The sky was clear, but the ground beneath Anna Nicholas was sodden, chewed into a slurry by the boots of hikers trekking through days of rain. It was her third day on the South Coast Track – a remote 85km wilderness traverse through Tasmania’s Southwest National Park. Anna and her two walking companions, Claire Cook and Claire Hynes, had been trudging for more than six hours through thick, ankle-deep mud, packs heavy on their backs. An overnight camp location – at Osmiridium Beach – was finally within reach.

Surrounded by buttongrass and a tangle of gnarly coastal scrub, Anna suddenly pitched forward. “I don’t even think I really tripped over anything in particular,” she recalls. “But I fell forward onto a branch that went straight across my eyes.” The impact was instant and visceral, the weight of her pack keeping her down. “My eyes got pressed back so hard I thought that I actually wasn’t going to have any eyes when I opened them.”

She stayed on all fours, stunned. “Just leave me for a minute,” she told her friends. “I felt really nauseous. Headache. I went to sit up, wanted to vomit and faint, so I had to lie back down.”

Anna had suffered lacerations around both eyes and – being a nurse in her day job – she guessed she was concussed. “I just got this overwhelming feeling of ‘thank God I’m okay’,” she says. “I looked at my friends and said, ‘I think I’m really lucky – we need to get out of here.’”

She activated her satellite device, which allowed her to message her husband directly and coordinate with emergency services – a decision that would see the distinctive red Westpac rescue helicopter hovering above the group within the hour.

Anna stayed where she’d fallen while paramedics made their way in on foot. “We were waving like crazy,” she says of the moment they spotted the incoming chopper. Rob Brittle, the attending paramedic, shouldered her pack and walked with the group for the final stretch to the chopper on the beach. “He was just amazing – so calm,” Anna recalls. “It was all just smooth sailing. So easy.”

She also remembers how the rescue team went out of their way to ensure all three women could fly out together. “That was the icing on the cake for everyone,” Anna says. “I would have been so worried about them.”

Despite the remoteness of the location in a wild corner of southern Tasmania, 30km from the nearest road, Anna’s rescue operation had unfolded with slick efficiency, and she was soon reunited with her family at the Emergency Department of the Royal Hobart Hospital.

With more than 15 years’ paramedicine experience – including five spent in the rescue helicopter – Anna’s paramedic that day, Rob, is part of a specialist team trained to respond to emergencies in Tasmania’s most remote and challenging environments. His background in outdoor guiding and ski patrol, along with field training in Antarctica, gives him an edge in difficult terrain.

From major traumas to walkers who’ve simply had enough, Rob has seen every kind of call-out. Each job, he explains, involves rapid decision-making and evaluation: “We fly to the GPS location, then do a site assessment – terrain, wind, slope, surface, visibility. We decide: can we land? Can we hover and step out? Or do we have to winch? Winching is the last resort. It’s the riskiest option – for us and the patient.”

Small mistakes matter

In the bush, small miscalculations add up. A delayed start, a misjudged forecast, key equipment left behind – for the volunteers and professionals who respond, these are familiar patterns that show up.

“There’s the late-day underestimation,” says Ben Arthur, a volunteer with Tasmania’s SES Search and Rescue unit. “People start walks thinking it’ll be quick – then the weather turns, or the terrain’s tougher than expected. They don’t have much contingency.”

Ben works with CSIRO, helping to manage Australia’s national research vessel, the Investigator. When a rescue call comes in, he often leaves work to respond. “I’ll get a message and duck out from work,” he says. “They [his employer] are really supportive – especially when they know someone’s missing.”

Since joining the SES six years ago on the recommendation of a bushwalking buddy, Ben has attended call-outs ranging from lost hikers on kunanyi/Mt Wellington to a high-profile multi-day search for a missing child on the Tasman Peninsula. During that time, he has noticed recurring patterns: walkers overestimating their ability, setting out too late, or tackling challenging terrain without adequate gear.

“You don’t need a full survival kit,” Ben says, “but you do need a plan if things go wrong.” Tourists, he adds, are particularly prone to sticking to itineraries despite changing conditions. “As locals, we know to wait out the weather. But visitors often don’t have that option.”

