It’s described as the world’s longest-running marine cull – an almost century-long massive loss of aquatic life along Australia’s coastline linked to shark nets.

First introduced during the 1930s and still deployed along parts of coastal New South Wales and Queensland, shark nets have been sold to the public as protection for swimmers and surfers. But they’ve long been criticised by scientists for both their shortcomings in safeguarding humans and the unchecked harm they cause to marine life. “Relics of another era” and “the most dangerous thing in the water” is how they’re described by Australian Marine Conservation Society shark scientist, Dr Leonardo Guida.

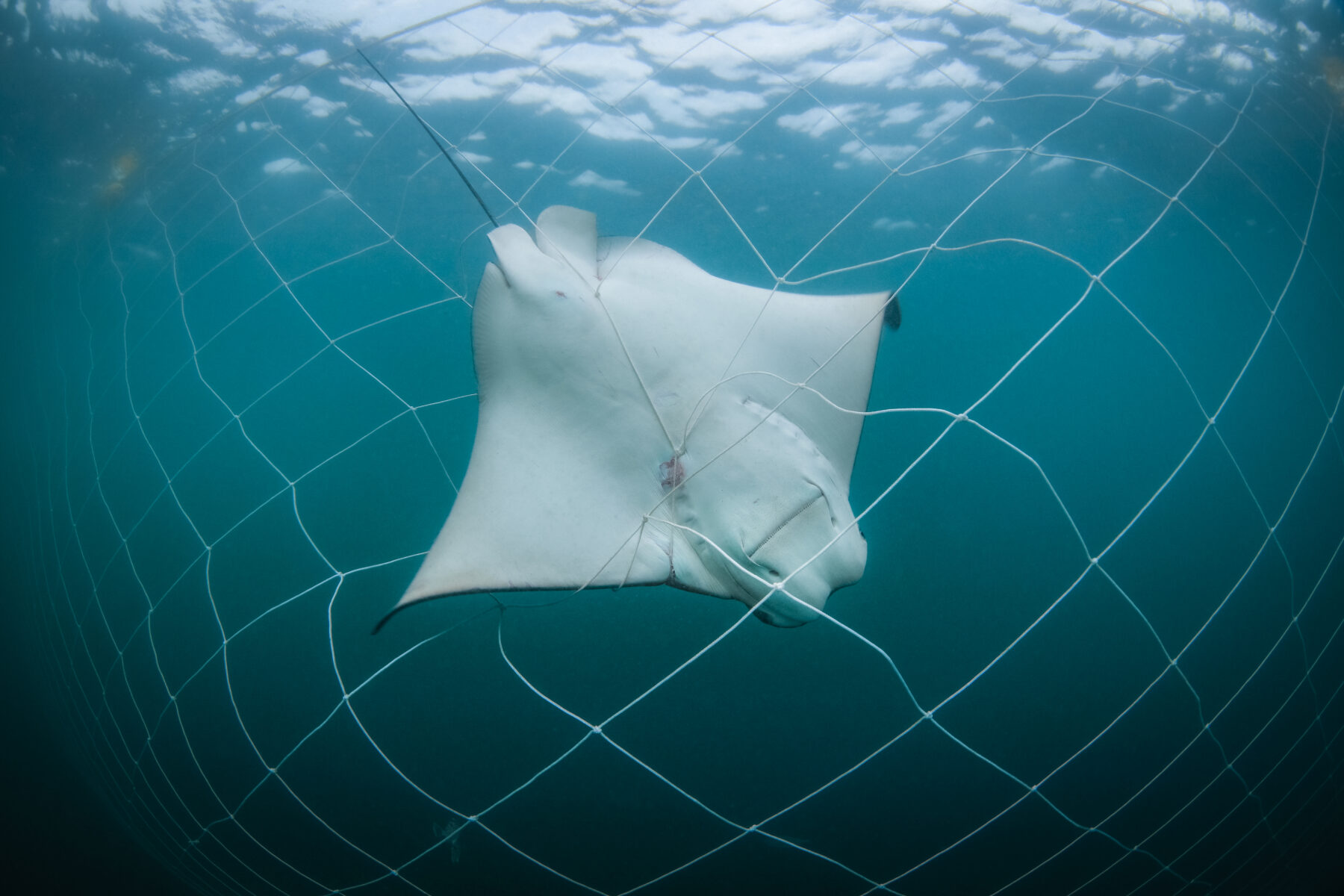

Contrary to popular belief, the nets aren’t barriers to sharks. Each net is about 150m long and 6m deep, leaving plenty of surrounding space for the sharks they target – such as great whites, tigers and bulls – to swim over, under or around. Designed to function by catching sharks through entanglement rather than by exclusion, they end up trapping far more than only sharks.

