Who’s the most famous Australian of all time?

That’s the first question I ask my audience on the after-dark tours I host at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) in Canberra. Almost without exception, and with little or no nudging, the same response is inevitably hollered from the bleachers. And, surprisingly for a country obsessed with chasing balls and swimming up and down a black line in a pool, the answer is not a sportsperson.

It’s Ned Kelly.

And that’s my cue to press play on the world’s first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, which first screened in Melbourne on Boxing Day 1906. Shortly after, in early 1907 after watching the film, five children in country Victoria held up a group of schoolchildren at gunpoint. Authorities acted swiftly and banned the film in towns with strong Kelly connections such as Benalla and Wangaratta. Nonetheless, the film was a box-office hit, enthralling viewers for 10 years and further entrenching Kelly’s exploits into our national psyche.

Whether you view him as a cop killer or champion of the downtrodden, Kelly has infiltrated just about every corner of Australian life. You can hardly venture anywhere in our country without being reminded of the bushy-bearded bushranger. The letterbox at the end of my street is bluntly hacked into the shape of his trademark armour, and the overworked barista at my local cafe proudly sports Kelly’s famed, albeit unsubstantiated, last words – ‘Such is life’ – inked on his milk-frothing arm. And I don’t live within cooee of Kelly country.

So, what exactly did Kelly – born in country Victoria to Irish parents, his father a former convict, and just 25 years old at the time of his execution – do to deserve such notoriety?

It’s something a long list of commentators, criminologists and historians have grappled with, none more so than self-confessed Kelly enthusiast Craig Cormick. Craig edited the 2014 tell-all book Ned Kelly Under the Microscope: Solving the forensic mystery of Ned Kelly’s remains, arguably the most comprehensive attempt to separate fact from fiction about Kelly’s life and death.

“Many countries have stories of folk heroes,” Craig explains. “European Australia didn’t really have one until Ned came along, and he fits the mould perfectly – he’s both a folk hero and an antihero all rolled up in one.”

When I prod Kelly devotees during my exposé at the NFSA to divulge what makes him so (in)famous, most surprisingly answer with a question: “Oh, didn’t he take from the rich to give to the poor like Robin Hood?”

“The Robin Hood argument has some merit,” Craig says, “at least for rural poor people near Jerilderie on the Victoria–NSW border area.”

After robbing the town’s bank in 1879, Kelly set fire to mortgage documents and other securities the bank held as collateral for loans, daringly declaring: “The bloody banks are crushing the life’s blood out of the poor, struggling man!”

But Craig is quick to pour more than a trickle of cold water on the Robin Hood comparison. “We easily overlook the darker side of his reality – that Kelly took part in killing three policemen, or that he planned to derail a police train in what today would be termed an act of terrorism,” he says. “Your trajectory in history is determined [by] how it plays out, and Kelly is remembered by many for standing up, against the odds, against the police troopers at his last stand.”

However, the mythology that has elevated Kelly to antihero status extends well beyond comparisons to a fictional character prancing around in green tights and that bold last stand at Glenrowan that spawned the national idiom of bravery: ‘as game as Ned Kelly’.

It’s only when you steal a peek behind his tin mask, interrogate his defiant last words, delve into an alleged curse and probe the reverential treatment of his skull, that the real Ned Kelly unravels.

Helmet power

Can you imagine Ned Kelly without his trademark armour? Or Sidney Nolan’s celebrated series of paintings without Ned in that helmet? Despite its imposing appearance, the armour, crudely crafted from farm ploughs, was much more than a physical defence. It was also a compelling symbol of the Kelly Gang’s defiance and resistance against the established order.

Craig doesn’t underestimate the figurative power of the helmet. “It’s one thing that really sets Ned apart from the other bushrangers. Over time, without physically wearing it, people tend to fill that mask with their own wishes or desires,” he says.

“For example, I was up at a rodeo in north Queensland, and the guy next to me had a big Ned Kelly tattoo on his arm. I spoke to him about Glenrowan and, remarkably, he’d never heard of the place. For this guy, Ned and his mask represented a step away from the mainstream, a streak of antihero and disregard for authority.”

