The Varroa mite is here to stay

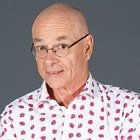

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki

It’s tiny, about the size of a sesame seed, and it feeds on a bee’s fatty tissues. An infected bee would be similar to a human carrying a parasite sized between a bagel and a frisbee. A Varroa-infested bee has a reduced ability to fly, pollinate crops and carry food. When enough of its bees are infested, a hive dies.

The first Varroa mites of consequence in Australia (previous minor infestations were eradicated) were found in New South Wales, near Newcastle, in June 2022. They have since been detected south near the Victorian border, and north around Coffs Harbour. The official policy has changed from “containment and eradication” to “management”.

Bees benefit our human food ecosystem in many ways – such as providing honey. The recreational beekeeper, with a single hive, might collect honey for family and friends. But commercial beekeepers, often each with hundreds of hives, together produce honey worth about $0.25 billion/year.

Importantly, however, bees can also pollinate flowering crops. That’s a 14-billion-dollar industry, dwarfing the honey industry. For example, almond pollination (in south-western NSW and north-western Victoria) is huge.

Almonds have a short flowering time of about a month. Some 15 per cent of Australia’s 700,000 beehives get shipped in semi-trailers to NSW’s Riverina and Sunraysia areas in August each year. They’re then shifted to pollinate canola, and so the cycle goes.

The Varroa mite is here to stay.

Many recreational beekeepers will have to shut down when the cost of management due to the mite becomes too high. Commercial beekeepers will almost certainly survive, but their costs will increase.

In 2018–19, Australian agriculture generated $62 billion – and bees contributed to about one-third of that. About 20-40 per cent of Australian agriculture depends on feral/wild bee pollination. But this will probably mostly disappear, and farmers will be impacted. New Zealand went through their initial Varroa mite infestation in about 2000, so many farmers now keep managed hives on their property to pollinate their crops.

Australia is starting with a clean slate to deal with the Varroa mite, and has a chance to develop an integrated National Strategy.

RELATED STORY: Australia gives up on eradicating varroa mites

RELATED STORY: 200 years since the honey bee came to our shores, it’s hard to imagine an Australia without it