Rob sees similar patterns from the air. “They skip the ‘apprenticeship’,” he says. “They see something online and head straight there. They don’t build up experience. And because weather forecasts are so good now, they might leave behind essential gear, thinking they won’t need it.”

Some misadventures, however, really leave the professionals shaking their heads. “We once rescued someone off the Three Capes Track who’d activated their PLB [personal locator beacon] because they just didn’t want to be there anymore,” Rob says. “We flew them out and they walked straight into the airport and flew home.”

Rob is quick to add, however, that all beacon activations are treated seriously, and points out that individuals have different thresholds for what they consider an emergency. “Someone might be very hungry and a day away from food and think that’s an emergency,” he says. “Someone else breaks a bone and keeps walking. For us, it’s not about judging. We just respond. But there is a lot of room for better education.”

Satellite response

Anna’s rescue on the South Coast Track was one of between 1200 and 1500 emergency beacon activations each year within Australia’s search and rescue (SAR) region – an area spanning 52.8 million sq.km, or about one-tenth of the earth’s surface. From the Red Centre to Antarctica, across the Southern and Indian oceans, and out into the Pacific, Australia’s SAR system is vast, varied and collaborative.

When someone sets off a distress beacon, the signal is detected by an international satellite network and relayed to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), which coordinates land, aviation and maritime rescues nationally from its headquarters in Canberra. At any given time, aircraft are searching open oceans and hovering over remote bushland. On the ground and at sea, crews are tracking through rugged terrain, guiding winches, and navigating rough waters – all part of a SAR network linked by satellites and a web of agencies that rarely rests.

In just one month in early 2025, SAR teams retrieved 11 hikers from steep terrain in Morton National Park on the New South Wales South Coast, winched a young couple from a washed-out 4WD track near Cape Melville in Far North Queensland, airlifted a kayaker bogged in mud south-west of Melbourne, and plucked two injured climbers from a narrow ledge on Belougery Split Rock in Warrumbungle National Park, in north-west NSW.

“We receive all 406 MHz distress alerts in the Australian search and rescue region,” explains former naval officer Ben Flight, AMSA’s principal advisor for integrated operations. “It’s a huge patch – land, sea, remote islands, Antarctica.” From there, AMSA determines what kind of emergency it is – a yacht in trouble, a lost hiker, or a solo rower adrift – and which agency is best placed to respond. “We triage around 20 alerts a day,” Ben says. “Most are false alarms, but a few a day require a response to be launched and coordinated.”

One of the more complex rescues Ben was directly involved in made national news in 2023: the recovery of the Spirit of Mateship, a racing yacht disabled in rough seas off the NSW coast east of Nowra. “We worked with Defence, NSW Police, and even used HMAS Canberra to create a windbreak so a police vessel could extract the couple,” he recalls.

Later that year, AMSA assisted in the international rescue of 24-year-old Tom Robinson, Australian Geographic’s 2024 Young Adventurer of the Year. Tom’s self-built rowboat had capsized in the Pacific near Vanuatu during the final leg of his trans-oceanic crossing. He was rescued by a cruise ship after clinging to his overturned vessel for 14 hours.

Even the most experienced adventurers can get caught out. “There’s often no single mistake – just a series of small decisions or bad luck,” Rob says. “We’re not there to judge. We’re there to get them home. People should expect excellent emergency services – not just in the city, but in the bush too. That’s our job.”

Australia’s SAR system is built on that ethos: a network of professionals and volunteers – state police, paramedics, doctors, AMSA staff, rescue pilots and community responders – united by a single goal.

Back in the remote wilds of southern Tasmania, in November 2024, that unity was again brought to the fore in a rescue that pushed both people and systems to their limits.

Remarkable rescue

It was one of the most extraordinary rescues Rob had ever been part of. “A kayaker trapped for 20 hours – hypothermic, needed an on-site amputation, went into cardiac arrest. We winched him out with mechanical CPR going. He ended up on ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oyxgenation, a life-support system that warms and oxygenates blood outside the body] in hospital – and went home with no lasting brain injury,” he says. “That’s world-class.”

