On this day: Mt Kosciuszko put on the map

ON THE EVENING OF 12 March 1840 Polish geologist Sir Pauł Edmund de Strzelecki left his expedition party behind and made the final ascent to summit of the highest peak in Australian alone – or so he claimed.

For more than a century subsequent, a cartological debate raged as to whether Strzelecki actually scaled Mt Kosciuszko (2228m) or nearby Mt Townsend (2209m), though consensus has since sided with the Polish count.

In Strzelecki’s account, he parted with prominant grazier James MacArthur on the peak of Mt Townsend when his surveying equipment revealed a higher massif several kilometres away.

Uninterested in continuing, MacArthur returned to supper being prepared by their Aboriginal guides Charlie Tarra and Jackey at base camp. For him, the expedition was purely a commercial exersize in looking for suitable territory to expand his sprawling landholdings.

Strzelecki would return in darkness hours later, bruised from several falls, but having added the ascent of Australia’s highest peak to a growing list of impressive achievements.

Flying the Polish flag on the roof of Australia

Arriving in Australia in 1839 and departing in 1843, Strzelecki covered more than 11,000km of Australia in over four years. Many geological features bear his name, from the Strzelecki Desert in South Australia to the Strzelecki Ranges in Victoria. He was among the first Europeans to lead expeditions into these regions.

From Chile to Canada, Hawaii to Tahiti, Strzelecki had already travelled the world, pioneering the sciences of geology and mineralogy. After returning to Europe he would recieve a Gold Founder’s Medal, Fellowship of the Royal Geographical Society and in 1869 a knighthood from Queen Victoria.

Strzelecki dedicated the Kosciuszko expedition to two of his compatriots, with one private and one very public homage.

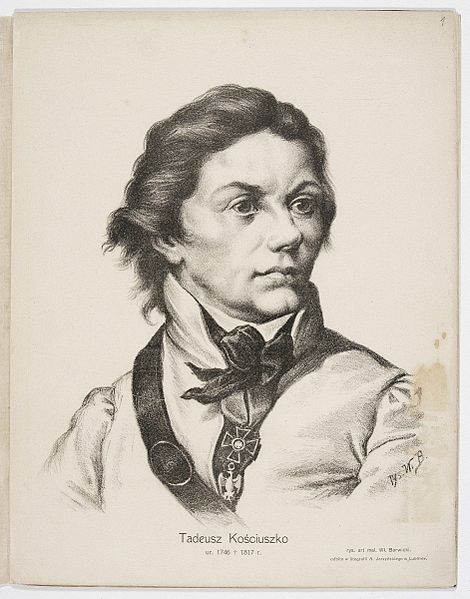

The mountain he named in honour of a military hero of both the American and Polish revolutions, and a staunch supporter of slave and serf emancipation: Tadeusz Kościuszko. A white daisy picked on its peak was pressed and sent to his lifelong sweetheart, Adyna Turno. Separated after youthful romance, the two maintained correspondence but never met again until he they were in their 60s. Neither married.

While Turno waited stoically for Strzelecki in the homeland, he was building an international reputation – at once dandy, intellectual, humanitarian and patriot.

Tadeusz Kościuszko. (Courtesy National Digital Library Polona)

Polish charmer and chancer

In a 2010 article in The Monthly, author Shane Maloney and Chris Grosz wrote of Strzelecki’s chance encounter with the Lady Jane Franklin at a dinner party in Sydney’s Government House.

The wife of Van Diemen’s Land Governor James Franklin, Lady Franklin is credited with making Tasmania the intellectual centre of the Australian colonies during her husband’s term of office. In a letter to a friend, she wrote she was “enchanted” by the Polish count’s elegance, cleverness, fire and vivacity.

Manners, breeding and exotic tales made Strzelecki a hot ticket in dining halls and academies the world over, Shane says.

“He was a bit of a charmer and a bit of a ‘chancer’ and incredibly intellectually curious,” Shane says.

Part of the Polish diaspora

Strzelecki’s patriotic cause added to his allure. Inspired by Kościuszko and the American Revolution, Poland was the second country in the world to adopt a constitution. It was an act which quickly drew the ire and armies of its powerful neighbours and saw Poland cease to exist as an independent nation for more than 120 years.

“It was one of the great romantic causes of the 19th Century,” Shane says. “Strzelecki was going round hoisting the flag for Polish nationalism at a time when the Polish nation didn’t really exist, but resided in the imagination at fancy dinner parties and in this particular class of people in the Polish diaspora.”

But the count was not all fancy dinner parties. A plaque to be unveiled later this month in Dublin will honour his role as famine relief agent in Ireland’s Great Famine.

From 1846 to 1848, Strzelecki put his organisational skills and energy into the philanthropic effort as Ireland was ravaged by mass starvation and disease. Strzelecki refused payment from the Crown for his work, though he was appointed by her Majesty an ordinary member of the 3rd Class of the Civil Division of the Bath.

Strzelecki connecting Polish-Australians to Kosciuszko

Today, the Polish community in Australia continues to champion the ideals of their two forebears associated with Snowy Mountains.

Andrzej Kozek, a member of the Kosciuszko Heritage organisation, says he views Australia’s highest mountain as a cultural monument akin to Kosciuszko Mound in Krakow, after which the Australian peak was also named.

“Kosciuszko fought for equal rights for all people of all races and all religions,” Kozek says. “He is a symbol for values which are so cherished today in Australia and we try to keep this legacy and our cultural heritage alive.”

Kosciuszko Heritage also maintains a relationship with the traditional owners of the Australian Alps. Kozek says the skills of guides Tarra and Jackey were crucial to the success of the Strzelecki’s expedition, as was their respectful relations with the tribes whose lands they passed through. This included the Ngarigo, who would visit the Snowy Mountain highlands in warmer months to feast on hordes of migratory Bogong moths.

“We meet with the Ngarigo people at NAIDOC week and always invite them to festivals we hold in Jindabyne,” Kozek says. “It is for us important to stay in touch and continue the tradition of Kosciuszko and Strzelecki.”