Figures recently released under Freedom of Information to Humane World for Animals, formerly Humane Society International, have yet again shown the overwhelming failure of NSW’s shark nets with almost 90 per cent of the animals caught during the 2024–25 season being non-target species. Tragically, 67 per cent of the animals caught died. These include dolphins, whales, turtles, dugongs and seabirds, as well as threatened shark species such as the grey nurse shark, which is critically endangered on the east coast.

Although nets do their damage passively, they’re only part of the story. Queensland also relies on another control tool: drumlines. Unlike a barrier, drumlines are floating buoys rigged with baited hooks that offer a free feed to attract large sharks into popular swimming areas while indiscriminately catching anything that takes the bait.

In Queensland, all target shark species – white, tiger, bulls and more – caught on drumlines and nets are euthanised, except for those inside the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, which are tagged and released whenever possible. Until recently, nets and drumlines were checked between 182 and 260 days a year, leaving hooked non-target animals such as rays and turtles to endure prolonged stress, injury or even death before contractors arrive. Now, the Queensland Shark Management Plan 2025–2029 has announced that all nets and drumlines equipment will be checked and rebaited daily, weather permitting.

In recent years, the hidden toll of shark control programs has come sharply into view as scientists, swimmers and concerned community members armed with drones and cameras have gathered alarming images of what was once invisible. It’s a reality captured in the feature-length documentary Envoy: Shark Cull, directed and produced by filmmaker Andre Borell, co-founder of environment-focused conservation organisation Envoy Foundation.

“Once people see what’s happening below the surface, they can’t unsee it,” Andre says. “This isn’t a safety program. It’s a taxpayer-funded culling program that has immense resources spent on sanitising its image.” After its release in 2021, the film’s images sparked outrage, policy debate and a growing call for change.

Among the many critics of shark nets is marine biologist Holly Richmond, director of another damning documentary, The Shark Net Film (2019). She recalls her first encounter with a tiger shark, a species she’d always dreamed of seeing in the wild. “It took my breath away, but not in the way I’d imagined,” she says. “Reality hit hard as I watched this beautiful tiger shark fight her final battle, hanging hooked on a baited drumline. Killed out of fear – a tragic waste of an innocent, misunderstood animal.” It’s just one of many such encounters Holly has had.

Politics and pop culture

It seems fear has, for decades, held these nets in place. They’ve become woven into Australia’s beach life by politics and pop culture. That narrative began more than a century ago when a handful of shark incidents at Sydney beaches ignited community panic and pressure for political action.

The response was galvanised by the Shark Menace Advisory Committee leading, in 1937, to the launch of the world’s largest shark control program – a series of large mesh nets set off popular NSW swimming areas. Queensland followed in 1962 with a statewide program that still operates today. At the time the logic seemed simple: fewer sharks would mean fewer attacks. And nets, it was believed, would mean fewer sharks.

Then came Jaws. Steven Spielberg’s 1975 blockbuster movie, inspired by Peter Benchley’s novel of the same name, turned a misunderstood apex predator into a cinematic monster. Overnight, sharks became public enemy number one – the perfect villain for a sunburnt country obsessed with the sea. Benchley himself would later spend the rest of his life trying to undo the myth his story helped create. Decades on, it’s time to turn to the statistics to see if that fear of being ‘bitten’ in fact holds up to reality.

Many Australians would be comforted to know our country isn’t the shark-bite capital of the world. That title belongs to the United States, where Florida consistently records the highest number of human–shark interactions globally.

In 2024, the International Shark Attack File recorded 28 shark incidents (only one fatal) in the US, accounting for about 60 per cent of confirmed shark incidents worldwide. Australia recorded just nine, well below our five-year annual average of 15 – and none were fatal. Tragically, that changed in 2025, when five fatal incidents (as of 12 December) occurred along our beaches.

The Australian Shark-Incident Database (formerly the Australian Shark Attack File), managed by Taronga Conservation Society, acknowledged in a recent report that, in the past decade, there were on average 2.8 fatal shark bites each year in Australia. In 2023 there were four fatalities – but, to put this into context, 1266 people died on Australian roads that same year, and Surf Life Saving Australia recorded 125 coastal drownings during the 2022–23 financial year.