The kayaker was 65-year-old Valdas Bieliauskas, a paddler from Lithuania who became pinned in the wild upper reaches of the Franklin River in Tasmania’s Franklin–Gordon Wild Rivers National Park. His leg was trapped in a submerged rock crevice at the Coruscades – a remote section of tight whitewater surrounded by dense temperate rainforest and towering dolerite. His party triggered an emergency beacon just before 3pm.

By 7.30pm, a helicopter had winched rescuers into the gorge – including paramedics, police and specialist swiftwater technicians. One of the swiftwater rescue technicians was Adrian Petrie, a senior station officer with the Tasmania Fire Service and volunteer with Surf Life Saving Tasmania. His swiftwater training was through the latter organisation after Tasmania’s 2016 flooding disaster revealed a skill gap in the state.

“We were winched in basically right over the scene,” Adrian says. It was the first time he’d ever been winched into a rescue scenario. “[Valdas] had been in the water since mid-arvo.”

More than 50km from the nearest road, communications were unreliable, with no phone reception and only patchy satellite signal. “We couldn’t get a message out,” Adrian says. “AMSA actually flew a plane over to orbit above us, acting as a relay.” The aircraft – AMSA’s Challengerjet, flown in from Melbourne – circled overhead, relaying critical messages between the team in the gorge, the helicopter crew, and AMSA’s Joint Rescue Coordination Centre in Canberra.

