The northern river terrapin’s breeding colours are not subtle

Bec Crew

Bec Crew

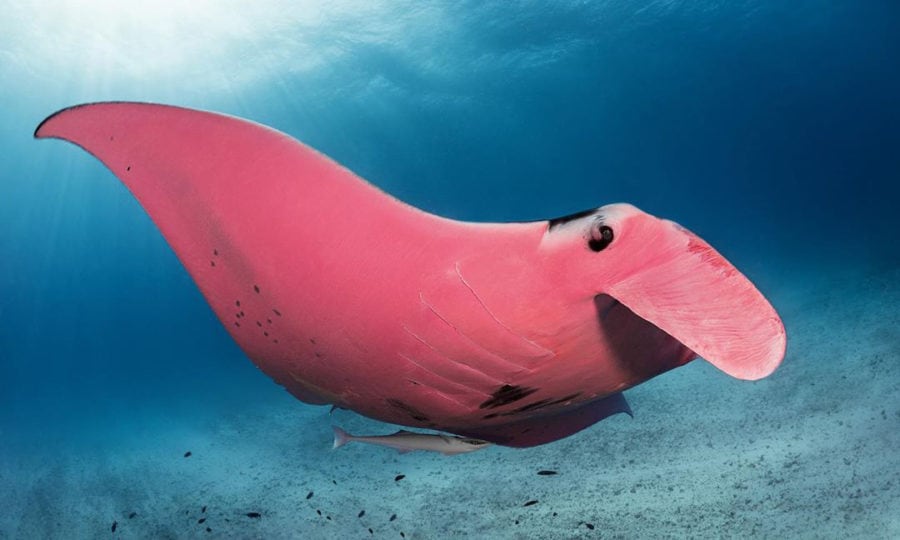

Sporting a tiny head, beady eyes, and a long, upturned snout, the northern river terrapin is a sight to behold, even without its breeding colours. With its breeding colours, it looks like one of those grotesque ‘real’ Pokemon, which are honestly just really upsetting.

Why do species like the northern river terrapin (Batagur baska) suddenly manifest bright, highly contrasting colours during the breeding season?

In 2017, scientists from UNSW in Sydney and the University of California, Berkeley, studied the phenomenon in more than 100 species of frogs. Many species of frogs breed in large, chaotic groups, and it’s thought that the males’ breeding colours help them stand out to the females among the crowd.

They might also help them stand out to the other males – a “Don’t mount me” signal, if you will.

The same could be true for the northern river terrapin, which usually looks like this:

Look at that creepy little smile.

If only its breeding colours could also say, “Stop that, we’re related!”, because northern river terrapins are so rare these days, many of them are.

Found in the estuaries, rivers, and mangrove forests of South East Asia, including in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Cambodia, the northern river terrapin is one of the most endangered turtles in the world.

It’s already been declared extinct in Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, and is “functionally extinct” elsewhere in the wild, which means the species no longer has enough individuals to produce a sustainable future population, or play a role in their local ecosystem.

Although northern river terrapins are believed to live for up to 100 years, most don’t make it even close to that in the wild, because poachers consider their shells, meat, and eggs a real commodity.

According to the World Economic Forum, females are traditionally the most sought-after. Fishermen can get up to US$365 for a female, which is twice the average monthly wage in Bangladesh, for example. When sold on the black market, they can fetch significantly more.

That’s why captive breeding programs, such as those in Bangladesh and Austria, are so important. And the good news is northern river terrapins breed well in captivity. Recent reports suggest that those that have been released back into the wild in Bangladesh are thriving. But we have a long way to go before these wonderful turtles are out of the woods.

Find out more about them below: