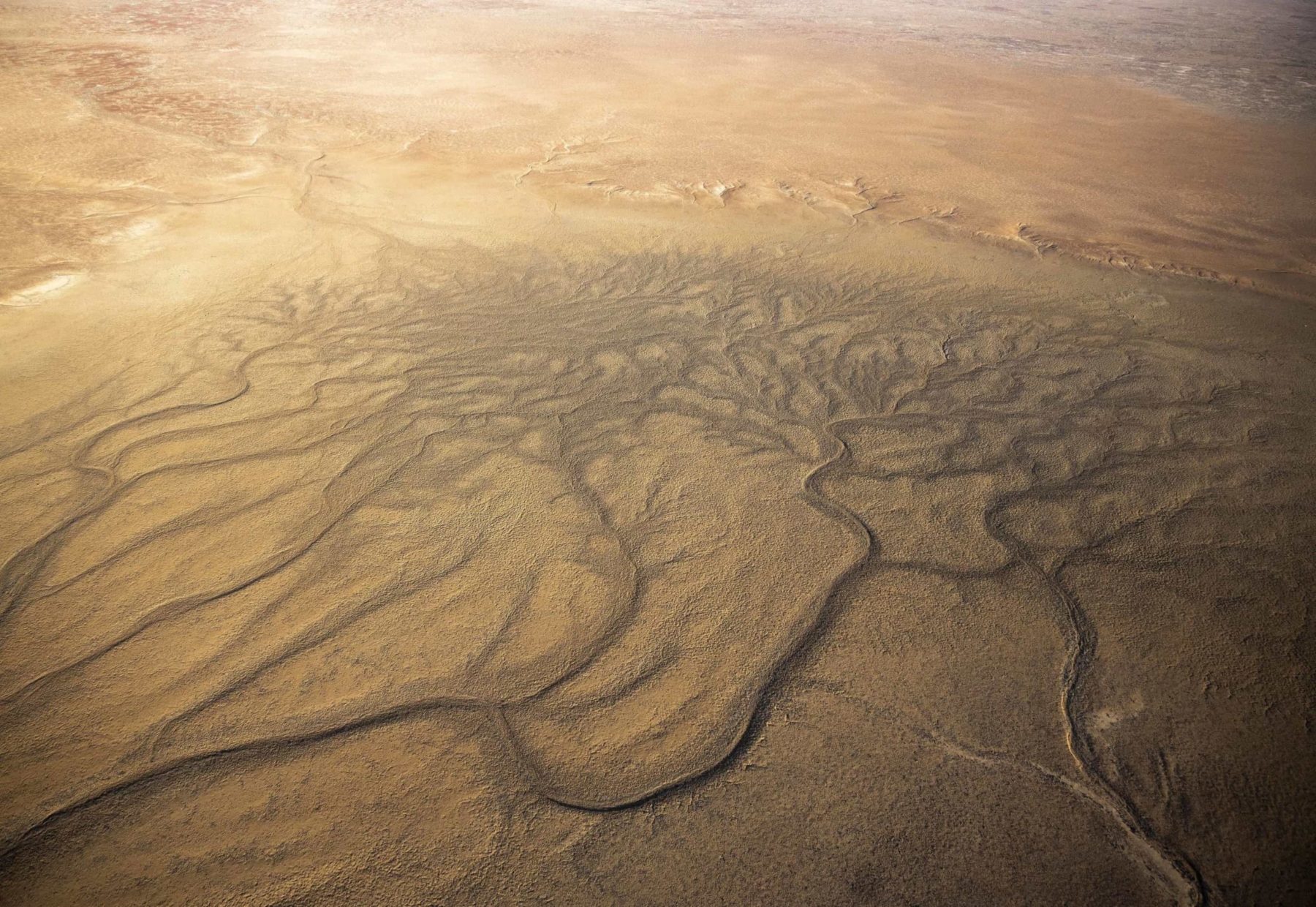

It’s a sunny but chilly Friday afternoon in early May and William Creek’s quirky hotel has been inundated with enquiries following an ABC TV news item the night before. Footage of water surging down through Queensland’s braided inland river channels, turning the red desert green in its wake before emptying into the vast dry lake bed, has pitched William Creek into the global spotlight.

Trevor Wright, proprietor of the William Creek Hotel, woke this morning to more than 200 emails in his inbox, which sent him and his staff into a flurry of activity to meet the sudden demand.

As well as running the hotel, campsite and bar, Trevor, a well-known outback identity, is an experienced bush pilot who runs his own charter airline, Wrightsair. It’s based here at William Creek, which is reputed to be the busiest outback airstrip in Australia.

I’ve been invited by Canon on a guided photography weekend organised under their Canon Collective program, which teams dedicated amateurs with talented professionals in inspiring locations.