There’s often no single mistake – just a series of

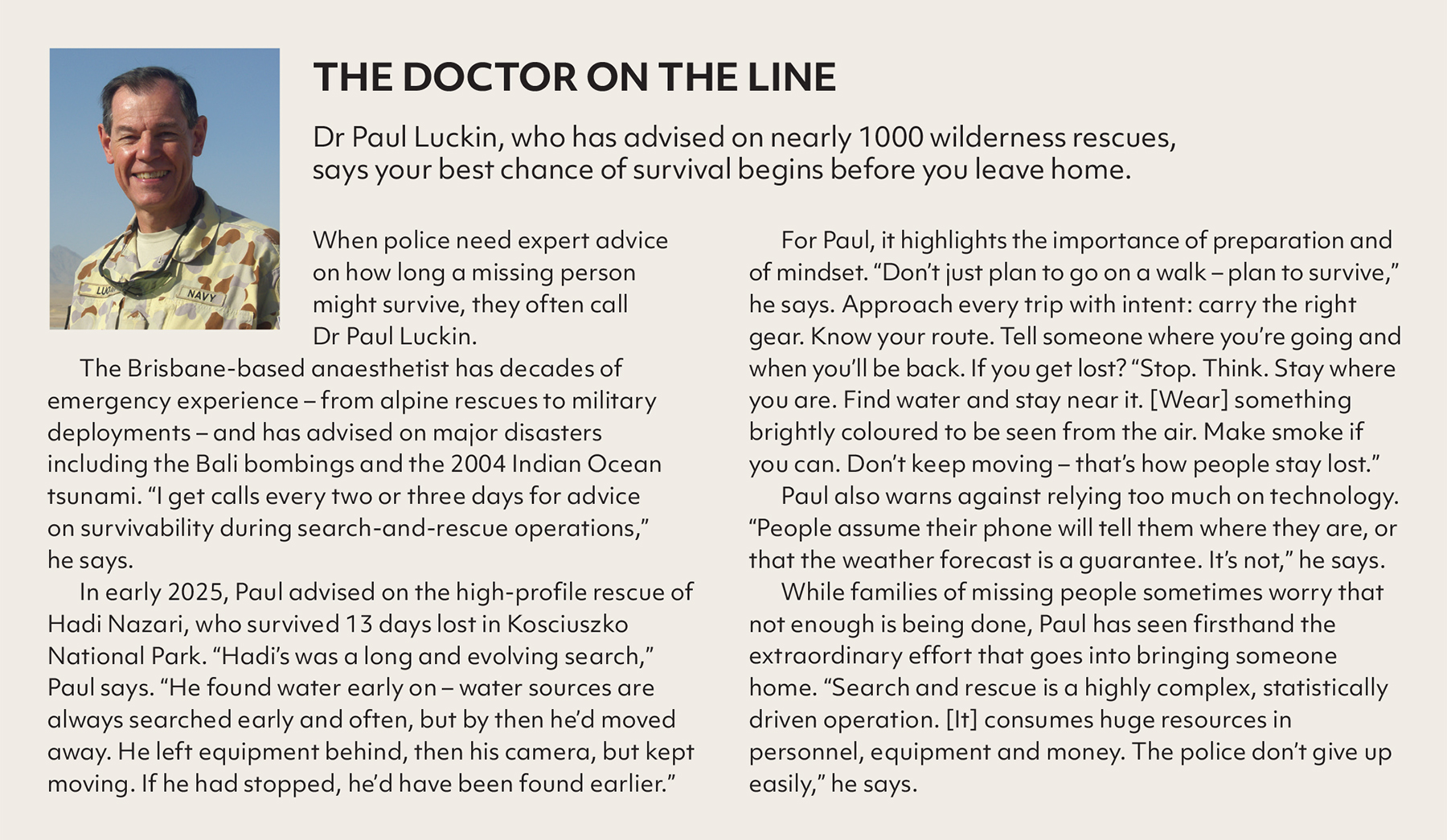

Paramedic Rob Brittle

small decisions or bad luck.

The team worked into the night trying to free him. “We tried slings and ropes to pull him out,” Adrian says. “Then hydraulic spreaders, a bottle jack, mini-airbags. We continued multiple rescue attempts over the next 14 hours – nothing worked.” The cold was taking its toll. “Shivering had stopped, speech was incoherent – classic hypothermia signs,” he says. “He wouldn’t have lasted another six hours.”

A second medical team was flown in to assist, and the decision was made to amputate – on-site, underwater, using a flexible wire saw known as a Gigli saw.

“Once he was sedated, the amputation took about 10 minutes,” Adrian says. Soon after, Valdas’s heart stopped and the team began CPR, then attached a mechanical device called a LUCAS (Lund University Cardiopulmonary Assist System) to continue compressions before winching him into the air for the 50-minute helicopter flight to the Royal Hobart Hospital.

Against the odds, Valdas was successfully treated and survived. “It worked because of that collaboration,” Adrian says. “Fire, police, surf lifesaving, paramedics and doctors – no egos. Just respect for each other’s skills.”

Life and death

The Franklin River incident was a rare, high-stakes operation – but in any remote emergency, the right gear, experience and preparation can mean the difference between life and death.

Ben Flight encourages adventurers to choose an emergency beacon that suits their activity. “Traditional PLBs [personal locator beacons] are great – robust, waterproof, simple. But satellite emergency notification devices allow for two-way communication, which can help us understand the situation better. Just make sure your device is registered, fully charged, and that you know how to use it.”

Rob agrees, and suggests a simple mantra in the case of emergency: “Stop. Stabilise. Advertise. Stop where you are. Stabilise – set up your tent, get warm, eat and drink. Then advertise – call for help or activate your beacon.”

Offline mapping apps like Gaia GPS or Avenza Maps are also helpful to avoid getting lost, but only if you download the maps in advance – something, Rob has found, not everyone considers in advance when heading into remote, out-of-range areas. Printed topographic maps and a compass still also have a role to play.

As for Anna, she has fully recovered and says of her brush with misadventure that she wouldn’t do anything differently. “We were 100 per cent prepared. I had the Garmin. My friend also had an EPIRB [emergency position indication radio beacon]. We had all the gear. It was just a fluke accident.”

Her only lingering emotion, beyond gratitude, was a quiet fear that she had burdened the system. But the rescue team quickly dispelled that. “They said, ‘This is why we do this. So you can go out and enjoy your life – and know that help is there if something happens.’ That meant a lot.”

The reality is, after all, that misadventure is part of adventuring. We head into wild places precisely because they’re unpredictable. And while preparation and experience matter, so too does the deeper knowledge that if something does go wrong, every effort will be made to find you and bring you home. That reassurance, and the commitment behind it, is what allows many of us to keep seeking the edge.

“We’re lucky in Australia to have such a strong emergency response system,” Ben Arthur says. “People get lost or injured – it happens. But we’ve chosen, as a country, to support those people. That’s something we should be proud of.”