| Common name | Tasmanian devil |

| Scientific name | Sarcophilus harrisii |

| Type | Marsupial |

| Diet | Carnivorous eating wallabies, small mammals, reptiles, birds, and insects |

| Average lifespan | Around 5 years in the wild and 8 years in captivity |

| Size | 55cm – 65cm in length, 24-25cm long tail |

Feisty and frenzied, the Tasmanian devil is a true scavenger of the bush and holds the title as the world’s largest carnivorous marsupial.

Living up to its devilish name, this unique creature is known to fly into a rage if under threat, where it may bare its teeth, growl, and even lunge at would-be predators. Despite these wild personality traits, the Tasmanian devil is more often solitary and shy, preferring to keep well out of the spotlight (and boxing ring!).

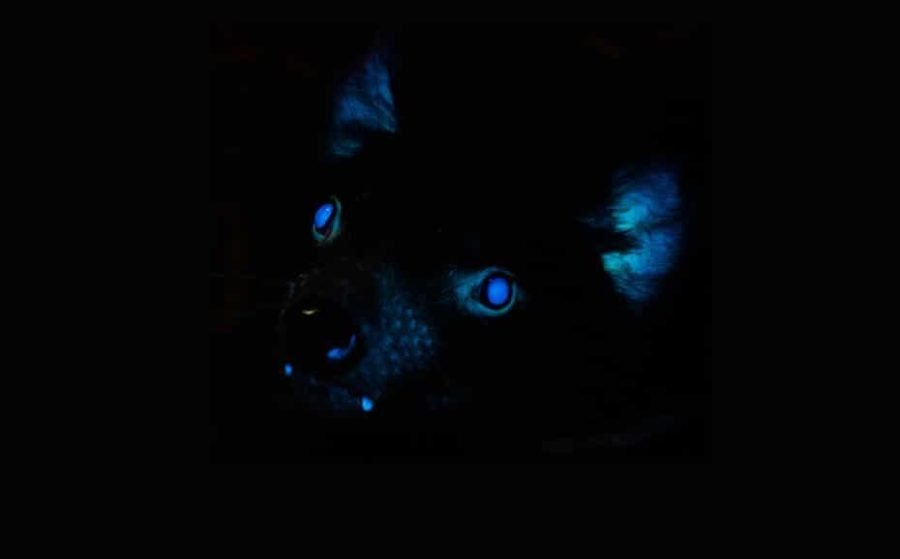

Around the same size as a small dog, these stocky marsupials have dark brown to black fur with a large white stripe across their chest and the odd white spot on their sides or rear end. The Tasmanian devil has longer front legs with thick, short hind legs giving the animal a lumbering gait when it walks. With a short muzzle, devils have long whiskers, dark eyes, and pink inside their ears.

Found exclusively in Tasmania, the Tasmanian devil is thought to have disappeared from mainland Australia around 400 years ago. While it doesn’t live on neighbouring offshore islands around Tasmania, there are some marsupials kept in captivity within other states of Australia. Across Tasmania, devils are found in all native habitats and make their homes in pastures, forestry plantations, open forest and woodlands that range from the coast to the highest mountain peaks.

Crafting their den in underground burrows, within thick grass tussocks and caves or dense riparian vegetation, the Tasmanian devil occupies a number of different dens, changing their home every one to three days and travelling on average 8km a night to do so.

Tasmanian devils leave nothing to waste and are mostly carrion eaters, which means they feed of dead animals. Primarily nocturnal, these specialised scavengers will eat the carcasses of a range of animals, but mostly possums and macropods, with some devils travelling up to 16km each night in search of food. The Tasmanian devil is also an opportunistic predator and will usually hunt solo, tending to prey on slow animals such as injured or sick wallabies or smaller livestock like lambs, using a combination of ambush tactics and pursuit.

With powerful jaws and sharp teeth, Tasmanian devils are well known to finish their meal in its entirety, gulping down flesh, hair, and even crunching bones. A dead animal carcass will often bring these solitary marsupials together, resulting in a noisy display of eating with the odd tussle between devils a given. Each individual devil will jostle for the premier dining spot or assert its dominance over the other animals during this raucous communal meal-time display.

Breeding once per year between February and June, the Tasmanian devil mates and then raises its young within its den. The female devil will give birth to more than twenty tiny juveniles, but with only four teats for feeding, only a few babies will survive. As a marsupial, the mother feeds her young within her pouch for up to four months, after which the joeys hitch a ride on her back for the next few months before being fully independent at nine months of age.

Now a protected species, the Tasmanian devil was once hunted in their thousands in the 1800s, by farmers concerned about their livestock. Although this stoic creature has survived, the Tasmanian devil is now listed as endangered under Tasmania’s Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 (May 2008). The red fox, low genetic diversity as well as deaths by road vehicles have threatened Tasmanian devil populations but the infectious, spreading cancer known as Devil Facial Tumour Disease is the main culprit for a decrease in devil numbers. Discovered in the mid 1990’s and spread through mating and fighting, DFTD sees tumours grow around the Tasmanian devil’s face and neck, ultimately stopping the animal from eating and causing a slow death from starvation often within six months.