During the next two days we’ll make good use of Trevor’s airstrip and his team of expert young pilots as we explore this locality from the air.

My seven fellow participants and I and our two tutors can’t believe our luck. We’ve come here to learn to take aerial photos, so the flooding event at the lake is an unexpected bonus.

We have the use of a couple of eight-seater fixed-wing aircraft, GippsAero GA8 Airvans. Affectionately nicknamed flying bricks, each has a large sliding door that can be pulled back during flight for an uninterrupted view of the landscape below.

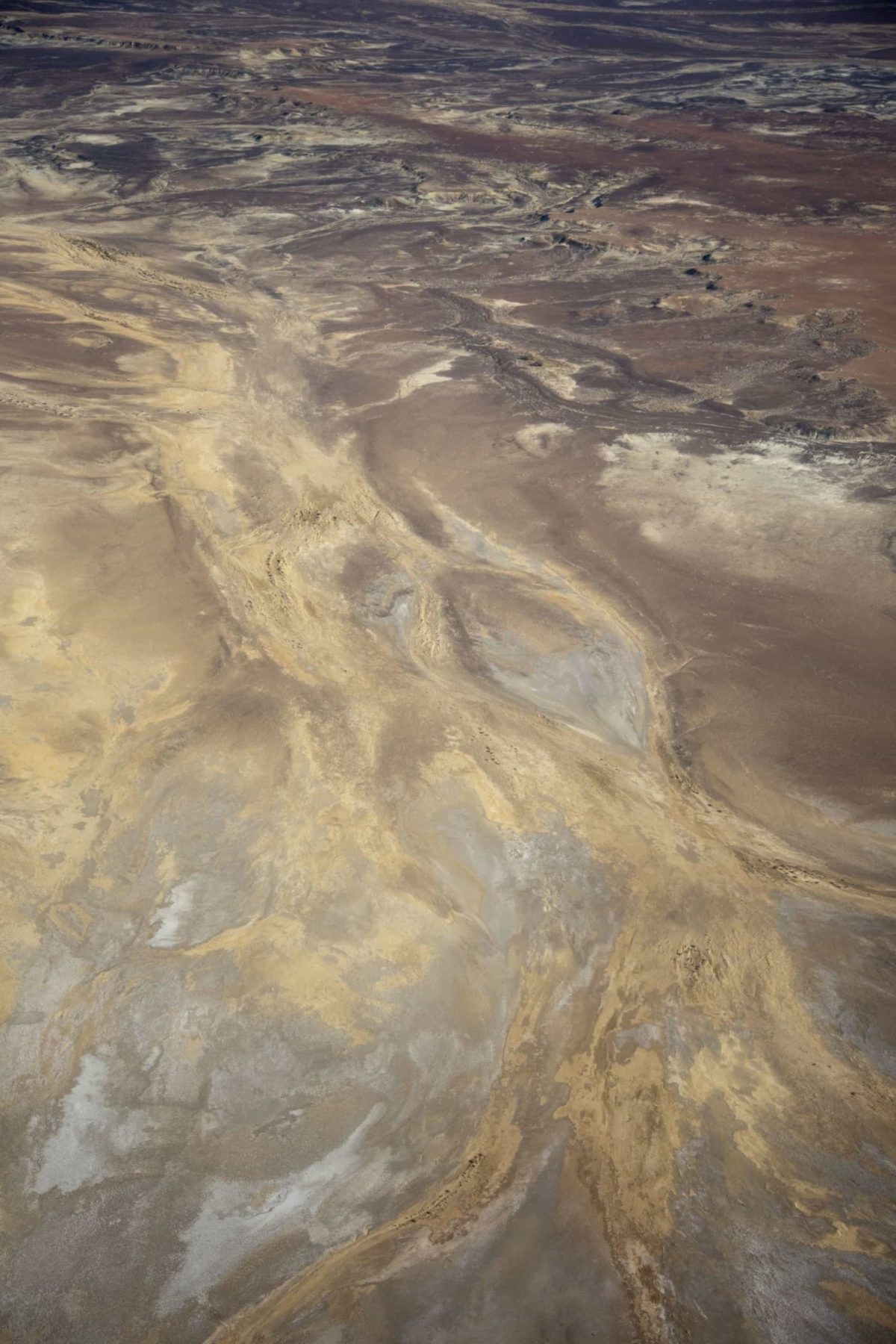

Everyone’s excited about the photographic possibilities offered by the rising waters, but on the first day we fly off in the opposite direction, to photograph a recently discovered geological marvel – the Painted Hills – in the late afternoon light. The strange, Martian-looking landscape, daubed with strokes of ochre, yellow and red from minerals leaching from the rocks, rises up from the otherwise flat gibber- and claypan-studded plain on the vast Anna Creek cattle station. It’s not accessible to the general public by road but it’s possible to fly in from William Creek and land on a recently constructed airstrip to explore the area on foot, or simply enjoy from a scenic flight.

