| Common name | Australian paralysis tick |

| Scientific name | Ixodes holocyclus |

| Type | Insect |

| Diet | Blood and lymph of their hosts |

| Average lifespan | Up to 77 days without feeding |

| Size | Adults average 1cm in length |

The ultimate sucker of the insect world, the Australian paralysis tick is the stuff of nightmares for dog owners but can also prove deadly to a range of other animals, birds and even humans.

With over 74 species of ticks within Australia, only a few of these are harmful to humans, with the Australian paralysis tick packing the mightiest of punches with its bite.

This parasite is found on the east coast of Australia, from north Queensland down to southern Victoria. Thriving in humid conditions, the Australian paralysis tick makes its home within wet sclerophyll forests, in rainforests, gullies and regrowth areas and grassy spots near these habitats. In northern parts of Australia, this tick can be found all year round, but in the cooler southern parts, ticks are usually in season from Spring through to late Autumn.

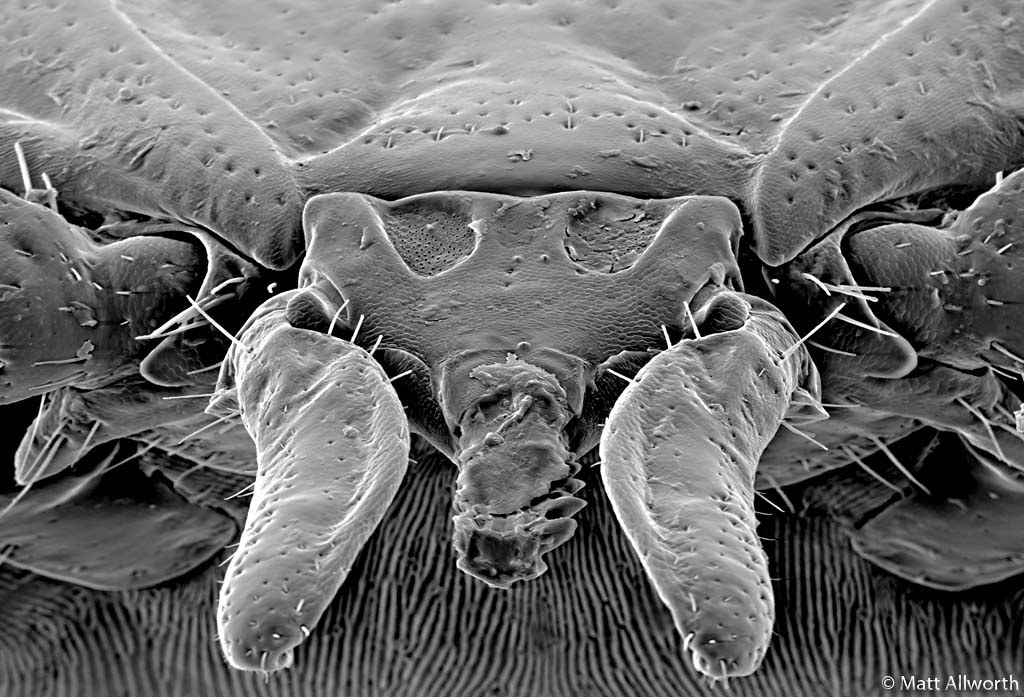

Just big enough to be seen by the naked eye when attached, the Australian paralysis tick is set apart from other common ticks by its menacing, long mouthpiece or ‘snout’ that has barbs along it, helping it to embed within its host.

Larvae have six legs with the first and last set darker than the others and nymphs and adults have eight legs like the rest of their arachnid relatives. With an oval or seed shaped body that is flat when empty, the legs are bunched up at the front near the mouthpiece and the body colour tends to change from whitish to grey to black depending on whether the parasite has fed or not.

Although male Australian parasite ticks sometimes crawl onto people, they very rarely feed on humans or other vertebrate hosts thanks to underdeveloped mouthpieces. Preferring to steal a bloody snack from their engorged female counterparts, the male can leave behind scars where it has pierced the female’s body wall in the plight of dinner. It’s the female tick that is the ultimate blood sucker. Lying in wait on vegetation with outstretched arms waving slowly, the Australian paralysis tick will then attach to a potential ‘host’ and penetrate their skin quite painlessly, thanks to an in-built pain killer within the tick’s saliva.

Bandicoots are among the more common mammal hosts, but the Australian paralysis tick has been known to embed itself onto birds, native mammals, reptiles, livestock, and domestic pets, as well as humans when the opportunity presents.

Tiny larvae or grass ticks feed on three different hosts to complete their lifecycle and move on to moult and enter the nymph stage, where they measure in at around 1mm. Feeding until they are completely engorged takes between four and six days and during feeding, paralysis toxins are produced and passed on to the host but only females and mostly those that have fed for four days or more produce enough toxins to cause paralysis in mammals or birds. Some native marsupial animals show a resistance, with bandicoots highly resistant to this toxin.

A bite from an adult Australian paralysis tick can cause itchiness and a hard lump at the site of the bite. For some unlucky victims, other immune responses can also occur, including allergic reactions such as weak limbs, flu-like symptoms, partial face paralysis and even anaphylactic shock.