On this day: Captain Moonlite’s hanging

WHILE NINETEENTH CENTURY bushranger Captain Moonlite’s biography is one of many adventures, continents and crimes, it is his final days that beg loudest for the Hollywood treatment.

Awaiting the noose on 20 January 1880 Andrew George Scott, or ‘Captain Moonlite’ as he was dubbed, spent much of his time in Darlinghurst jail in mourning. Not for his own life, but for the life of James Nesbitt, his fellow fugitive shot during the Moonlite gang’s standoff with police at Wantabadgery station two months previous. A well-educated man, Andrew wrote passionately in his last days, declaring his dying wish was:

…to be buried beside my beloved James Nesbitt, the man with whom I was united by every tie which could bind human friendship, we were one in hopes, in heart and soul and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.

His request wasn’t granted. Moonlite was buried at Sydney’s Rockwood Cemetery, while James was buried over 300km away at Gundagai, near where he had been killed.

Their relationship is a fragmented story – one which, from the vantage point of the 21st century, reads like love. But like much of his life – from his overseas escapades to his age – Moonlite’s public and well-recorded grief over James’ death leaves historians divided about the cause.

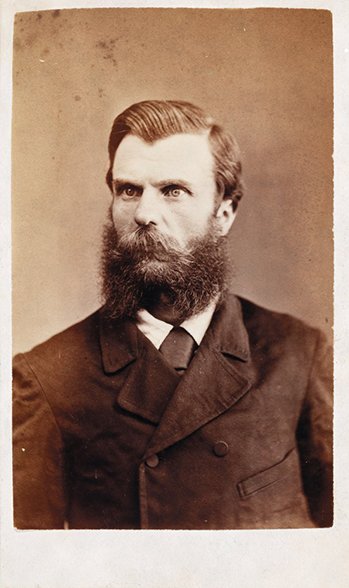

James Nesbitt, Australian bushranger. (Author unknown, public domain)

Moonlite: man and myth

But first; What do we definitively know about Andrew George Scott?

“He was what I’d call an accidental bushranger,” says Paul Terry, author of In Search For Captain Moonlite. “He wasn’t your typical smash-and-grab armed robber, holding up stage carriages. He was a white-collar criminal.”

Charming to dignitaries and degenerates alike, Andrew was born in 1842 into a respected family in Rathfriland in northern Ireland. He was educated – his father was an Anglican clergyman, and as a teenager Andrew studied engineering in London.

Then, things get murky – before moving to Auckland with his family in 1861, he may have fought in both Italy’s second war for independence and then later in the American Civil War, though Paul is sceptical about these facts.

“This early period is where we know the least about Moonlite, so while it’s possible, there’s also a lack of real evidence,” says Paul. “Let’s put it this way: I’d be surprised.”

Paul points towards two sources of these myths – Captain Moonlite, a 1970s ‘potboiler’ by George Caulderwood whose narratives have been mistaken for fact, and Andrew himself.

“He was a very dishonest person,” says Paul. “It wouldn’t surprise me if he’d went around bragging about stuff he hadn’t done. And he was so outrageous and flamboyant and articulated and educated that people listened and they liked to talk about him. So the rumours spread.”

In Auckland, Scott was recruited to the military during the Maori Wars, where rising the ranks proved difficult despite his social ease. In 1867, due to an unknown ‘scandal’, he was refused a promotion and left for Australia.

At first, Andrew followed his father’s lead by preaching in regional Victoria. However scandal seemed to find him, or he it. In Bacchus Marsh, west of Melbourne, Andrew became was intertwined in scandal surrounding a cattle theft, which forced a move to Egerton. There, ‘Captain Moonlite’ was born when a disguised Andrew attacked his friend and bank employee L. J. Bruun in a robbery that may have been staged by the two men. A note with a deliberately mis-spelled name was left behind to misdirect the law.

But this was not enough to evade suspicion, so Moonlite left for Fiji. There he lived off fake cheques on a stolen yacht. According to Paul, during this period he had an affair with photograhper Alan Hughan, from whom he later stole money.

After returning to Sydney, Moonlite found himself in and out of prison. First, he spent a year imprisoned at Maitland for the boat theft. For some of that time he feigned insanity and was kept at Parramatta Lunatic Asylum. Then, when released in 1872, the Edgerton bank robbery caught up with him and he was sentenced to jail for another 10 years, with an additional year for escaping prison while on remand.

It was in Pentridge jail that Andrew met James Nesbitt. Released a few years early in 1879, Andrew lived in the Melbourne suburb of Fitzroy with the 21 year old. By this stage, Moonlite was a well-known public figure; a bushranger.

Mateship, or more?

Moonlite’s post-jail career speaking on prison reform was brief, as authorities did not approve. With notoriety, he found it hard to get a job, or, at times, lodgings.

Three poor young men, two in their teens, joined Andrew and James as they travelled between towns, committing petty crimes to feed themselves. Starved and frustrated, on 18 November Moonlite’s gang held up Wantabadgery Station. Two men would die in an inevitable police shootout: Senior Constable Edward Webb-Bowen, of whose murder Andrew and two of his accomplices were found guilty, and James.

Andrew’s grief at James’ death was reportedly palpable. One journalist later described it in a book, suggesting that Andrew had been heedless of the firing and had carried Nesbitt inside where, as James died, “his leader wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately”.

It was this description that piqued LGBT historian Garry Wotherspoon’s original interest in Captain Moonlite, spurred on by reports of Moonlite’s trial detailing how he became agitated whenever James’ name was mentioned. In 2004, he discovered a bundle of letters Andrew wrote in the Darlinghurst jail, laying forgotten deep in New South Wales’ state archives.

“They were never sent,” says Garry. “They were filled with so much passionate language about James.”

But while Moonlite’s declarations such as “his death has broken my heart” seem obvious in their meaning, Garry reminds us the 19th century’s view of affection between males is very different to our own, and he’s hesitant to label Captain Moonlite’s sexuality.

“There was no concept of gay or straight in the 19th century,” says Garry. “In terms of their relationship, many men at the time had what we would now consider very intimate or overtly close friendships without anyone finding this very terribly odd.”

“Even the ring of James’ hair that Moonlite was known to wear – it simply wasn’t as odd as it seems today.”

It wasn’t until the turn of the century that society began to identify and characterise homosexuality in a way that would make such expressions uncomfortable or unseemly. In the 1890s, Sydney newspapers began referencing the ‘Oscar Wildes of Sydney’, referencing the existence of homosexuals in society through roundabout language.

“It was really the Oscar Wilde [sodomy] trials in 1895, and the salaciousness and mass coverage of them that made men uncomfortable with affection. That was the beginning of a more realised homophobia,” says Garry.

Shortly after the English writer’s imprisonment for sodomy, effeminate men or anyone not fitting into a rigid idea of manhood could expect to face public persecution. But in the 1880s, it’s unlikely even a kiss was understood or meant in the same way, Garry says.

But Paul is not so sure. “Even allowing for that 19th century floweriness language,” he says, “Moonlite wrote such romantic words about James that I’m sure as I can be that it was a homosexual relationship, or at least a romantic one.”

Thanks to activists, in 1995 the two were laid together, when Andrew’s body was re-interred at Gundagai cemetery. More than a century after they were, in Andrew’s words, “separated by death”, the pair was re-united.

READ MORE: