Neat rows of parallel sand dunes stretch on for miles in the vast Simpson Desert. Occasionally, though, a desolate plain opens to the horizon between these sandhills. We’re driving through one of these plains right now, following a straight track that seems to aim at infinity. Fluffy clouds litter the sky, leftovers of a rainband that moved through two days ago.

Then, animated by shimmering heat radiating off the ground, something resembling a rickety picket fence appears far ahead. The strange apparition on the horizon is a stand of trees. They are Acacia peuce, also known as waddi trees or waddywoods, among the world’s rarest trees. Only three stands – including this one in the Mac Clark (Acacia peuce) Conservation Reserve in the west Simpson Desert – are known to exist in Australia. Slim and tall, the slow-growing trees are thought to be left over from the last ice age, surviving ever since in the harsh desert environment.

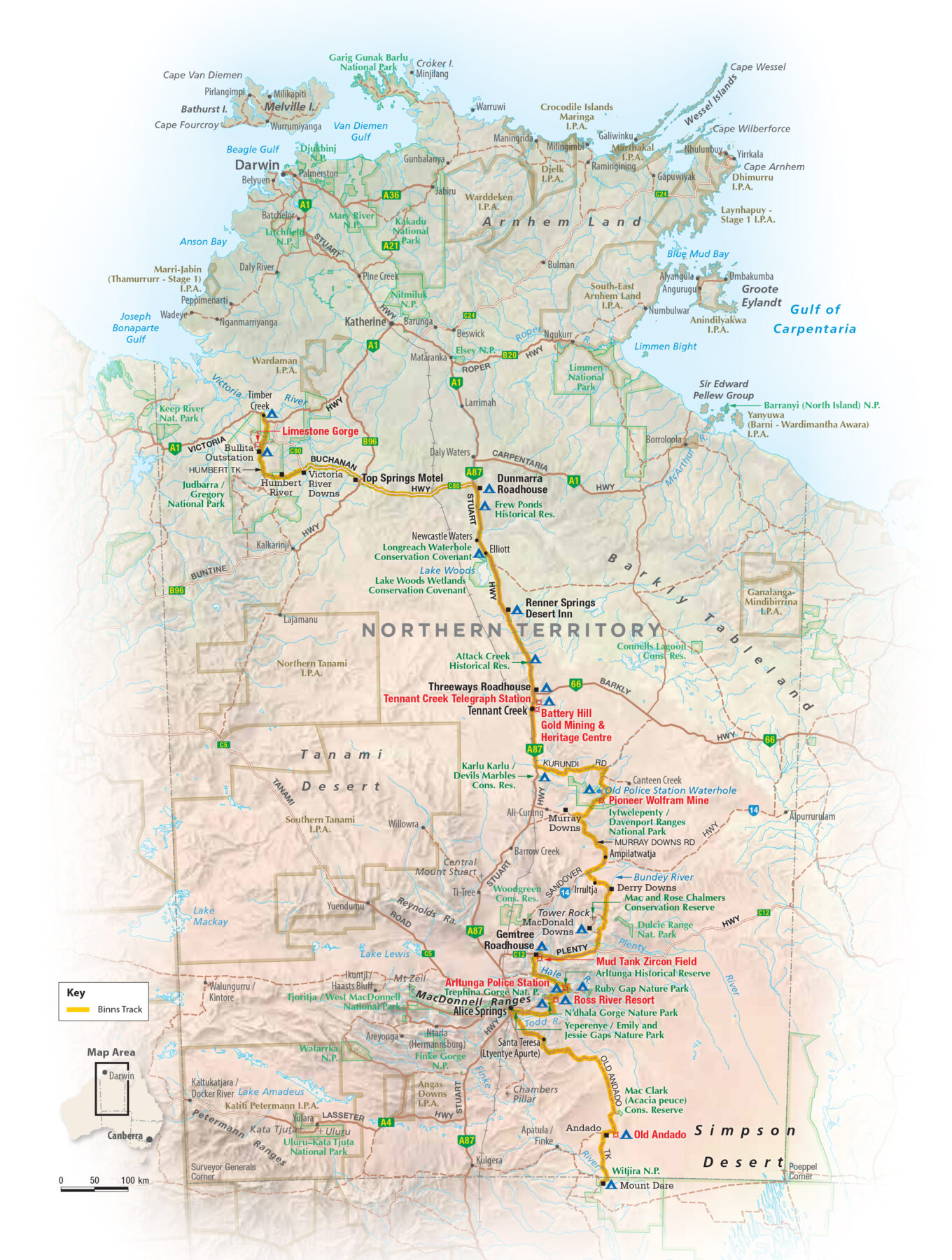

The reserve, which sits in the Northern Territory 150km north of Mt Dare, is just one of many unusual attractions along the Binns Track, a 2230km-long outback driving route. Mt Dare is the home of a quirky outback pub just south of the NT-South Australia border that acts as the starting point of this four-wheel-drive adventure, which ends at Timber Creek in the far north-west corner of the NT. The track is named after Bill Binns, a ranger who worked with NT Parks and Wildlife for 32 years. His vision was to make some of the NT’s lesser-known attractions more accessible to adventurous visitors.

Mt Dare Hotel is one of Australia’s most isolated pubs and has been managed by Shaynee Lee Scott and David Mark Wood since 2015. Situated in the remote north-west corner of Witjira National Park, they offer accommodation, meals, mechanical and tyre services, fuel, and recovery and emergency medical responses. The pub also serves as the local knowledge bank for track conditions along the southern part of the Binns Track.

“Mt Dare is now known as the place to come if you want to know what’s really going on,” Shaynee says. “We recommend [to] a lot of people to try the Binns Track. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the most beautiful track out here. The landscape is so diverse. At one point you feel like you’re driving through the Murray with big, white gums. Then you got gibber plains. Then you got the ranges. You’ve got Old Andado. There’s a lot of history.”

The Simpson Desert defines the first part of the Binns Track. The day we leave Mt Dare, the desolate plains leading to the border and beyond are cloaked in an eerie mist that has burnt away by the time we enter the dune fields. Past the occasional stretch of gibber plains, where small, polished and burnished pebbles form a protective layer over fragile sand, the route continues to Old Andado. The last occupant of this historical homestead was Molly Clark, who died in 2012. Her furniture and belongings are still inside the ramshackle building, exactly as she left them. Only the silence and a thin coat of red desert dust remind you that this is a time capsule, a relic of a bygone era.

Ian Clarke, a business manager from Alice Springs, frequently visits Old Andado. His ties to the remote outback station run deep – after experiencing job burnout, he worked as a bore runner there from 2009 to 2010. “I looked after the water for the cattle,” Ian says. “I would do 2000km a week across sand dunes, gibber plains, through the bulldust to check every bore.”

The Old Andado Station formed part of Ian’s bore run. “I would stop here and start the bore, fill up the water, and water the garden,” he says, adding that his stint as a bore runner helped him heal. “Out here, the weight lifts off your shoulders. I come into the desert and I’m home.” Ian still looks after the homestead as a volunteer.

North of Old Andado, the Binns Track traverses vast sandhill country. Vegetation covers the sand dunes and a rich bouquet of wildflowers is on display.

After the desert come the mountains. The Central Ranges, an arid ancient landscape dominated by rugged quartzite peaks and bisected by dramatic chasms and gorges, form the next stage of the journey. Within these ranges lie some of the Binns Track’s most memorable highlights: the former Catholic mission of Santa Teresa (Ltyentye Apurte); the East MacDonnell Ranges with Yeperenye / Emily and Jessie Gaps Nature Park; and N’Dhala Gorge Nature Park.

