Dick Smith grins as though he’s getting away with something. “Towing the iceberg into Sydney Harbour, jumping the double-decker bus – that’s the stuff,” he recalls. “I’d be quite happy to be remembered as an Aussie larrikin.” The word lands with the easy authority of a man who’s made a life out of audacity – sometimes mischievous, sometimes mortal, always purposeful.

The founder of Australian Geographic is now aged 81. But his spark for a life less ordinary – that energy and self-belief that compelled him to fly a helicopter across oceans and a balloon into the jet stream at 23,000ft – seems as strong as ever. He says his younger self didn’t believe he would die, and he talks about his brand of “responsible risk-taking” that often brushed the limits of possibility. “I can’t believe I’m alive,” he admits.

What held it all together and kept the show from tipping into chaos was a talent he details without much fanfare. “I’m good at getting good people,” Dick says simply.

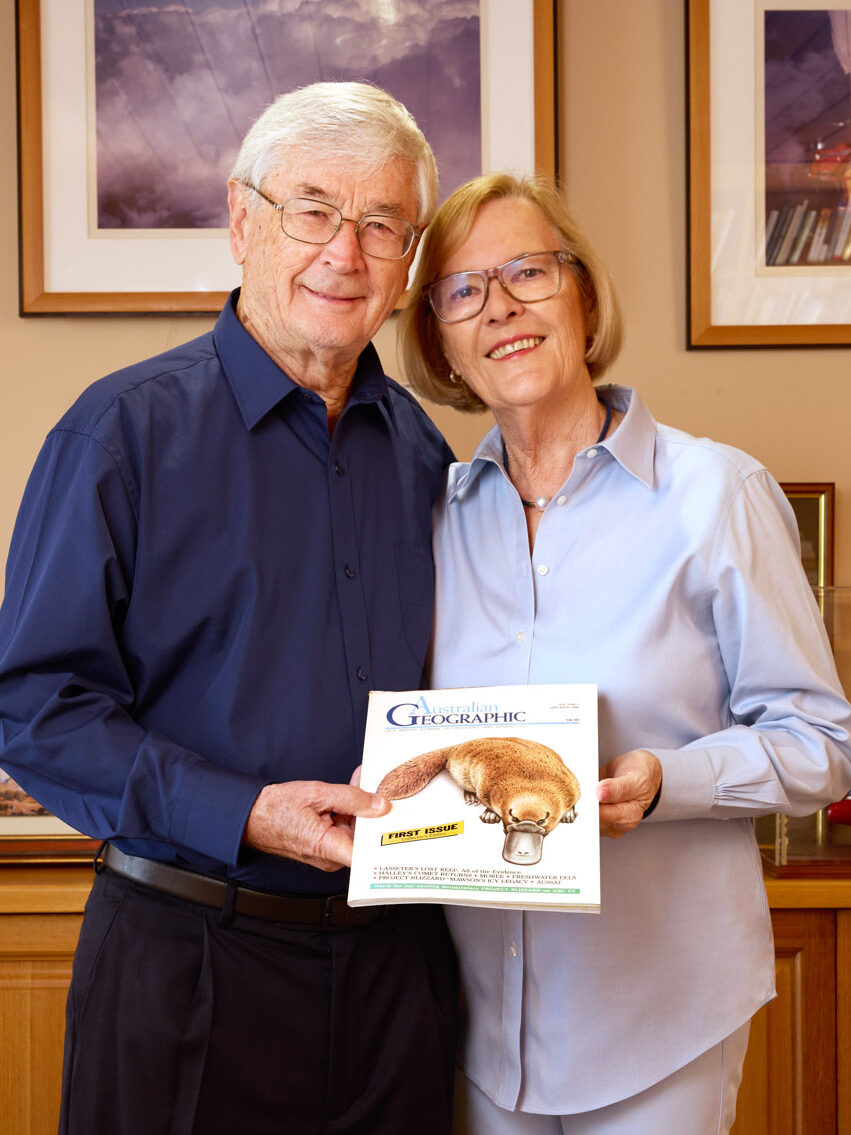

And then there’s Pip, always Pip. “I admire Pip for allowing me to do it,” he says. And he means the lot of it – the mad routes, the radical ideas, the stunts that made the six o’clock news. She never told him to slow down when they were young, not in the car and not in life, and somehow that small fact became a love story. They married early – he was 24, she was 19 – and had two daughters, Hayley and Jenny. They now have nine grandchildren.

If the larrikin was the headline act, what followed was a steadier, more intricate set list: a boy alone in the bush; a salesman with a soldering iron; a publisher who wanted to change what Australia read about itself; a campaigner who kept asking if a nation, like a household, ought to have a population plan; a philanthropist who decided early that money made more sense flowing out than piling up.

Dick grew up in Roseville Chase, where the scrub ran right down to Middle Harbour and a kid could vanish between school bell and sunset. His mother had one rule: be back by nightfall. He built a raft out of timber and floated across the water, a small expeditionary force propelled by curiosity. “Don’t worry,” he used to tell her. “I’ll always turn up.” Decades later, as he flew solo across the Atlantic in a helicopter, a television reporter asked his mother if she feared for him. “No,” she said. “He told me he would always turn up.”

His other early influence lived right across the road: Grandpa Harold Cazneaux, a pictorial photographer. Dick remembers standing beside his grandfather in his darkroom, watching his careful hands coax clouds from blank paper. It wasn’t just the taking of pictures that mattered, he learned, but the shaping of what they meant. If that’s not the DNA of a publisher, of a storyteller, what is?

Dick was a loner by temperament, and happiest when tinkering with old electronics, walking and making things. He had no qualifications, but would forge his own path. In 1968 he set up a business servicing and installing car radios, which grew into Dick Smith Electronics – the little shop that became a network of stores and a household name. He loved creating his business empire more than administering it.

Pip was never just in the background. At the electronics shop she kept the gears oiled, and later, when Australian Geographic arrived, she carried half the load – sorting through subscription coupons and cheques that came by the shoebox, reading appeals from adventurers and dreamers, nudging the right ones forward.

With success came philanthropy. Dick’s first donation was $10,000 to a muscular dystrophy researcher named Dr Tony Kidman (father to a young Nicole and Antonia). After that, the giving never really stopped. He and Pip have now given away more than $85 million, with a personal aim to top $100 million. “We started with $610,” he says.

In the late 1990s he turned his entrepreneurial eye to food, launching Dick Smith Foods as an Australian-owned alternative to multinational brands. For more than a decade the label sold peanut butter, jams, biscuits and cereals – and channelled millions of dollars in profits into charitable causes.

Selling good news

Australian Geographic wasn’t born out of a business plan but a contrarian hunch. The media, he felt, had grown addicted to bad news and cheap sneers at country towns. “Surely this is a fantastic country,” he thought. “Surely we can talk positively about what’s happening here.” Friends warned him that good news doesn’t sell. He backed his gut – and borrowed a little of his childhood. As a boy he adored Walkabout, a first-person magazine that treated Australia with curiosity and respect. Why not build a modern version, a journal of record and wonder?

He surrounded himself with “capable people” and refused to apologise for a distinctive editorial creed: first-person, unabashedly positive, subjectively honest.

“I wanted writers who loved the place they were writing about,” he says. “We’d commission stories and send people out – sometimes risky, always expensive – and trust them to come back with the goods.”

They did, often magnificently: finding light in Moree where others had printed only shadow; sketching creatures that most of us had never heard of, much less seen; sending couples to test their mettle in the Kimberley, south-west Tasmania and Antarctica; standing guard over Mawson’s Huts as the ice closed in; and framing it all with maps so finely made they seemed to breathe on the page.

The first issue, published in January 1986, was a roaring success. Letters, cheques and order forms poured in, lifting the subscription list beyond 200,000 and turning a suburban post office into the unlikely frontline of a publishing phenomenon. “We never expected that,” he says. “It was supposed to run five years. Forty years on, it’s still here.”

He takes quiet pleasure in the word ‘journal’; so do many of those who grew up with it. It felt like a community, a bespoke universe of stories that trusted readers to keep faith with wonder.

The journal did more than publish. It funded research, expeditions and conservation – millions of dollars over the years – and lent its masthead to public health campaigns with real bite. Dick recalls the decision to take a stand against cigarette advertising directed at teenage girls. Australian Geographic paid to run ads calling out the culprits by name, and he believes that pressure helped push towards a national ban. It’s one of the things he’s most proud of.

The same stubborn optimism animated the journal’s stance on living “in balance”, a theme he has carried into public debates about growth and sustainability. The journal also became a springboard for his documentaries, which aired nationally and often challenged viewers to think about population, sustainability and risk. From aviation history to survival in the outback, the films carried the same mix of spectacle and conviction that defined Dick’s publishing work.

If there’s a single piece of counsel he offers the journal’s custodians today, it’s to send people who care to places that matter and ask them to write with their whole heart. In a digital world where everything seems to be free and opinions are manufactured by the minute, that sounds almost radical.

Adventurous antics

Dick’s adventures captivated Australia. In 1983 he completed the first solo helicopter flight around the world, and the first helicopter flight to the North Pole in 1987. He crossed Australia in a balloon in 1993 and the Tasman Sea in 2000 – at the mercy of the winds. He speaks about it not with swagger but with gratitude. “The weather could have killed me,” he says. “It always turned out to be okay in the end.”

He couldn’t have had these adventures without Pip’s support and know-how. She often went with him – sliding border-crossing documents across foreign desks, recording whole circumnavigations through the lens of her camera. When she couldn’t be in the cockpit, she was on the ground, sometimes alone in a snowed-in town, hunting down parts and heaters while Dick pressed on towards the North Pole. She organised the logistics of Dick’s adventures, creating order out of the chaos of travel.

Dick often tips his hat to the early aviators – Charles Kingsford Smith and Bert Hinkler among them – the lodestars of an age when long-distance flight was still a daring feat. He says five circumnavigations of the globe – in helicopter and fixed-wing aircraft – felt like the right number. The proposed sixth, to circumnavigate the globe wholly south of the equator, never left the map.

“If you keep pushing it, the risk will catch up with you,” he says, and in that single sentence, the boy who always turned up becomes a man counting his blessings.

Family support

The family portrait is noisy with life. Pip – who Dick met through Rovers and Guides when she was 17 – has been the ballast and the breeze. Dick says she handled sudden wealth with simplicity and generosity, steering the philanthropic course with him. She’s the one who cheered him on when ideas were still fragile and who, years later, said gently that a sixth lap around the world was one adventure too far.

Pip says she was a shy girl when they met, and that Dick had her abseiling down the Three Sisters before she’d caught her breath. He pushed newspapers into her hands and made her argue the headlines back to him, training confidence as a muscle. At Australian Geographic she found her voice – suggesting ideas, listening to the photographers who taught her light and shadow. When they drove around the world, she became the archivist, framing their days with her camera. “We’re a great team,” she tells me, and you believe it: the drive and the steadiness, the spark and the ground, each incomplete without the other.

Hayley and Jenny live not far – Sydney’s Avalon and the New South Wales Central Coast’s Ourimbah – which means there are dinners and drop-ins and nine grandchildren weaving memories into the weeks.

Dick talks about his grandkids with the unguarded joy of a man who’s had his share of second chances. They don’t read magazines much, he notes wryly, and they don’t watch documentaries either. The media future worries him, as it does anyone who cares about attention and truth. But the kids themselves – healthy, curious, sturdy – give him hope.

Ask what brings him the greatest personal satisfaction across the whole range of work, and he doesn’t hesitate. It’s family: to still be alongside the same partner, to get along with his daughters, to watch grandchildren find their place. He says Australians born in the 1940s won “the lottery of life”, but he means it in a way that’s less about becoming complacent with what they have, and more about staying accountable for what they can still provide.

If you’re Dick Smith, that means trying to widen the circle. You back teachers and scientists. You fund rescue services and research. You advocate for Indigenous reconciliation and against big tobacco. You give the money away while you’re here to see the good it does.

Return to home

Towards the end of our conversation we circle back to the big questions. Why did the journal work? Why did his little electronics shop turn national? Why did so many of his adventures succeed?

He returns, again, to people. “Surround yourself with capable people,” he says. “My success has come from that.” Then he points, almost cheerfully, at limits. “We can’t grow forever. We should live in balance.” In his voice, the words sound less like a policy pitch and more like the distilled ethic of a long marriage, a long career, and a long look at a continent that’s harsh, and fragile, and generously alive.

When I leave, I think about the word he has chosen for his epitaph – larrikin – as the framework for understanding the builder, the pilot, the publisher, the giver. The problem is, people don’t take larrikins seriously, so Dick Smith’s answer, for more than half a century, has been to let his work speak for itself. The bus landed successfully. The balloon found the coast. The journal arrived in 220,000 homes and told us our own stories with care. The family stayed close. He always turned up.

And that, in the end, is the larrikin’s best trick: not the jump or the headline, but the steady return – to home, to country, to the people who made the risk worth taking.