Canon tutor Steve Huddy has advised us on the camera settings best suited to a low-altitude flightpath over the fast-moving scene in rapidly changing light. We reset our cameras accordingly before strapping in for take-off. During the flight we take turns rotating around the aircraft to sit in the hot seat next to the open door for an unimpeded view of the drama.

Everyone here is a dyed-in-the-wool Canon devotee, me included. Today I’ve agreed to try out a new Canon camera system but I’m a little nervous. I know my way around my trusty old DSLR kit with my eyes shut. But this new camera is foreign to me and I can’t afford to miss any shots. I give it a go but keep my usual camera within easy reach.

The sky’s the limit

We land for a terrestrial walking tutorial among the hills and valleys before taking to the skies once more to make the best of the approaching sunset.

As the light turns gold, the multi-hued hills ignite and the colours intensify to everyone’s breathless delight. The photographers’ silent concentration is palpable now, broken only by the hum of engines and whirr of camera shutters in overdrive. Before long it’s dark and we’re back at William Creek for the night. Everyone heads away to their cabins to begin downloading and checking the day’s images before dinner in the bustling restaurant of the William Creek Hotel.

We’re up and out next day before the Sun for the pre-dawn light over Lake Eyre. As our aircraft climbs above William Creek, the only other thing on the move is a giant road train barrelling down the Oodnadatta Track, sending up a rust-red dust cloud in its wake. A thin white band appears on the horizon broadening with every kilometre until it turns into the salt-encrusted shore of Lake Eyre North. The pilot descends to 500 feet, the door is tugged open, with some effort, and the shooting begins. As the Sun appears, it illuminates seemingly limitless waters.

The vastness of the scene is hard to capture in a single frame but the ever-cheerful Steve Huddy offers encouragement as we rotate around the aircraft to take up the coveted shooting position at the door. The low angle of the early sunlight throws the crystallised salt formations along the shoreline into sharp relief and it’s these intriguing abstract sculptures on which Steve recommends we focus our lenses.

When not shooting through the door, I’m experimenting with the new mirrorless model. It’s lighter than my Canon EOS 5D Mark III so I’m starting to see the benefits, but I’m certainly not game to rely on it solely just yet. We explore the far reaches of the lake for a couple of hours, flying in low along the Warburton Groove, where the fast-flowing floodwaters from the north funnel down a narrow channel before emptying into the lake proper.

By late morning we’re back at camp and gather together to share the morning’s images and learn a few image processing tips and tricks from Canon professional Jay Collier, and from each other. Everyone seems grateful for the downtime to process photos, charge batteries, eat, and explore the William Creek precinct.

In the afternoon we’re in the air again and this time Trevor Wright is at the controls. Trevor’s a trove of local information and keeps us entertained with his witty anecdotes and stories of his 35 eventful years at William Creek. He knows the lake well and flies us around even more of its jaw-dropping immensity. He explains how the wind can move the entire body of water from one part of the shallow lake bed to another. The putty-coloured water ripples gently in today’s light breeze and the numerous islands and crusty shorelines provide interest, colour and texture for our photos.