Ancient history is the main attraction at N’Dhala Gorge. Almost 6000 First Nations rock carvings have been registered in the park. Most are faint, worn by time and weather. It’s a beautiful, tranquil place. There’s still water in sections of the creek when we walk into the gorge. Wildflowers have blossomed. The smell of dew on dry grass and a whiff of honey wafts through the air. The undoolya wattle or sickle-leaf wattle (Acacia undoolyana), a rare species found only in small isolated stands around here, is in full bloom.

The history embedded in this stunning scenery now shifts from ancient to modern. Within the Central Ranges lies Arltunga Historical Reserve, an abandoned goldmining locale that was the first officially recognised town in Central Australia. Some of its buildings – including the Arltunga Police Station and the lock-up – have been renovated and stand as a testimony to the gold rush that began in 1887, when traces of gold were found in nearby creeks. Soon after the first alluvial gold was found, prospectors discovered veins of gold-bearing quartz in the White Range.

Predating the gold, however, was a rush of prospectors heading to Ruby Gap, situated some 40km east of Arltunga. Their hope of finding rubies there was short-lived when the red crystals found in the Hale River’s bed turned out to be semi-precious garnets.

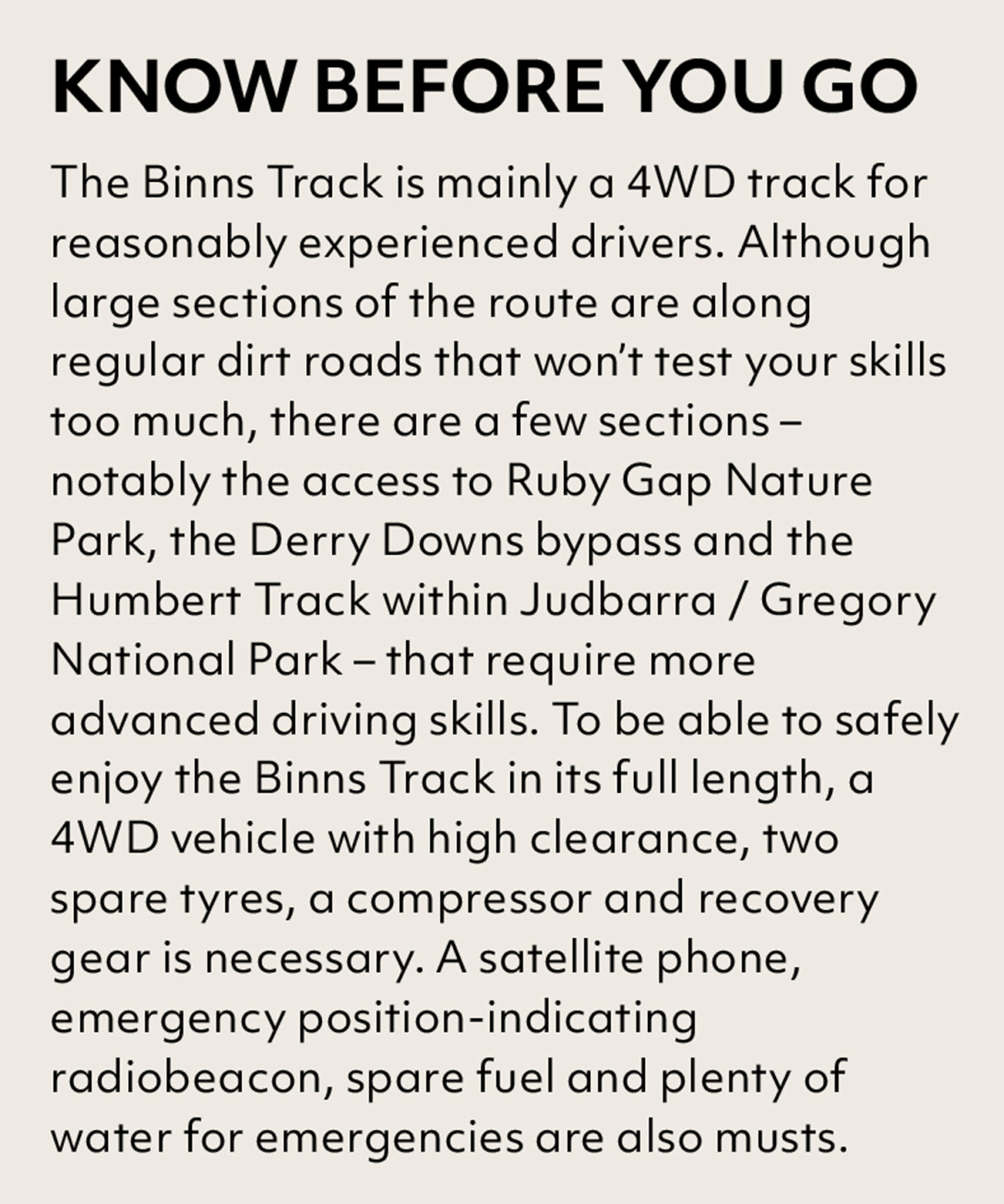

Ruby Gap is accessible via a detour from the Binns Track. On this side trip, drivers face their first 4WD challenge to access this stunning gorge due to deep sand in the riverbed that can create tricky conditions. We pitch our tents above the Hale River, shaded by towering cliffs. In the morning and evening the rock walls glow and reflect in pools in the riverbed. Flocks of budgerigars rush through stands of old river gums, and there’s always the chance to spot a rare rock wallaby.

Cattle, not rock wallabies, are the indicators of another change as we continue north. Long stretches of the Binns Track now run through station land. The topic of the region’s mineral riches, however, lingers.

Gemtree Roadhouse, 120km north-west of Arltunga, is an important fixture along the Binns Track. Owned by Alex and Cameron Chalmers, it has a campground and caravan park, accommodation ranging from ensuite rooms to cabins, fuel for drivers, and even a gem room where visitors can purchase all types of gemstones. There’s a reason for the latter. “The Mud Tank Zircon Field, which is about 18km by road from here, is the largest deposit of zircon in the world,” Alex says.

