Unearthing quolls’ weird, snail-eating cousin

Malleodectids lived in Australia during the Oligo-Miocene. Their fossilised teeth – found at the Riversleigh World Heritage Area in north-western Queensland – indicate these long-extinct carnivorous marsupials were likely specialist snail eaters.

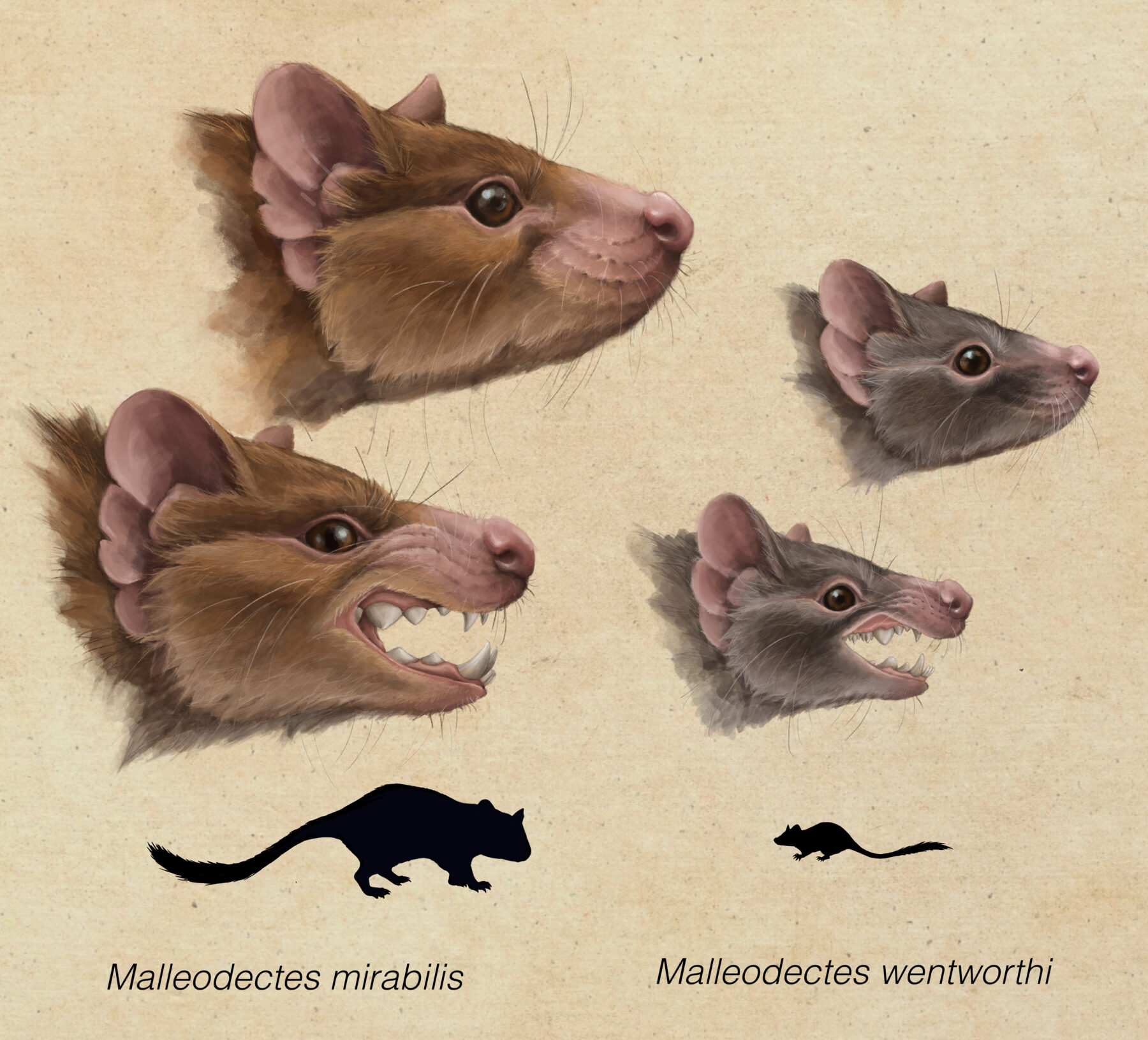

The research, published in Journal of Mammalian Evolution and led by palaeontologist Dr Timothy Churchill at the University of New South Wales, also confirmed that Malleodectes mirabilis and Malleodectes wentworthi are two distinct species of the same genus.