Statistically, sharks barely register as a threat. In Australia the odds of being killed by a shark are about one in 8 million, yet public reaction and media coverage remain hugely disproportionate.

Australia’s reputation as “the continent where everything can kill you” has become a running joke online. International headlines love to remind us that just about everything here bites, stings or slithers. In reality, you’re far more likely to die walking across the street or driving in your car.

Still, our love affair with the ocean shows no sign of slowing down. Surf Life Saving Australia’s 2024 National Coastal Safety Report found that: “In the last 12 months, 16.6 million Australian adults (16 years and above) visited the coast on average 3.3 times each month. This suggests that there were over 650 million individual visitations to our coast last year.” With so many bodies in the water, some shark encounters are inevitable.

Anecdotally, surfers report seeing more sharks than ever. However, the conditions that shape sightings and the number of encounters aren’t just because more people are in the water.

Leading Australian shark researcher Associate Professor Charlie Huveneers, of Flinders University’s Southern Shark Ecology Group, says: “Shark-bite numbers are slowly increasing globally, however the reason for this increase is difficult to pin down as many factors can contribute to the observed trends in shark bites.”

In the 2025 paper Global systematic review of the factors influencing shark bites, Charlie and his colleagues identified 40 factors that can affect shark-bite risk. “Human population growth, habitat modification and destruction, declining water quality, climate change and anomalous weather patterns, and changes to the distribution and abundance of sharks and their prey are all often proposed to explain the recent increases in shark bites,” Charlie says.

“However, the infrequent occurrence of such events reduces our ability to determine which of these factors explain the increase in shark bites the most. It’s unlikely that any of these factors on their own can explain the increase we’ve seen over the last decade.”

Huge bycatch

Despite decades of use at a cost of millions, there’s still no sound scientific evidence that nets or baited drumlines reduce shark-bite risk. Charlie and his colleagues also reported on the efficacy of mitigation measures used in Australia and found that “there were no statistical differences in the number of shark bites (including both fatal and non-fatal) between beaches with shark nets and those without” and that “while area-based protection can reduce shark-human interactions, a combination of measures, including education and personal protection, would be more efficient”.

The bycatch of shark nets is significant. Of Queensland’s program, Sea Shepherd Australia found: “Catch-data dating back to November 1962 reveals that over 84,800 marine animals have been ensnared in the program, including many vulnerable, endangered and critically endangered species” – from dolphins to sea turtles – since the 1960s.

“These animals die a long, slow and torturous death. You wouldn’t wish that on your worst enemy, let alone Australian wildlife,” says Lawrence Chlebeck, Humane World for Animals Australia marine program manager. “The loss extends beyond ethics. People pay to see these species alive, diving with grey nurse sharks, swimming with turtles or whale watching, so it’s madness to keep killing them for protection.”

A 2024 evaluation by KPMG of Queensland’s shark control program noted that this level of mortality is no longer acceptable to many Queenslanders and there is a need to reduce the impact on ecosystems and respond to community expectations. Shark populations also play a vital role in regulating prey numbers and maintaining the balance of reef and fish communities. “It’s like pulling threads from a tapestry – when sharks disappear, the whole system begins to fray,” Leonardo explains.

Studies by a series of experts, including Dr Carl Meyer from the Shark and Reef Research lab at Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, reveal that culling large predators such as tiger sharks can even increase the risk of encounters with people, by allowing smaller, inexperienced juvenile sharks into an area. These ‘teenagers’ are more unpredictable and more likely to ‘investigate’ humans.

“Removing a single shark doesn’t reduce risk as that shark may never have bitten anyone. To meaningfully change risk, we’d likely need to kill large numbers of sharks, but we don’t know how many,” Charlie says. “So, the real question is: should we invest in measures that can be lethal to non-target shark and other species, and might have limited effects on the number of shark bites – for example as seen in Hawaii – when non-lethal methods can be equally if not more effective without the environmental cost?”

Shark nets may make beaches more dangerous for other reasons, too. “When animals are trapped in shark nets, their struggle emits low-frequency sounds underwater that can attract sharks who are in the area. When this happens, shark nets are ringing the dinner bell,” explains Associate Professor Chris Pepin-Neff, from The University of Sydney, who completed the world’s first PhD on the politics of shark attacks, and authored the book Flaws: Shark Bites and Emotional Public Policymaking.