Gemtree organises tag-along tours to the gem field. “Our guests follow in their vehicle and we take them out to an area on the zircon field,” Alex says. “We show them how to fossick and how to recognise the zircons in the rough. When the guide is comfortable that they can find their own zircons, they are welcome to stay out in the field.”

Alex grew up on MacDonald Downs, a large station about 180km north-east of Gemtree. On the station is the Mac and Rose Chalmers Conservation Reserve, also known as Tower Rock. He describes Tower Rock as “the Devils Marbles on steroids”. Rising out of the flat station land are hills of large, rounded granite boulders, as if a playful giant had collected some rocks and left them in big piles.

“The reason why it’s a reserve is primarily because of Mum and Dad being buried there,” Alex says. He explains that after negotiations with local Traditional Owners, for whom Tower Rock is also important, “they declared it as a Chalmers sacred ground”. A flora and fauna survey of the 470ha reserve, undertaken by national parks, later confirmed the area’s conservation value.

Along the stretch between Tower Rock and the next highlight, Iytwelepenty / Davenport Ranges National Park, the sense of remoteness and isolation is now a steady companion. That feeling intensifies on the rough track that bypasses Derry Downs. This bypass, another test for 4WD drivers, is rough, alternating between sandy creek crossings and rocky passages. Deep washouts add spice. In some places, the bypass consists of two sandy ruts bordered by blue mallee and spinifex.

Some 260km farther along, the headframe of the Pioneer Wolfram mine, shut down in the 1970s, signals the proximity of Iytwelepenty / Davenport Ranges National Park. Protected within the borders of this 1120sq.km nature reserve, the water-rich Davenport Ranges form a transition zone between the arid southern NT and the higher rainfall country to the north, creating an important refuge for fauna and flora.

Tonight’s camp is the Old Police Station Waterhole. Large river gums form a riparian corridor that lines its banks. In the evening, corellas settle in pairs on tree branches, illuminated by the warm glow of the campfire.

cherished sacred site and living cultural landscape.