Burning the midnight oil

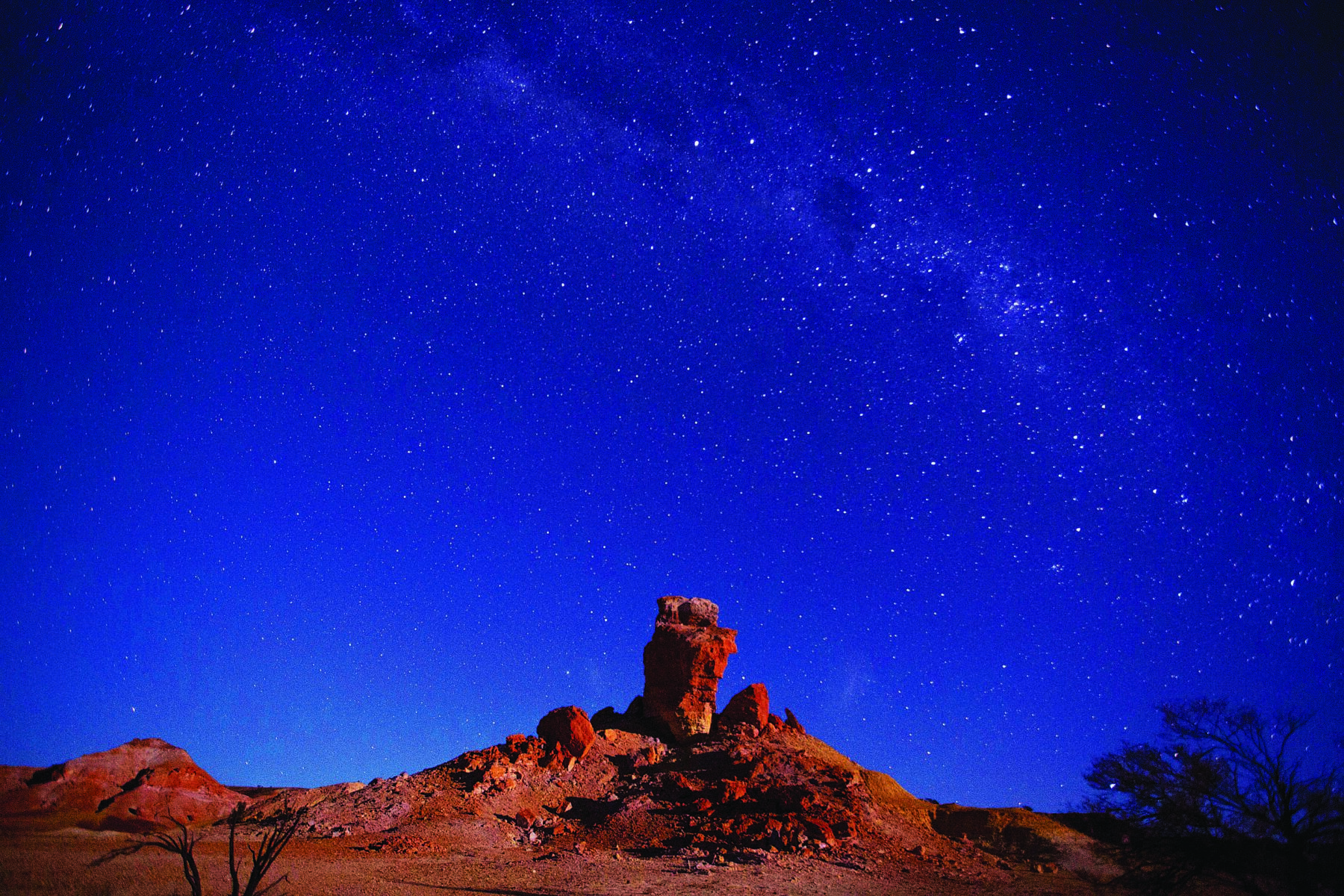

The clear autumn sky above William Creek is perfect for stargazing so later that night when the Moon’s up, Steve and Jay lead us beyond the lights of the little township to a rusty disused former Ghan railway bridge to learn the art of astrophotography. I point my tripod head and camera at the sky and snap away, adhering to the expert instructions, but can see nothing at all on the playback screen in the inky darkness.

The Milky Way, almost invisible to the naked eye in the night sky, looms miraculously out of my photos when I download them the next morning and I’m thrilled to have acquired a new skill.

Our cohort of shutterbugs hail from all corners of Australia and all walks of life. They’re united by a love of photography and the wild places it can take them and they all cherish the opportunity to travel with like-minded souls.

Heather Rose from Vermont in Victoria is a regular at Canon Collective’s one-day workshops in Melbourne with Jay Collier, but it’s her first trip away with the project. “Every time I work with Jay I learn something new,” she says. “He has a knack of figuring out exactly where people are at with their photography. He’s not intrusive and is always able to teach me something new.” Heather is an experienced aerial photographer, but this year Lake Eyre is something special. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see the lake the way it is at the moment. I love the abstract nature of what you can see in there and what others can see in your images of it.”

A bird’s-eye view

Onofrio Deserio from Pascoe Vale in Victoria is a keen birdwatcher and it’s that passion that has brought him to photography. “The natural extension of identifying birds is to record them with a camera,” he says.

There aren’t too many birds to shoot in this arid region of SA so I ask him what drew him to photograph here. “I needed to do more than shoot 2-inch-high birds and I wanted to try my hand at this kind of landscape photography,” he says. “It has been amazing to see Lake Eyre as this great ocean, like an inland sea.” For Onofrio, one of the highlights has been the contrast between the surrounding desiccated desert and the life-giving waters with their promise of new growth.

“It’s so difficult to capture because it’s so large,” he says of photographing the lake. “Even the widest-angle lens has a tighter perspective than the human eye, so I decided not to take photos all the time but to look with my own eyes and take in the abstract shapes and patterns. I hope I have also captured that in my photos.”

We bookend our stay at William Creek with one final flight back over the Painted Hills in the fleeting dawn light. I set up both cameras in the way I’ve been taught and snap furiously away while I’m ‘on the door’. But the rest of the time I decide to follow Onofrio’s example and simply gaze out through the perspex window to try to absorb the beauty and power of a landscape that few will ever get to experience.

It gives me time to reflect on the true magic of photography as a pastime or a profession – of its ability to take us to places off the beaten track and encourage us to really look closely to identify and capture the beauty in any scene and, hopefully, communicate that beauty to others.