Photographs obtained through Freedom of Information requests by Envoy Foundation from the NSW Government support this point. One shows a bull shark caught in a net, its body marked with fresh bite wounds from larger sharks. “It is evidence of how bycatch can literally become bait,” Chris says.

Power of fear

If the science is clear, why do shark nets still hang along our coasts? The answer seems to lie less in ecology and more in politics. Fear is powerful currency, and it appears that no minister wants to be the one who removes the nets and is seen to be responsible for the next shark-bite headline.

Chris authored a paper, entitled Australian Beach Safety and the Politics of Shark Attacks, that described the politics of shark attacks as a case of “survival of the fittest problem definition”. Chris explains: “If a problem can be easily understood and the solution is familiar and affordable, then it does not need to ‘work’ in order to be politically valuable.

Governments invest in what can be seen: buoys, nets, drumlines and drones. And sometimes things like drones are effective, but using policies to advance the ‘theatre of safety’ is real. These measures look protective, but their real function is political – to calm the crowd. Politicians don’t believe that shark nets protect beaches; it is that it protects them at the next election.”

But politics is only one half of the equation. The other is the media. Media coverage amplifies this cycle, turning rare events into headline dramas that reinforce any potential threat. “If it bleeds, it leads,” Lawrence says. “The weight and volume of media reporting on shark incidents is completely disproportionate; it builds risk in our psyche that makes shark bites seem far more frequent than they really are, fuelling fear and political self-preservation that keeps lethal shark programs alive.”

In 2025, after years of lobbying, the NSW Government began planning a trial to remove shark nets from three beaches, the most significant policy shift since the 1980s. Before it began, tragedy struck. There was a fatal attack on an experienced surfer at Long Reef Beach, in Sydney’s north. It reignited debate about shark nets and stalled the reform. The setback highlighted how easily reform can be derailed, even when the evidence supports it.

What’s less known is that a legal loophole allows governments to keep these outdated programs running indefinitely. Under Section 43B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), activities that pre-date the law’s commencement date can continue indefinitely without modern assessment.

“In effect, if you were killing protected species legally before 1999, you can keep doing it. No new permits. No federal scrutiny,” Andre says. “It would be like letting a company that once hunted whales keep doing so today because it was ‘grandfathered in’.”

Non-lethal controls

A new approach to ocean safety is rapidly building across Australia, challenging the belief that nets, baited hooks and culling is acceptable. It’s grounded in coexistence rather than control.

Worldwide, many countries are moving away from lethal control. South Africa, once reliant on shark culls, is transitioning towards non-lethal deterrents, while Brazil tags and relocates many of its sharks offshore.

Western Australia famously scrapped its shark culling program in 2014 after a culling trial sparked public outrage, replacing it with tracking, real-time alerts, education and drone surveillance.

The new Queensland Shark Management Plan 2025–2029 directs most of its $88 million budget to non-lethal measures, including whale-deterrent research and rescue teams. Its four-year SharkSmart drone trial proved that drones, which pose no risk to wildlife, can spot as many sharks as traditional gear while operating for far less time, and also aid swimmer search-and-rescue efforts.

NSW is taking a similar approach with drones, education programs, listening stations and non-lethal SMART (Shark Management Alert in Real Time) drumlines that allow sharks to be tagged, tracked and released alive.

“They’re not without their flaws,” Leonardo says of the drumlines. “These devices still rely on baited hooks, which can attract sharks closer to shore, and if response times lag, capture stress can prove fatal. We should continue investing in technologies that don’t rely on catching sharks at all.”

