A mission to save indigenous languages

HIDDEN IN THE MANUSCRIPTS of early British settlers are the last surviving records of many indigenous languages. Last week, the State Library of NSW launched a new project to rediscover these forgotten dialects.

Of the 250 indigenous languages spoken at the time of British settlement, fewer than 20 are still in daily use. The State Library of NSW, in a partnership with Rio Tinto, aims to pass the rediscovered words on to Aboriginal communities, helping to reverse the current language decline.

Melissa Jackson, an indigenous services librarian at the State Library, says early recordings of lost languages can be found among the journals and letters of British naval officers, missionaries and surveyors. But poring over the Library’s vast collection of manuscripts is a daunting task.

“The first phase of the project is discovering what language lists we hold in the Library’s twelve linear kilometres of manuscripts,” Melissa told Australian Geographic. “The lists can be in the form of a formal study into Aboriginal languages, or they can just be snippets of information in someone’s journal.”

Cultural regeneration – the process to revive indigenous language

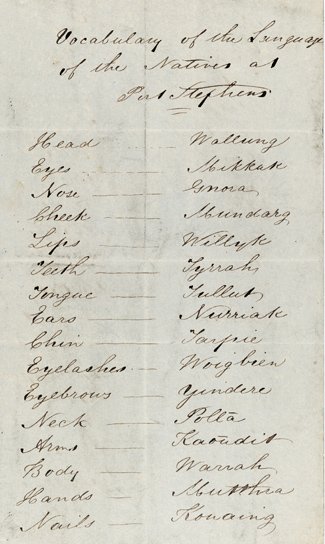

For example, Charles Macarthur King, the grandson of a NSW Governor, recorded 55 words from the language of the Port Stephens people on a few loose sheets of notepaper. Inscribed in about 1845, the words are grouped into body parts (wallung is head), animals (womboin is kangaroo) and the physical environment (unthimum is thunder and pingus is lightning).

The second stage of the project involves consultation with Aboriginal communities to make the words available online. “It’s not only finding the significant languages but making sure the community’s happy with the way we’re presenting the material,” says Melissa.

The final stage, she says, will be to develop new education programs that teach the forgotten words to primary and high school students. “What we want to do is assist the cultural regeneration by teaching people how to learn those languages through our education programs,” she says.

Susan Poetsch, a linguist and teacher of indigenous languages from the University of Sydney, who is not involved in the project, believes the work will have wide-reaching benefits. “There are people who are partial speakers or remembers of the language, and their knowledge can be supplemented by information that was collected in earlier decades,” Susan says. “Language revitalisation is very important both to Aboriginal communities and to the wider Australian community – not only for community identity but for cross-cultural understanding…The languages are a window to the culture and the world views that are held by Aboriginal people.”

© Australian Geographic, unless otherwise indicated. This material may be used, reproduced, published and adapted free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes.

RELATED STORIES