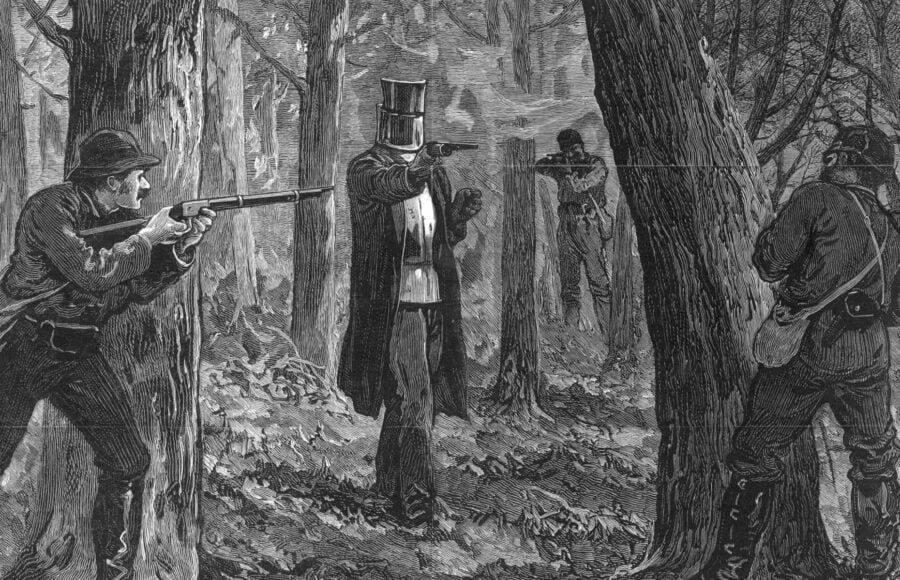

But the armour was also Ned’s Achilles heel. Taking on more than 30 police in the final showdown at Glenrowan while donned in iron plates weighing more than 40kg, and with his lower legs exposed, was always going to end badly. It slowed Kelly down, and although no bullets penetrated his armour, he suffered extensive bruising and lacerations from their impact. He was finally felled by a barrage of lead shot fired at those unprotected legs.

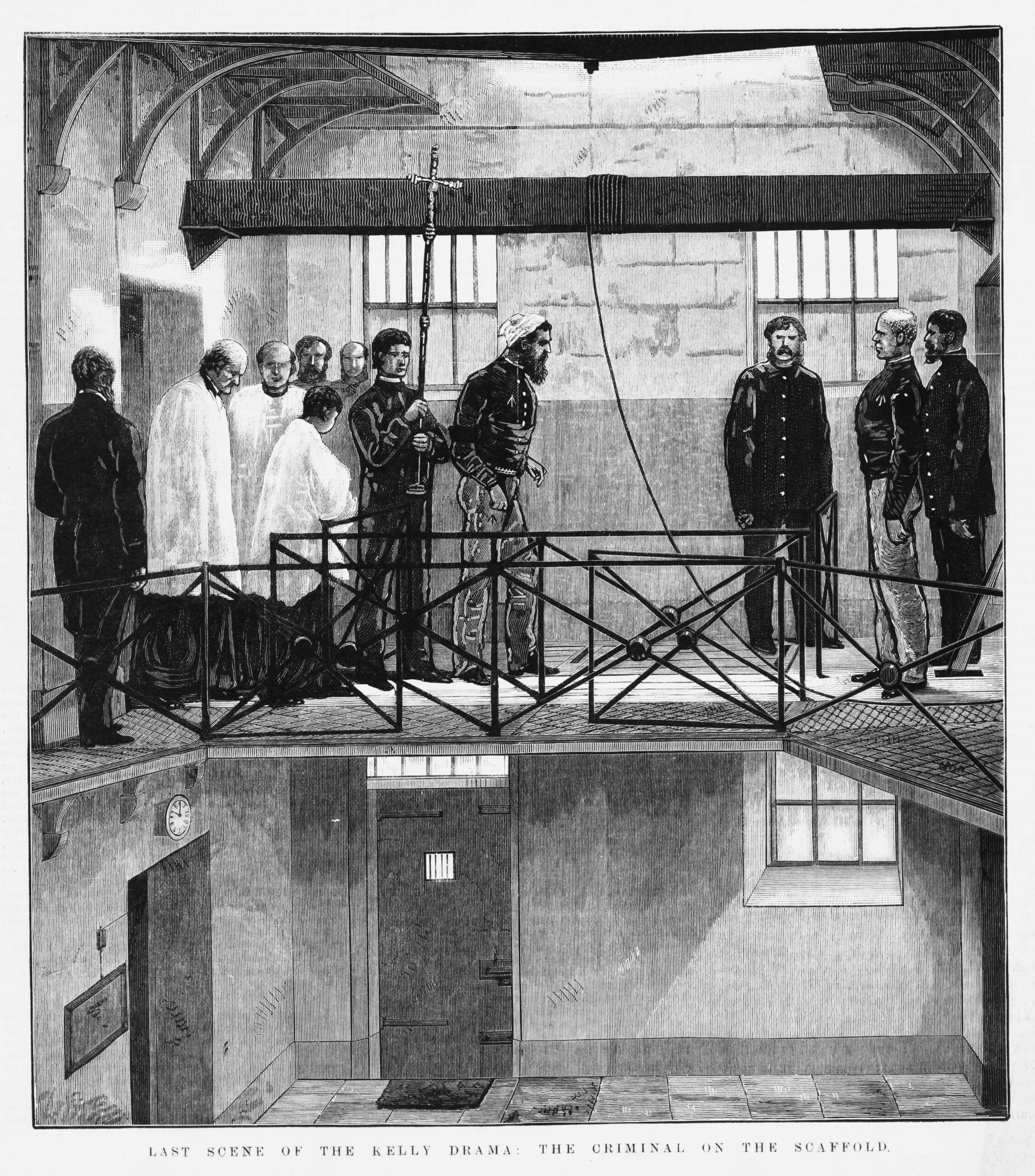

Contrary to popular belief, we can’t be sure of Kelly’s last words as he waited for the hangman to drop the gallows at 10am on 11 November 1880 at (Old) Melbourne Gaol.

The plethora of media reports that followed Kelly’s hanging are conflicting, to say the least. While The Goulburn Herald and Chronicle reported Kelly uttering those three now-famous words, a reporter for The Argus who witnessed the hanging from below the platform reported that Kelly’s last words were, “Ah well, I suppose it has come to this.” A reporter for The Sydney Morning Herald heard something similar: “Ah well! It’s come to this at last!”

Unfortunately, the records of Henry White – the gaol warder who was standing much closer to Kelly than the eager throng of voyeuristic journalists – are unable to shed any light on the conundrum. He apparently scrawled in his diary that, just as the rope was adjusted around Kelly’s neck, the condemned outlaw “opened his mouth and mumbled something [he] couldn’t hear”.

“If different people, including journalists, heard and reported different words, then we seriously need to question whether ‘Such is life’ really were his last words,” Craig says.

After meticulously analysing the reportage of the day, historian Dr Stuart Dawson goes one step further. “The image of Kelly standing tall and defiant, saying ‘Such is life’ as the rope was placed around his neck, is nothing short of a romanticised myth,” he declared in his no-holds-barred paper published in Monash University’s Eras Journal. “It’s pure fiction…in fact, Kelly came to an ignominious, mumbling end on the scaffold, a far cry from popular legend.”

Ouch. That’ll send shivers up the spine of even the most rusted-on Kelly enthusiast.

Poor treatment

If Kelly could come back and haunt anyone, Sir Redmond Barry – the judge who presided over his trial and ultimately sentenced him to death – would be top of his list.

But Kelly held a serious grudge against Barry long before he was marched to the gallows. Twelve years earlier, Barry had condemned Kelly’s uncle, Jim Kelly, to death – later commuted to 15 years in prison – for arson and attempted murder.

In 1878 Barry sentenced Kelly’s mother, Ellen, to three years in prison for the attempted murder of Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick. Kelly always asserted the trooper fabricated the story, and many commentators supported these claims – especially after the disgraced constable was later sacked from the police force for ‘general misconduct’.

Ellen was still serving her sentence at Melbourne Gaol when her son was executed and reportedly heard his execution from within the walls of her cell. And for the record, no, she didn’t hear him say ‘Such is life’.

Just to rub salt in his wounds, it was also Barry who shrewdly moved Kelly’s trial from his home turf at Beechworth to faraway Melbourne because of fears that his sympathisers would interfere with a trial.

Despite the well-publicised animosity between the two men, just after the judge handed down Kelly’s death sentence – followed by that customary legal benediction, ‘May God have mercy on your soul’ – Kelly created an uproar in the courtroom when he responded, “I will go a little further than that. I will see you there where I go.”

In saying this, some believed Kelly was placing a curse on his nemesis. Kelly’s words took on an even more sinister meaning when, less than two weeks after his lifeless body was cut from the scaffold, Barry joined him six feet under. Of course, there’s no scientific basis for a curse, and Barry’s death certificate stated he succumbed to a combination of pneumonia and blood poisoning from an untreated carbuncle – but that hasn’t stopped the so-called curse becoming engrained in Kelly folklore.