The Binns Track changes dramatically 163km west of the waterhole, where it reaches the sealed Stuart Highway. Bitumen replaces dirt. The sense of remoteness fades. A short detour to the Karlu Karlu / Devils Marbles drives home this new reality; Binns Track travellers now share the road with non-4WD tourists.

Described as a ‘living cultural landscape’, this extraordinary collection of large granite boulders is registered as a sacred site. Cultural sensitivities have led to a few restrictions: some rock formations can’t be photographed, the rocks shouldn’t be climbed, and visitors are asked to stay on walking tracks.

Almost 460km of bitumen lies between the Devils Marbles and the turn-off onto the unsealed Buchanan Highway. Dominated by road trains and caravans, the undulating grey band of the Stuart Highway leads through an epic landscape. The vegetation here is noticeably denser.

About 114km from Karlu Karlu is Tennant Creek. With its well-stocked supermarket and many other services, this town is an important stopover along the Binns. One of its residents is Dutch-born Martijn Weezepoel. He arrived at Tennant Creek 15 years ago as a backpacker on a working visa and is now an Australian citizen. He loves living here. “It’s a small town. People watch out for each other,” he says.

Tennant Creek was built on mining. “The last great gold rush in Australia was here in 1932,” Martijn says. All mines are now shut, and Tennant Creek survives as an Aboriginal service town. Mining exploration, however, is ongoing. “They’re thinking that there’s at least $30 to $80 billion worth of gold, silver, copper and anything else; but more importantly, cobalt,” he says. “We might actually become a boom town again.”

Like Alice Springs, Tennant Creek has had its share of problems. Martijn is quite clear-eyed about its negative image and the troubles the town has faced. “It’s not all sunshine and roses,” he says, and identifies lack of housing and bored kids as the main sources of the problems. There’s a silver lining, though. “Now that the youth centres are working, it’s much better,” he says. “It’s not as bad as people are making out.”

The Battery Hill Gold Mining & Heritage Centre, the Barkly Regional Arts Centre and the Tennant Creek Telegraph Station are all worth a visit. So is Newcastle Waters, a historic township en route to the Buchanan Highway. Named after semi-permanent waterholes, this heritage-listed ghost town was established in the early 20th century as a drover supply point. The township was abandoned in the 1960s, when road trains replaced drovers.

Another 84km farther along, the Buchanan Highway branches off to the west and the Binns Track is back on dirt. This unsealed road connects the Stuart Highway with Victoria River Downs Station and, ultimately, the sealed Victoria Highway near Timber Creek. Attractions are sparse along the Buchanan Highway, but with the crossing of the Victoria River the adventure notches up again. About 47km west of the station, the Humbert Track leads into Judbarra / Gregory National Park, the NT’s second-largest reserve. The park is the Binns Track’s grand finale. The Humbert Track leads through open savanna country, past impressive stands of boab trees, to Bullita Homestead. The historic homestead and cattle yards, the epicentre of the park, are just 64km from the northern end of the Binns in Timber Creek. They’re a testament to the tenacity of the early settlers who eked out an existence in this harsh country.

About 20km from Bullita is Limestone Creek, where four park visitors are whiling away the hot afternoon hours in the shade of trees. Behind them, Limestone Creek forms pools created by tufa dams. These natural dams are built from porous rock formed by calcite deposits. “This is an oasis,” says park visitor Wayne Burg. It’s likely the only safe swimming hole in the park; signs throughout the reserve warn the rivers and waterholes here are home to saltwater crocodiles.

The Limestone Creek area is a geological wonderland. Besides the tufa dams there are stunning karst formations and a unique calcite flow, a ‘frozen waterfall’ of glittering white calcite deposits. For Wayne and his party, the little-known park is new ground for adventures and a bit of a challenge. “All the tracks seem to be pretty rough,” Wayne says. “Go slow, don’t hurry, take your time.” It’s advice that should apply to the entirety of the Binns Track.