Escargot ecological niche

Dr Churchill said the malleodectids’ molars are typical of generalist carnivorous marsupials today – but it’s their premolars that are “really bizarre”.

“Normally, premolars are narrow, blade-like and smaller than the molars,” he said. “Malleodectids have enlarged enlarged, dome-like premolars, which look kind of like a ball-peen hammer, way bigger than the molars.”

This suggests their premolars were highly specialised for a “hammer-like dietary function”, allowing the marsupials to crack open shelled prey such as snails.

“When we look at other animals in the animal kingdom that have these really strange dome-like teeth, we see a real focus on hard-object eating,” Dr Churchill said. These include the pink-tongued skink (Cyclodomorphus gerrardii), which lives in rainforests on Australia’s east coast, and Caiman lizards (Dracaena sp.) in the Amazon. Both species are specialist snail-eaters.

“We don’t have any hyper-specialised snail-eating mammals in the world at the moment, so they represent a branch of mammalian evolution that seems to not exist anymore,” Dr Churchill said. “But in the fossil record, there seems to be multiple occurrences of it.”

Fossilised snail-eating mammals across the globe include North America’s Didelphodon vorax and other stagodontids, which lived alongside dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous, and a handful of Eocene species found in Brazil and Turkey.

“It seems to be an ecological niche that was very frequently inhabited at certain points of time, but this seems to be not the case anymore,” Dr Churchill said. “So, we don’t know why, but it’s really amazing to have these super-specialised marsupials in Australia that are convergent on otherwise unrelated mammal groups around the world.”

The single known tooth of the newly described Weirdodectes genus is even more puzzling.

“It was definitely eating some sort of hard-bodied invertebrates, but we have no idea what it was eating,” Dr Churchill said. “The only tooth we have from this animal, which is a first lower molar, looks somewhat similar to Malleodectes but has highly reduced blades and closely spaced cusps, which is unlike any other carnivorous marsupial we’ve seen in Australia. Your guess is as good as mine as to what it was and what it was eating.”

A treasure trove of teeth

The fossilised teeth were excavated in the Riversleigh World Heritage Area, a vast area of limestone plateaus containing more than 300 fossil sites spanning the past 26 million years. Dr Churchill described Riversleigh as Australia’s richest mammal-bearing fossil deposit, and added that its reptile, bird, amphibian and invertebrate fossils are just as impressive.

Malleodectids lived during the Oligo-Miocene at a time when outback Queensland, and probably most of Australia, was covered in lush rainforest and earth’s climate was about 2–4°C warmer than it is today. Dr Churchill said this period was a “golden age of mammal evolution” because of its incredible species diversity.

“There were plenty of different carnivorous mammals inhabiting all sorts of ecological niches, and no doubt there are many more awaiting discovery,” Dr Churchill said. “This diversity is way above that for any habitat in Australia today, and more like that found today in the Amazon or Borneo. In all probability, we’re only starting to scratch the surface of the true diversity that is already making Australia internationally famous.”

Many animals, including the malleodectids, met their end at Riversleigh after falling into pools in caves developed in older limestones – kind of natural pit traps. “They either died on impact or slowly died after becoming trapped in those caves,” Dr Churchill said. “The carbonate-rich water encased their bones in crystalline limestone ensuring that even the most delicate of skulls was protected from subsequent destruction.”

Malleodectids went extinct at the end of the Miocene, when the cooling climate dried out landscapes and caused rainforests to contract. Mass extinctions followed.

“What we see in the fossil record after the middle Miocene, and not just for mammals but for all vertebrate groups, is a massive decrease in biodiversity and yet at the same time a large increase in average body size,” Dr Churchill said. “With a greater need to spend more time searching for less nutritious resources, animals – especially mammals – became a lot bigger but also a lot less diverse.”

The fossil assemblages at Riversleigh reflect this diversity loss and provide a cautionary tale about the future.

“It gives us a little bit of an inkling about what may happen when climate changes like this start to happen again – as they are now anticipated to do” Dr Churchill said. “When the climate changed like this during the Miocene, species diversity really, really got hit hard and Riversleigh shows both the start and the end of that golden age, which is a really good reason to do whatever we can to stop this ecosystem crash from happening yet again.”