On the eve of his execution, Kelly wrote to the governor of the gaol pleading for him “to grant permission for my friends to have my body so they might bury it in consecrated ground”. His request was rejected; after Kelly’s lifeless body was removed from the gallows, his still-warm corpse was openly picked over (that’s putting it nicely) by medical students. He was later buried in the labour yard at Melbourne Gaol alongside dozens of previous prisoners who’d suffered the same fate. But it wouldn’t be his final resting spot. Far from it.

In 1929, when the gaol was decommissioned, the bodies of the executed prisoners, including Kelly’s, were exhumed and reinterred at Pentridge Prison. When word spread that authorities were about to dig up the bones of the notorious bushranger, a crowd gathered. Some were there for much more than a sticky beak, and in the chaos, graves were looted.

Fearing the holy grail of Kelly’s skeleton would be filched, Henry Lee, one of the contractors involved in the exhumation, grabbed the skull for safekeeping. He then kept it on his bedside table (really!) for a couple of nights while he mulled over what to do with it, before eventually handing it over to a state official.

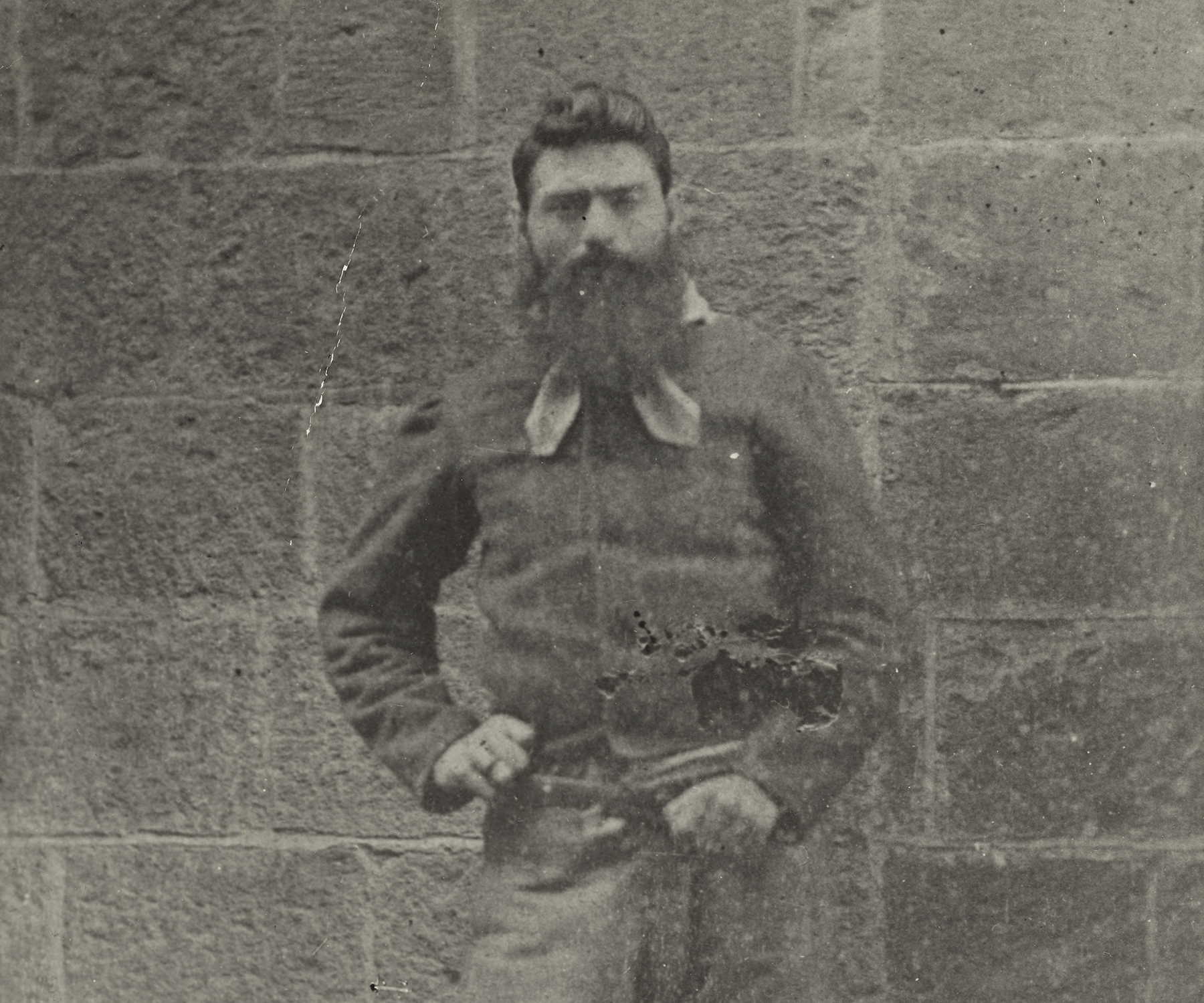

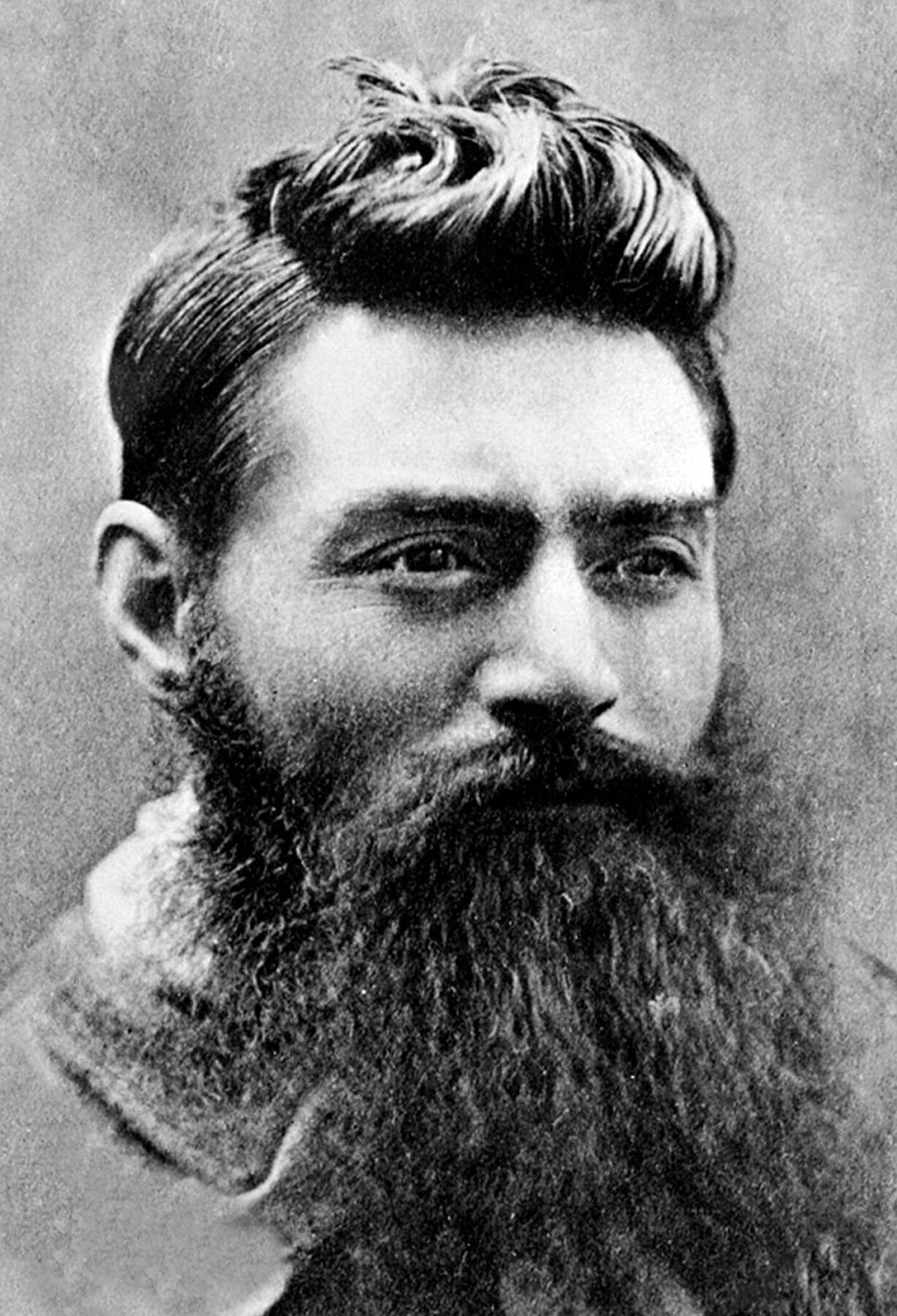

Top: A police photograph taken in 1874; Boxing (date unknown); A police mugshot, aged 15 years old.

Image credits: courtesy State Library Victoria; Historic Collection/Alamy; Historic Collection/Alamy

Bottom: Two portraits taken by photographer Charles Nettleton at Melbourne Gaol on 10 November 1880 – the day before his execution.

Image credits: courtesy State Library of Victoria; Alamy

‘Ned’s Head’

The skull’s whereabouts remained a mystery until the early 1930s, when it reappeared as a prized possession in the collection of prominent Victorian comparative anatomist Colin MacKenzie. MacKenzie was the driving force and first director of the newly created Australian Institute of Anatomy in Canberra – now home to the NFSA, which ironically houses dozens of films about Ned, including the aforementioned world’s first feature film.

Although MacKenzie collected heads for science, he thought visitors – no doubt propelled by a fascination with our brutal colonial past – would be captivated by the national relic in a similar way to pilgrims being drawn to the heads of martyrs in churches in Europe. And he was right; it drew the masses.

However, subsequent directors of the institute saw Kelly more as a convicted criminal than a knight in shining armour and removed the skull from display, consigning it to a box squirrelled away in the bowels of the building. It was only rediscovered again during the clean-out of a basement safe just before Christmas in 1952.

Less than 20 years later, the skull was escorted back to Melbourne as the centrepiece of a new exhibition at Old Melbourne Gaol museum. Someone ought to have signed Ned’s Head up to a frequent-flyer scheme, because just five years later it was on the move again, brazenly stolen from the exhibition in broad daylight.

Soon after, recluse Tom Baxter – who was of the belief the head shouldn’t suffer the indignity of being on public display – admitted he was in possession of the skull and had hidden it in a Tupperware container in the hollow of a log in the Kimberley.

Out of sight, out of mind. Authorities oddly resisted pursuing the matter further (in the 1970s there was no way of proving it was Kelly’s skull anyway) until 2009, when the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine (VIFM) announced an audacious plan to identify the remains of the prisoners – including those of Kelly – who had been exhumed at Old Melbourne Gaol and reinterred in a mass grave at Pentridge Prison back in 1929.

Baxter was convinced to return the skull, in the hope Ned’s Head could be reunited with his skeletal remains and given “a proper burial for a figure…[who] looms so large in our history and was persecuted by authorities”.

Flood, searing heat and age had all taken their toll on the relic; Baxter used araldite to patch up parts of the skull. “He never admitted to taking it, only that he was in possession of it,” says Fiona Leahy, a medico-legal advisor who was part of the VIFM’s multidisciplinary team comprising an eclectic mix of anthropologists, odontologists, pathologists, archaeologists, and just about every other ‘ologist’ you can think of. “So, we never really pressed him on it. We were just grateful that he brought it in.”

The sense of occasion hadn’t made Baxter treat the skull with any extra care. Rather than taking it in his carry-on and cradling it onboard the flight across the Nullarbor, he popped it in his checked-in luggage.

Subsequent DNA testing proved a headless skeleton exhumed at Pentridge was indeed Kelly’s. But in a bizarre twist – despite confirmation it was the same one displayed at the Institute of Anatomy in 1934 and later stolen from Old Melbourne Gaol in 1978 – the ‘Baxter Skull’ turned out not to have belonged to Kelly. What a revelation!

“The souvenir hunters likely targeted the wrong grave back in 1929, which means the skull could belong to just about anyone executed and buried at the gaol – although it’s most likely to be from a prisoner buried close to Kelly’s execution date of 1880,” says Jeremy Smith, principal archaeologist with Heritage Victoria.

So, where’s Ned’s Head now? There are more theories than there are ‘Such is life’ stencils in tattoo parlours around the nation. It’s a classic Australian whodunnit.

Craig has heard them all. “While he had sympathisers, we also know that Kelly was very unpopular in many circles, especially those dealing with the law,” he says. “Someone may have decided, ‘We don’t want him turned into a martyr, so we’ll get rid of it.’”

Then there’s this tantalising lead. “After the book was published, I had a priest tell me that he has it on good authority that Ned’s Head was buried by another priest, but he was sworn to secrecy,” Craig says.

If Ned’s Head, wherever it’s currently hiding, is reunited with the rest of his skeleton – which in 2013 was buried in an unmarked plot near his mother’s grave in country Victoria – it would provide closure.

But its missing status also adds another layer of intrigue to the legend of Ned Kelly that, whether you like it or not, continues to grow 145 years after his death.

‘Boxes & Burial Bones’, an exhibition featuring objects unearthed during Heritage Victoria’s landmark 2009 excavation of the mass grave at Pentridge, which included Ned Kelly’s bones, is at Pentridge Prison until 31 August 2025.