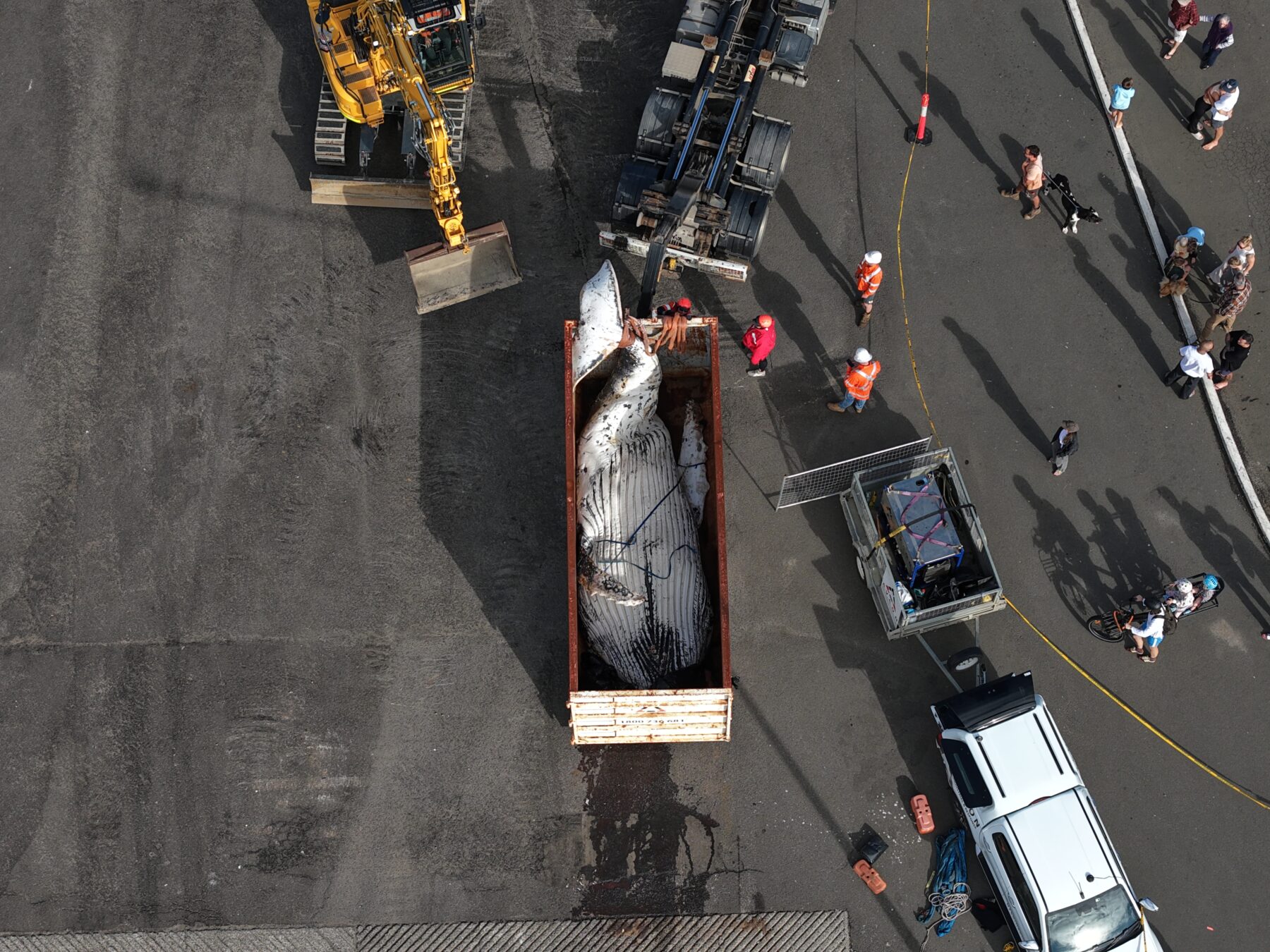

Despite major advances in non-lethal technology, NSW and Queensland still rely on lethal nets and drumlines. Queensland keeps its gear in the water year-round, while NSW rolls its nets out each spring, a timing increasingly questioned because it overlaps with peak humpback whale migration.

Surfer and photographer Shaun Petersen captured a series of confronting images of a juvenile humpback whale that drowned after becoming entangled in a shark net off Coledale, in NSW’s Illawarra region. All he could do was watch and document the moment, taking photographs as its lifeless body was loaded onto the back of a dump truck bound for landfill.

“I’ve always had a healthy respect for sharks. We all know the risks when we paddle out. They’ve got more right to be there than we do,” Shaun says. “Seeing that whale calf tangled and lifeless… it was gutting. I had to just watch, knowing that trying to free it could land me in jail. The law protects the net, not the animal. The very thing meant to keep us safe is killing what we love and attracting what it’s supposed to deter.”

His frustration isn’t misplaced. Under NSW law, anyone who tries to free a trapped animal risks prosecution for tampering with “safety equipment”. It’s a tension that underscores the gap between community sentiment and government policy.

Queensland still defends the use of its nets. “Until the new technology is as effective at protecting beachgoers as the old, we will continue to invest in what keeps Queenslanders and our beaches safe,” said Queensland Minister for Primary Industries, Tony Perrett, in a prepared statement. “Unlike our southern neighbours, our beaches remain hugely popular throughout winter, and we won’t compromise on swimmer safety.”

This is despite the Local Government Association of Queensland recently passing a landmark motion calling on the state government to trial non-lethal, evidence-based shark mitigation measures during the whale migration season. The vote was loud and clear: 204 councils in favour and only seven opposed.

For communities seeking a physical in-water barrier, the SharkSafe Barrier offers a humane, science-driven alternative. Developed in partnership with Stellenbosch University in South Africa, the system uses a seabed-anchored, flexible barrier with ceramic magnets incorporated that mimic a natural kelp forest. This creates a magnetic ‘wall’ that overwhelms sharks’ electro-sensory organs, repelling them without harm while allowing other marine life and boats to pass through freely.

Once established, the barrier forms an artificial reef, thereby enhancing local biodiversity. Scientific trials in South Africa and the Bahamas have shown 100 per cent effectiveness in deterring large target species such as great white, tiger and bull sharks.

“It’s the first nature-inspired, eco-friendly, shark-specific barrier designed to protect people and sharks, significantly reducing the risk of shark-human encounters while contributing to marine biodiversity,” says Neill Laurenson, director of SharkSafe Barrier.

The reality of risk

Risk is a part of entering the ocean. Few people understand this more than shark-attack survivor Dave Pearson, who was bitten by a three-metre-long bull shark off Crowdy Head, NSW, in 2011. The encounter left him with deep physical and emotional scars, but also a deeper understanding of the ocean. Dave later founded Bite Club, a global support network for survivors of encounters with apex predators including sharks, crocodiles, lions and even hippos.

“People want someone to blame – anyone but themselves – rather than accepting the ocean is wild and risk is part of entering it,” Dave says. “When I paddle out, the responsibility is on me. And am I prepared to take it? I love the ocean. A healthy ocean involves all species. It’s my job to make sure I’ve done everything I can before I go out: check the water clarity, the weather, and fish activity. I even fly my drone if I’m surfing a remote area to check.”

WA has led the way with a shark-deterrent rebate program that helps people buy approved devices, including Australian-made electric repellents that can cut bite risk by up to 60 per cent. Bite-resistant wetsuits made from puncture-proof fibres offer added protection by reducing injury severity.

But experts agree long-term coexistence relies more on education than control, encouraging safer personal behaviour. This shift is growing nationwide, driven by groups such as the Envoy Foundation’s #NetsOutNow campaign, which is helping move public attitudes from fear to understanding and promoting modern, humane alternatives to outdated shark-control methods. “The data is showing unity, not division, and it’s time our policies reflected that and respected the intelligence of the Australian public,” Andre says.

A national YouGov and University of Sydney survey, co-funded by the Envoy Foundation, found most Australians know the ocean cannot be 100 per cent safe, and they don’t expect governments to do the impossible. That acceptance transcends politics: 79 per cent of Labor voters, 87 per cent of Coalition voters and 93 per cent of Greens voters agree absolute safety is impossible.

But education and public support can only go so far if the laws themselves remain unchanged. “The biggest opportunity is for legislative change at the federal level by removing exemptions in the federal environment law for state shark programs,” Andre says. “This reform would be the first major change to the EPBC Act in 25 years [and] would subject these programs to proper assessment and permitting, which they currently bypass.” The reform has so far been unsuccessful.

In 2019, Humane Society International – now Humane World for Animals – successfully challenged Queensland’s use of lethal baited drumlines in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, arguing they offered no proven safety benefit. The Administrative Appeals Tribunal and later the Federal Court ruled in Humane World’s favour, ordering that sharks could only be killed as a last resort, setting a national precedent for non-lethal shark management.

“They’re not listening – not to councils, not to scientists, not even to the communities they’re supposed to serve,” Lawrence says. “The only thing left may be legal action. We’ve already taken the government to court once and won, and we’ll do it again if that’s what it takes.”

After almost a century of shark-control programs, the picture is now clearer than ever. Nets and drumlines introduced in the 1930s sit increasingly at odds with modern science, emerging technologies and a public that recognises the ocean can’t be made risk-free.

Australia has everything it needs to move beyond legacy measures towards approaches that reflect what we now know. The real question is whether our decisions will finally align with science.